This third segment brought along not a young ecologist but Rob Waters, a friend and colleague who had time to come along because he's retired. He and I walked together along roadways and on dirt paths through lovely old stands of live oaks and along fields some miles long.

Which isn't bad, and I'm not complaining -- I'm just pointing out. What Lawson undertook was a very physical business, and every Trek segment brings that home to me. That is, we're outdoors, all day long, every day. If it's hot and sunny, we hide under hat brims. If it's cold, we bundle up. If it's raining, we get all wet.

This may sound like cheating to you, but remember: I have previously pointed out how Lawson clearly never paddled his canoe, and I will also point out that Lawson didn't carry much of his own stuff, either. The day he gets out of his canoe he describes "having hir'd a Sewee-Indian, a tall, lusty Fellow, who carry'd a Pack of our Cloaths, of great Weight; notwithstanding his Burden, we had much a-do to keep pace with him." He describes other Indian guides as he goes along and is less clear about who's carrying what, but I don't think it's unreasonable to expect an English gentleman traveling with experienced traders and Indian guides to have kept away from most of the heavy lifting.

Anyhow, all this walking is hard on a body, and had you hung around with us in our luxe state park cabin while we popped our ibuprophin and complained about our maladies you probably would have laughed. And that was after days of easy walking -- next segment I'll be back to carrying my house on my back, so we enjoyed our ease while we could, and it was a treat to spend the days of this trek very lightly laden: knapsack with extra clothes, journal, copy of Lawson; fanny pack with lunch and water; little belt pack, worn wrong-side-to, with map, notepad, pens, iPhone, and lens kit -- and, of course, trail mix. I'm not saying it was a walk in the park, but it was a walk along the road, which turned out to be very pleasant.

Just the same, here's a picture of me walking down the road during the second trek, just so you can see what I looked like fully loaded.

That cheerful attitude never left Rob. After spending much of our first day walking along the asphalt of SC Route 375 we turned onto a dirt path through old fields, and though he admitted he'd be glad to be done, he took infectious joy in the dirt path, and we both just gloried in the loveliness of the last hours' passage. We were outside, in comfortable clothes, walking among trees and crops, seeing birds above and swamps below, passing beneath swaying beards of Spanish moss. It was not hard to just be happy, seeing the world.

But the noise grew loud enough that we noticed it, and we kept approaching for more than an hour, and finally one gate lay open with godawful noise emanating from within, so we had to creep in. We had seen clear cut fields, fields of new trees, and fields of uniform growth up to full size, but this was the only time we witnessed actual tree farming. And though nobody much likes a clearcut -- and the regular rows of a tree farm look like anything but nature -- a tree farm is still a bunch of pine trees, full of deer and wrens and woodpeckers, so we didn't complain. This Trek was rural pretty, not nature pretty.

All day long we had seen lumber trucks coming and going, loaded with a couple dozen narrowing trunks, or empty and on their way back. Rob recalled a summer he had spent back when they were still logging old growth timber near Seattle -- a single trunk of that old growth timber would fill the back of one of these lumber trucks, he said.

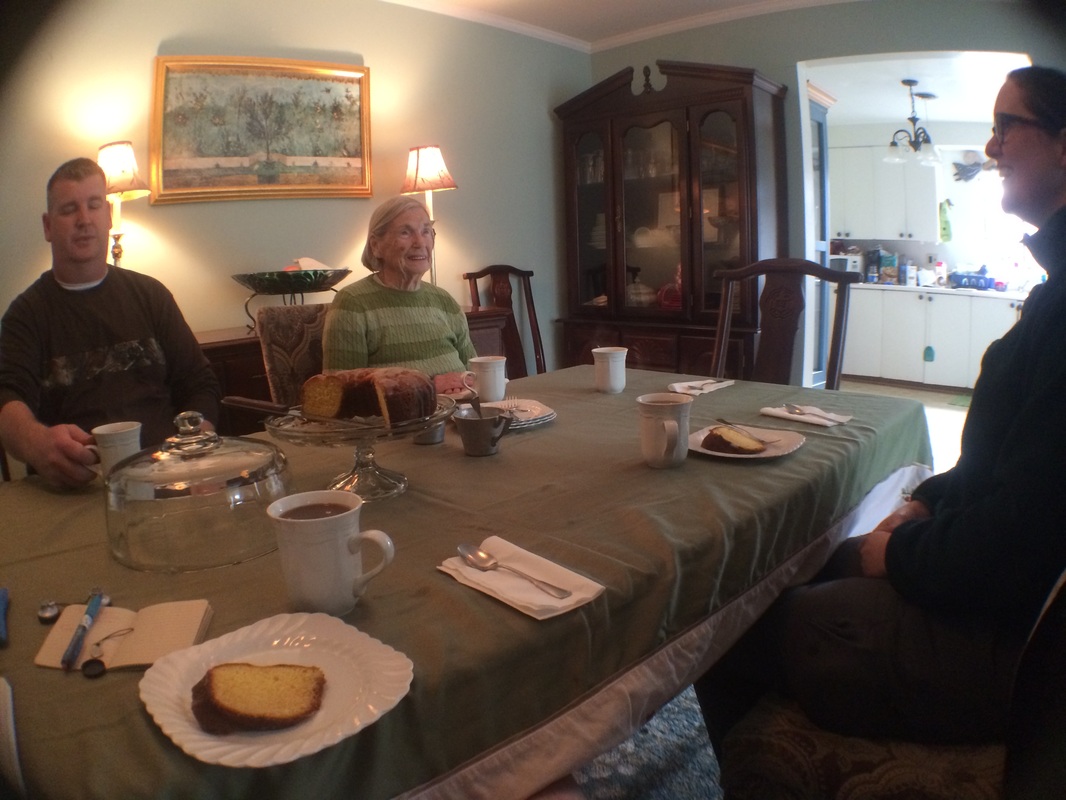

Coming up next: introductions to two marvelous people -- Peggy Scott, vice-chief of the Santee Indian Tribe, a descendant of the people who treated Lawson so kindly, and Val Green, chief of all the Lawsonians, who knows more about Lawson than anyone alive and has kept us on the path from the very start of this adventure.

Stay tuned. And take an ibuprofin. It helps.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed