""Still passing along such Land as we had done for many days before, which was, Hills and Vallies, about 10 a Clock we reach'd the Top of one of these Mountains, which yielded us a fine Prospect of a very level Country, holding so , on all sides."

Which is exactly what you see from the Charlotte Motor Speedway: when you sit in the stands you get to see cloud shows and hills falling away beyond. I showed up on a Tuesday evening, which meant they had a bunch of small-scale racing going on, and I sat in the grandstand eating chips and drinking soda pop just as Lawson would have done, had he had the opportunity.

Charlotte is the Carolinas' largest city and is really the only city with a big-city feel that Lawson would have passed, but even that doesn't last long. Ten minutes' walk from Trade and Tryon and you're in the North End, which welcomes you but offers mostly strip malls -- to say nothing of self-storage, vacant lots, and the homeless.

But: Nascar. Nobody needs to tell you Americans love cars, and the story of the growth of stock car racing is a remarkable tale of postwar American prosperity. So I found it delightful that Charlotte, at least, offers more than just parts and signs. The speedway was started in 1959 to cash in on the growing popularity of stock car racing, and construction went along just fine until the builders reached what Lawson probably could have told them, from walking the terrain, that they'd find: granite. "A half-million yards of solid granite," according to "Charlotte Motor Speedway: From Granite to Gold." That cost five times as much to cope with, and the speedway ran into the financial troubles that all enormous undertakings tend to have.

Anyhow, the region needed a speedway for the simple reason that stock car racing lives in central Carolina. You can find a million sources explaining how farmers growing corn learned that it was a lot cheaper to distill it and distribute it as whiskey than it was to transport and sell it as food, and how during Prohibition that meant delivering an illegal product. Which meant your car had to be faster than a police car but look perfectly normal. Add in that you needed cars that could rocket along straight stretches of highway but handle in both curving mountain roads during pickup and city streets during delivery and you've about covered every element of the racecars that fill the speedway.

| So, anyhow, the day I walked through the speedway wasn't running some enormous Sprint Cup race, with 150,000 or so people clogging grandstand and infield. It was an event in the Summer Shootout series with small cars running on a quarter-mile oval along the frontstretch, with maybe a thousand fans paying eight bucks for a ducat and enjoying the wreckfest. Racing is always fun, but my point here wasn't racing, it was Lawson. As I mentioned the spot is high on a ridge, and though the camping outside the track was hardly a thing of backwoods beauty, I managed to make a comfortable little home for myself even on a very hot night. |

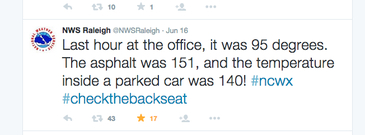

So anyhow, along Lawson and I went, north from the speedway towards Concord. Charlotte grew from a crossroads town to a textile town to a banking town and now is a big banking city. Concord's little twin brother, Kannapolis, was home of Cannon Mills and known as Towel City. and the walk north of the speedway to Concord was a study. For a long time in the heat that even at 7 am was brutal I passed racing-related shops -- restoration parts, cams, engine shops. Then came a long stretch of what I call the Anthropocene Suburban -- long stretches of road between small fields raising cattle or pines, the roadside ditches swaying with Queen Anne's lace, daisies and black-eyed Susans, primrose, Scutellaria (any of various purple-flowered mints), and dandelions.

Thanks for the sandwich, Lobo!

Thanks for the sandwich, Lobo! | | now the garden covers nearly a full city block, with a half-dozen fountains and grave markers including everything from boulders to obelisks to plain old lovely stone slabs. At left is a glimpse of what you'll see if you go to visit, and take it from Lobo and me, you should. So on I went, north of Concord to, as I mentioned, the delightfully named Old Salisbury Concord Road, where I quickly encountered something my old pal Val Green had bidden me to look out for: an |

| enormous granite outcropping, right along the road, described by Lawson: "We went about 25 Miles, travelling through a pleasant, dry Country, and took up our Lodgings by a Hill-side, that was one entire Rock, out of which gush'd out pleasant Fountains of well-tasted Water." No gushing fountains now, though the rock face remains, running along the left of the road, sometimes covered in hanging foliage. I did not sleep there. Along I went, though, until the road begin to diverge away from Kannapolis. That was as far as I cared to go in that blasting sun, having covered about twelve |

9 feet of bronze intimidation.

9 feet of bronze intimidation. One has surely heard of Dale Earnhardt, the Kannapolis native sone who became a legendary stock car racer, perhaps the best of all time. He died in a wreck at Daytona in 2001, but long before that the taciturn, stubborn competitor had become a symbol for the rural, Southern fans of Nascar's early explosive growth. When he died, though not everyone in mainstream culture understood this, in the South and across Nascar America it was like Elvis had died. Earnhardt's father, Ralph, was a racer -- racing was his way out of the Kannapolis textile mills he worked in. Earnhardt too was uneducated and headed for the mills, but his racing gave him a way out. His success on the track became a touchstone for generations of Carolinians, and his death broke hearts.

So in Kannapolis, if you go to downtown Kannapolis, you won't find a huge amount -- on the redevelopment scale it's behind Concord and nowhere near Charlotte -- but you will find a statue of Dale Earnhardt, in a little plaza built for that purpose. It's part of the Dale Trail, a collection of Earnhardt touchstones you can visit. You can visit Ralph's grave, the family's old neighborhood, roads named after Earnhardt, "Idiot Circle," the cruising area of Kannapolis, and of course the plaza, which has not just the 9-foot bronze statue but a granite monument and a circle of benches. You can also drive to race shops and stores and such, but you get the idea. Lawson walked through here, describing the place to the world for the first time; no statue. Washington came through here on his tour of the South, solidifying the nation in the aftermath of the adoption of the Constitution. No statue.

Earnhardt drove race cars, and he gets a statue. I say this not in criticism but in description. You want to understand the South? Look at who the people raise up. In Camden, South Carolina, you see an awful lot of the Indian chief King Hagler, and you know why: he was a local. Washington rode through; Lawson walked through. But Earnhardt was a local. Earnhardt Carolina loves. Let's hope they come to love Lawson as much.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed