This I did not see -- but I turned towards her in time to see her arms and head disappear within, as she scrabbled inside to recover them. Seeing her southern latitudes extending from the tree while northern hemisphere wrestled with the insides of the cypress, I found it impossible not to think of Pooh bear.

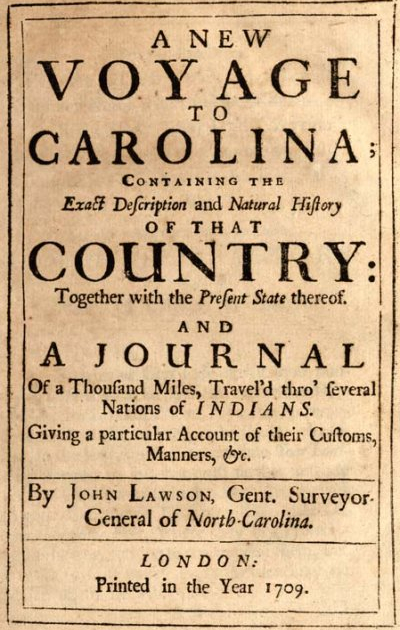

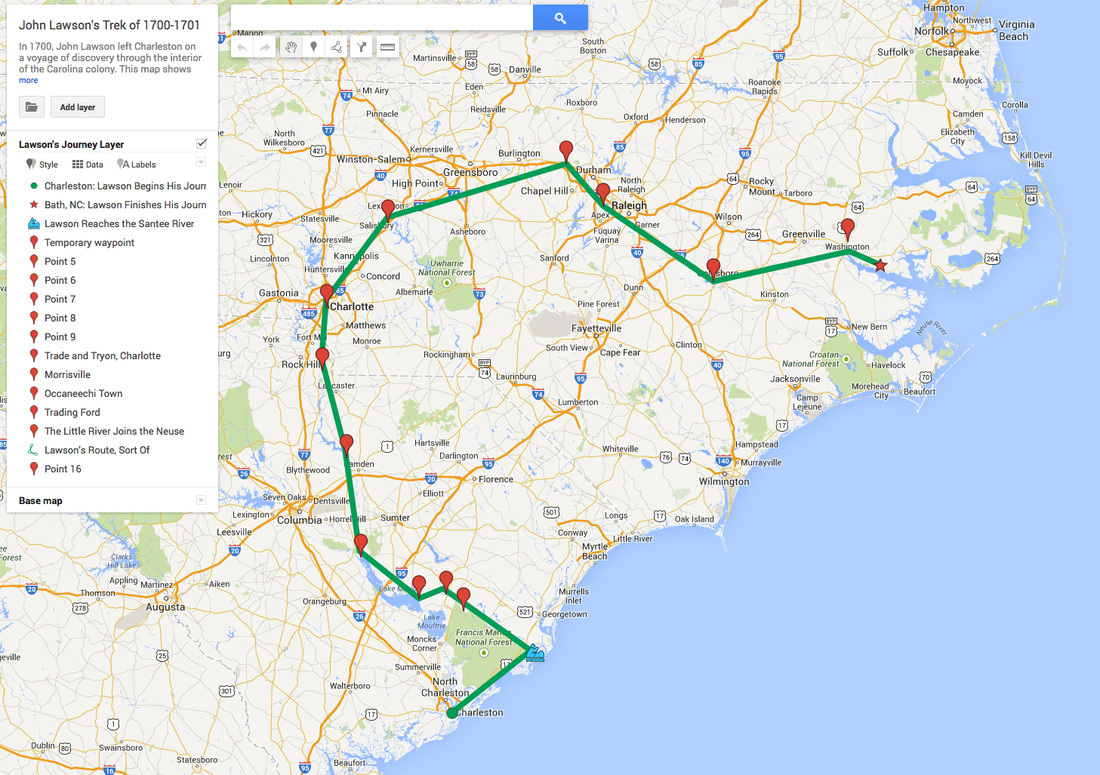

Traditional description of Lawson's trek involves some sort of assignment from the eight Lords Proprietors of the Carolina Colony. In the introduction to the current version of Lawson's A New Voyage to Carolina the author says thus: "Nothing is known of Lawson's sojourn in Charleston until December, 1700, when he was appointed by the Lords Proprietors to make a reconnaissance survey of the interior of Carolina." Interesting enough, but as we say in academic circles, nuh-unh. Lawson clearly took his journey, as his delightful book amply documents. Why he took his journey remains enigmatic. Lawson's family was well connected in London and could easily have had contact with people of that stature, and Lawson was quickly well connected with influential colonials like James Moore, who became governor of Carolina in 1700 and had before that made forays himself into the western backcountry. But we have no evidence that anybody paid, told, or even asked Lawson to go on his journey. We just know he went.

She reads the country like a tracker, too. We found our first cypress swamp when an hour or so into our first day of hiking she narrowed her eyes and said, "That drops off quickly," pointing to a line of trees evident to her but not to me. We left the forest road, descended a few feet, and yes -- there was a swamp: a low bowl, with the obligatory bald cypress knees, tupelos with spreading bells at their trunk bases, and water rendered black by the tannins from leaves, bark, and pine needles.

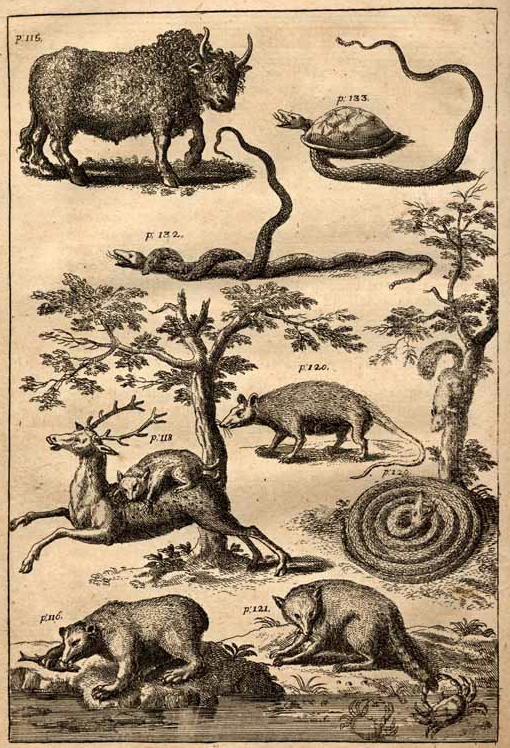

Days passed like this. As an ecologist Katie's training is, basically, in noticing things. My friend and fellow Lawsonian Tom Earnhardt has described Lawson as "a great noticer" -- his book is full of things that he points out, in lovely, satisfying prose, simply because he notices them. That's the value of his book -- not so much that he discovered things, but that he put down what he saw in a way that we can still understand. On Bull's Island, on the coast, for example, he described the first jellyfish he'd ever seen: "There was left by the Tide several strange Species of a mucilagmous slimy Substance, though living, and very aptly mov'd at their first Appearance; yet, being left on the dry Sand, (by the Beams of the Sun) soon exhale and vanish." The slime molds Katie studies Lawson never mentioned, but they’re bizarre creatures that are not fungi, though they used to be classified as such. Some of them exist in enormous supercells with thousands of nuclei; others exist as single-celled protists but on a chemical signal suddenly begin functioning as a unified organism. (Neither of the two we saw in the tree stump looked about to league together to take over the world, but to be honest I’m worried about that now.)

"It's not just about deer and squirrels. It's not just a longleaf pine forest. I think it's more interesting what's going on down in the soil. On the level of the microorganisms.”

The rain stopped awhile and we heard only the wind high in the pines. The slime molds we had seen could grow in a short warm spell. “They fruit very quickly,” she said. “But I’ve never seen them in January.”

More silence. “I like that it’s all more complex than we can really organize in our minds,” she said later.

Overnight we heard owls. The next day we learned the lake we slept near was full of hibernating alligators.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed