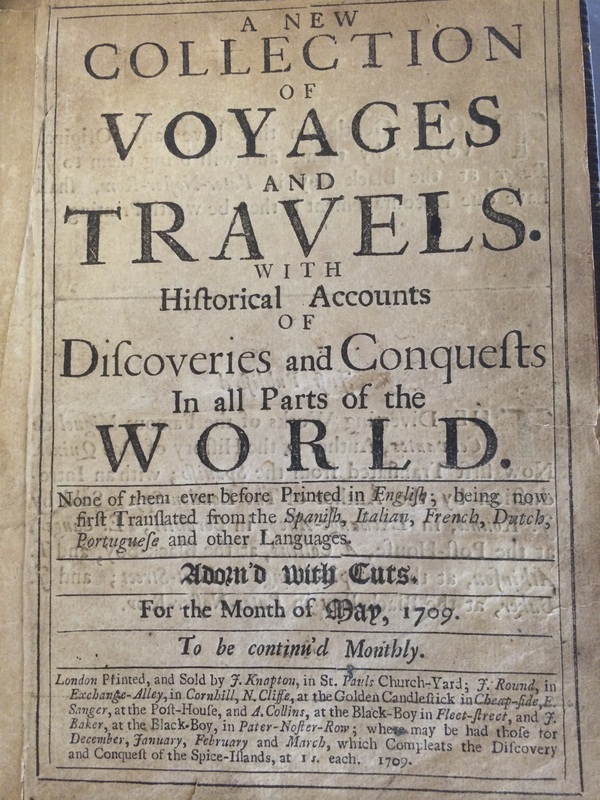

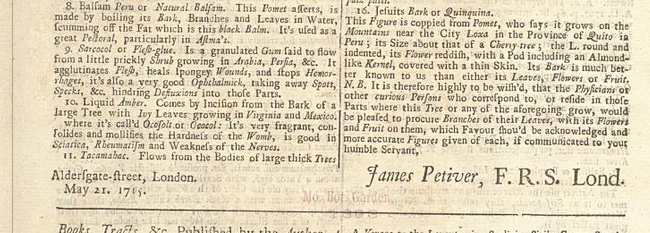

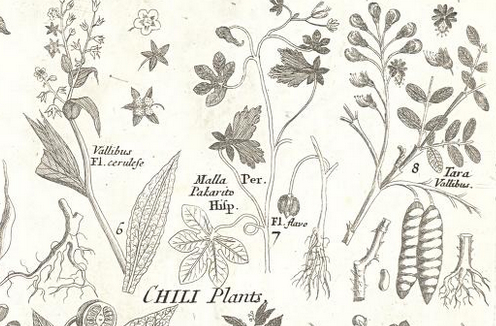

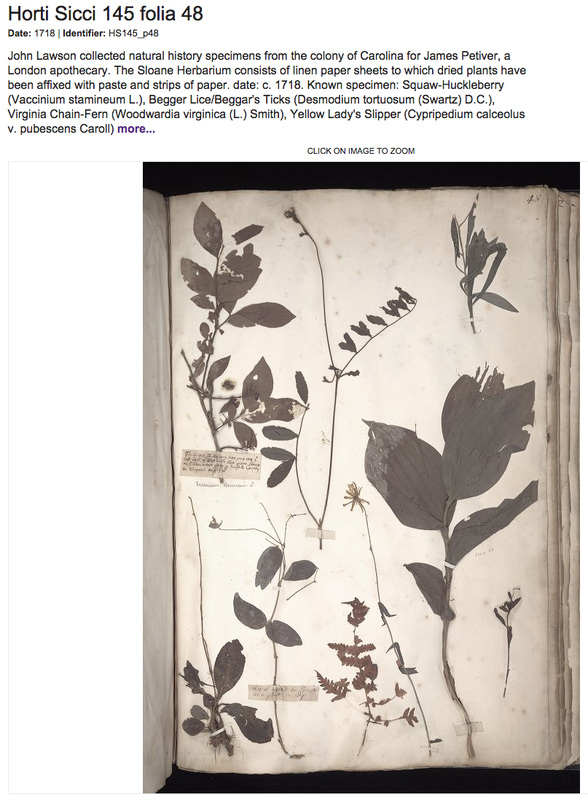

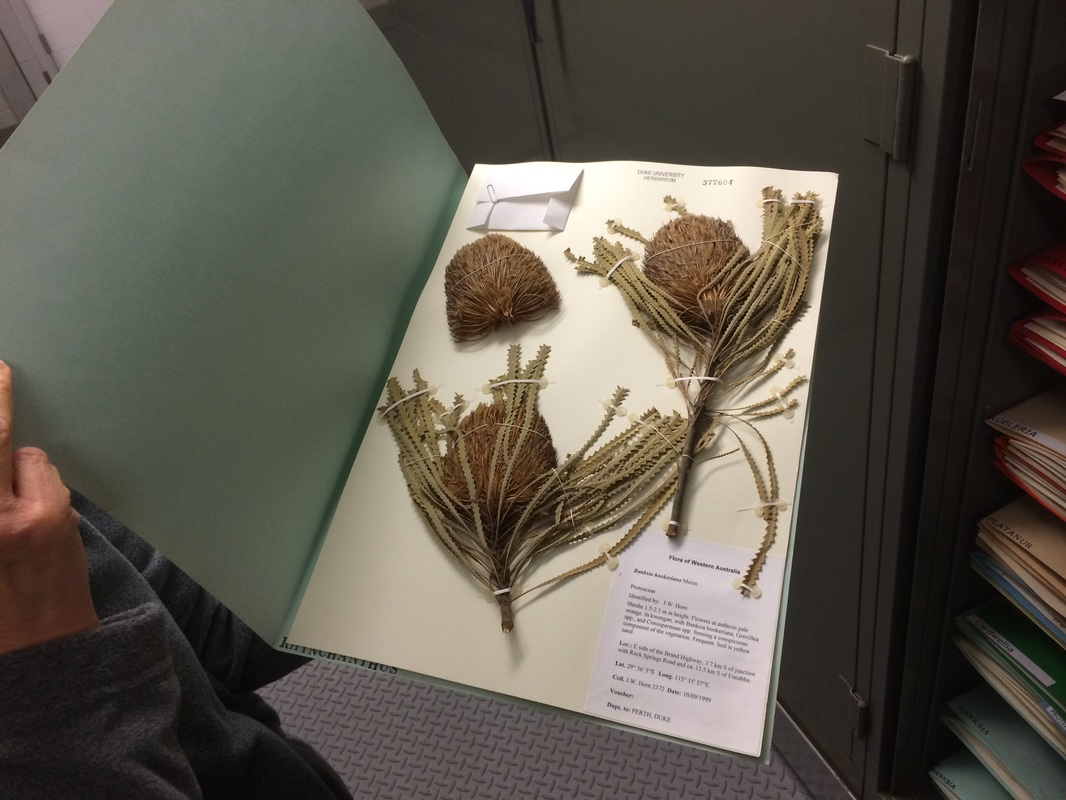

| Anyhow, Lawson's work did great in the anthology and was eventually printed, we know, as A New Voyage to Carolina, with all its attendant histories and a single page of weird drawings and all the rest. Another thing I'm jealous of, though, is that Lawson had going for him that nobody knew anything about his territory. Carolina was pretty big news if you were a London gentleman hanging around a coffee shop with time on your hands. Not so much now -- I'm rediscovering everything I find. If occasionally I cast a bit of new light on something that's fine, but it's like Ecclesiastes says -- there's nothing new under the sun. Given which, thank goodness for little kids. As I mentioned, to see some of the botanical specimens Lawson gathered, I'm going to England, to the Natural History Museum, where they remain. But speaking of new discoveries, my wife, June, and I will be taking along two very scientific young men -- my sons, Louie, 10, and Gus, 6. I profoundly hope they add a spirit of first-viewing to what we see there, and I thought it would be worth looking at our travel in the kind of observational spirit the |

Thing one is passports. I have a deep love of passports, and getting passports for my sons was, though something of a pain in the patoot, an emotional experience for me. Once you have a passport, you can go anyplace, and that's a kind of threatening thought when the passport holders are in elementary school.

Just the same, it's thrilling, too. A passport is a document, a souvenir, a create-as-you go memoir, and I gaze at my old passport with a fondness bordering on the absurd.

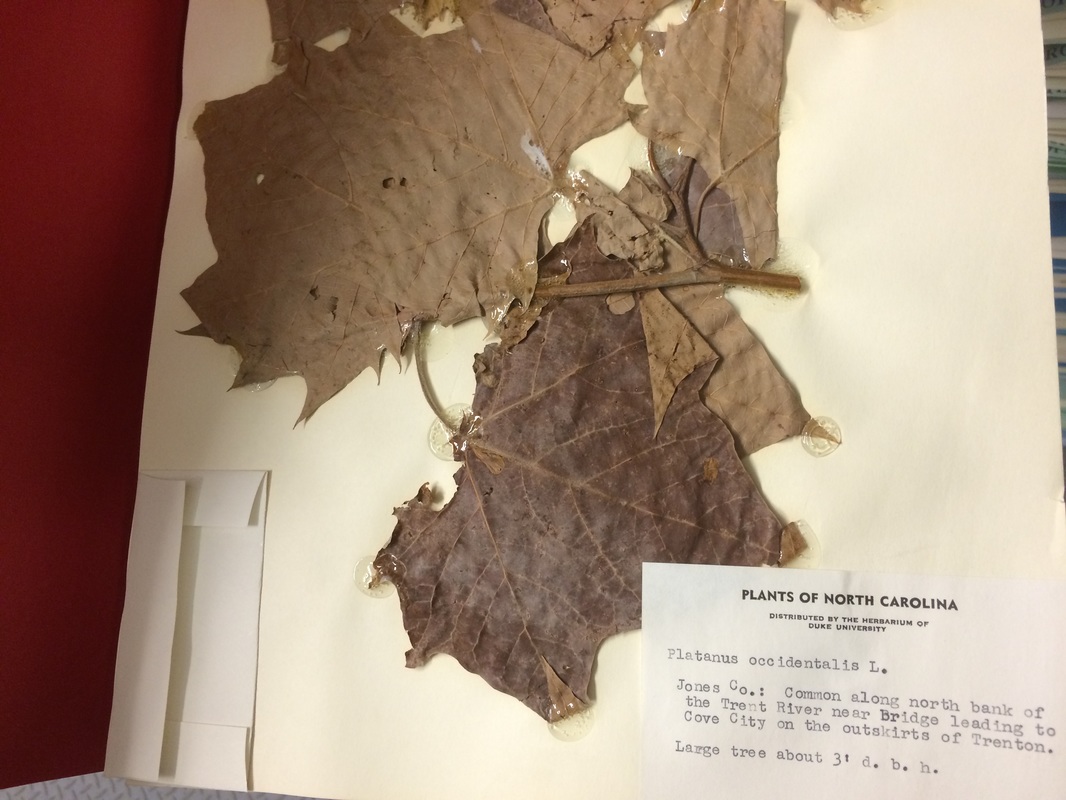

For one thing, I'm in favor of actual things. Of paper things, of things with stickers and stamps, with initials and dates and signatures and embossments. A passport carries more than thousands of years of history of international border control. Lawson would likely have had nothing in the way of passport, though he might have had some sort of letter of introduction. Not so today, with our tight focus on borders, but that's not a bad thing at all. A passport carries with it a memory of your actual physical movements on an actual physical planet. A passport is real. Which, today, is no small matter. Electronic ticketing means that instead of colorful stickers on steamer trunks or even cardboard seat-assignment stubs, most travelers return with no document more romantic than a folded sheet of copy paper. In this dreary virtual universe, of paperless voting and checkless bills, of correspondence without stationery and reading without pages, the use of a passport -- a real honest-to-goodness travel document, which a real person will stamp with real ink -- seems stabilizing and even comforting.

Which is another important benefit. Picking up passport stamps is a worthy and satisfying goal. You can show them to your friends upon return, compare them while you travel, flip through pages of them as your airplane descends into foreign territory and you anticipate passport control, a foreign language, the need to find transportation, lodging, food. Your passport stamps remind you: I've done this before; I can do it again.

So we're planning now. We've got the folder of every single printout, itinerary, receipt, and schedule, which we always know where it is -- something of a wonder in our house. Little piles are appearing: bathing suits here, raingear there, a little travel diary for each kid, with pens, pencils, sharpeners. We're getting ready to go somewhere. It's not undiscovered, but it's new for us.

We'll keep you posted.

P.S. A little note -- parts of this post appeared in somewhat different form in 2007 in a freelance story I wrote for the News & Observer. If there were a way to link to it, I'd do that in a second. No such luck. Man, newspapers are just charging ahead in this digital universe, are they not?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed