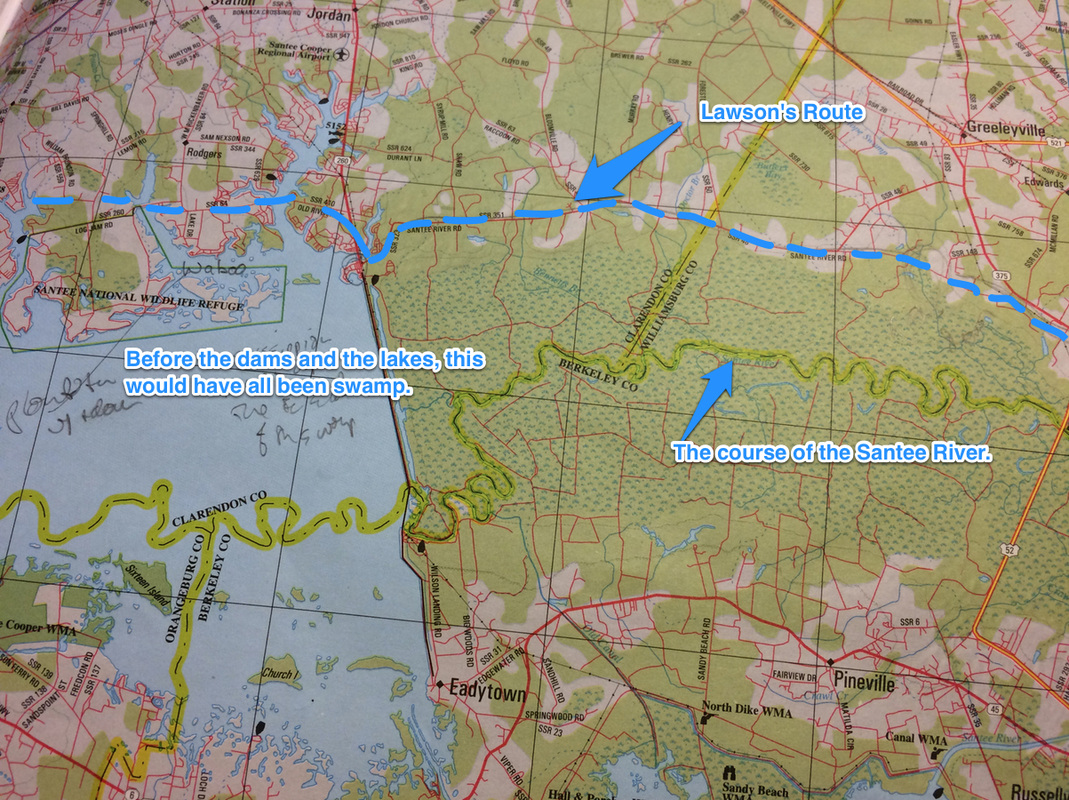

From the Huguenot settlement Lawson continued north, likely following an Indian path along the edge of the swamp on the northeast bank of the Santee River, now called the Santee Swamp. The first native people he met there were the Santee Indians, whom he described as "a well-humour'd and affable People; and living near the English, are become very tractable."

Says Lawson, "They came out to meet us, being acquainted with one of our Company, and made us very welcome with fat barbacu'd Venison," and let me promise you, Carolinians have been welcoming visitors with barbecue ever since.

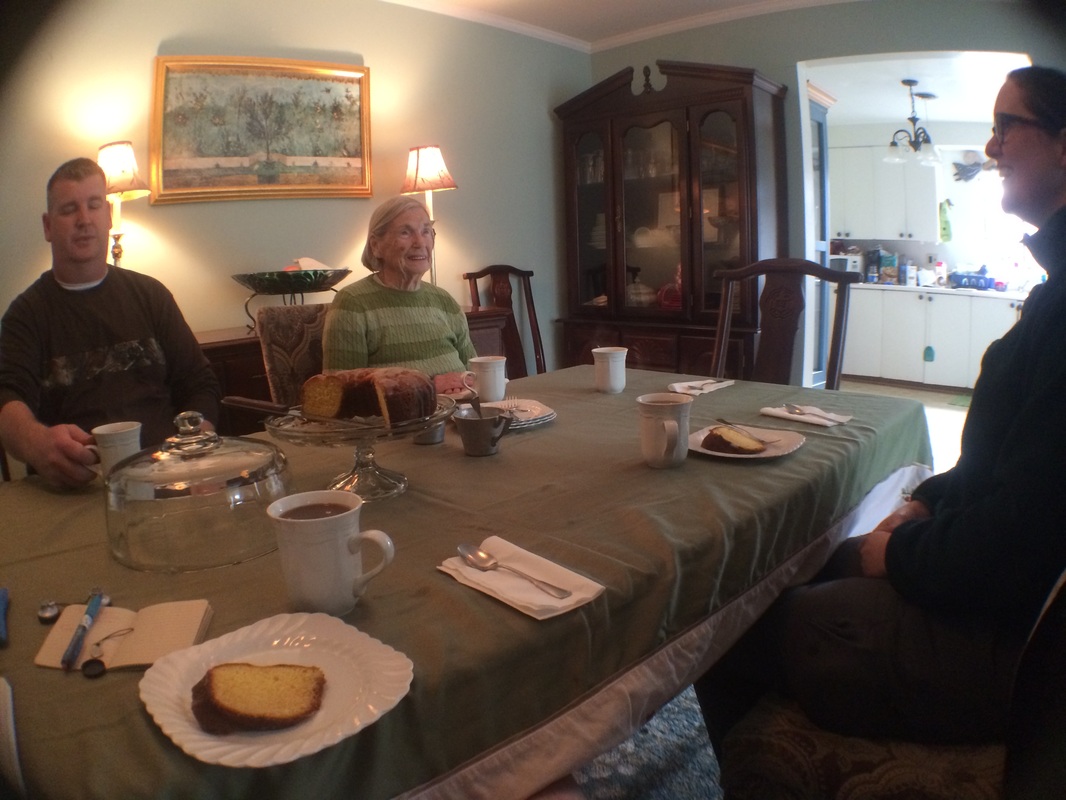

All of this is to say, from the wonderful hospitality of the Huguenots (which their descendants recreated with me), Lawson advanced to the wonderful hospitality of the Santee, and I was anxious to see if I could meet their descendants and see how time had treated them. I was thus thrilled when Chris Judge of the Native American Studies Center of the University of South Carolina-Lancaster gave me contact information for the current chief and vice-chief of the Santee, Randy Crummie and Peggy Scott. Chief Crummie was working seven days a week keeping body and soul together, so he asked me to reach out to vice-chief Scott, whom I now think of as Peggy and regard as a friend, and who welcomed me to her region just as openly as her ancestors did centuries ago.

| We had invited Peggy to meet us on the road, and to walk along with us for a while as part of the Trek. But schedules grew complex and we ultimately met Peggy in our luxe cabin at Santee State Park, named for her ancestors. Peggy shared the life of a modern member of the Santee Indian Tribe, and let me tell you, it's not all barbecue and affability. "We're the only race to have to prove who you are," she says of American Indians as a minority group. By the way, like many I've spoken with, Peggy tells me she perceives Indian and Native American as equally inoffensive terms; I use the two interchangeably. |

She attended an Indian school, segregated and denied resources to the point where she says "I didn't know what a gymnasium was. I didn't even know what a library was." A couple of her friends went to the high school but were treated so badly they left. She says when she was in fourth grade the Indian school closed and she moved into the middle school, where she describes a segregated system having white and black drinking fountains. If an Indian child was thirsty? "The teacher or principal would go get you a paper cup of water."

It's no surprise, of course. Indigenous peoples like the Santees were already reeling from the results of European contact by the time Lawson met them in 1700. Smallpox had devastated them, rum had taken them unawares, and they had been not only uprooted from their land but commonly enslaved -- Indian slavery was such an enormous undertaking that before 1715, Charleston actually exported more Indian slaves than it imported African slaves. The Santees numbered around 1000 in 1600 but declined as precipitously as their neighbors. In 1711 they fought with the British against the Tuscarora (who had killed Lawson), though by then their number was so reduced that according to The Indian Slave Trade they sent only a portion of a group of 155 that comprised at least seven tribes' worth of warriors. in the 1715 Yamassee War in South Carolina that finally sealed the fates of the Southeastern tribes, they fought with their Indian neighbors against the colonists, but it was basically over when the Yamassee lost. The remnant of the Santee (80 or so people in two villages) moved up the river to join the Catawba or melted into the swamps, just trying to keep away from the colonists, over the years mixing with other outcasts like escaped slaves and poor whites. The wonderful Those Who Were Left Behind tells the story of the South Carolina tribes who remained, explaining how the current Santees may descend from a group of indeterminate Indian background who found themselves a small piece of land southeast of the Santee River in the mid-1700s and have been around there ever since, reasserting the name "Santee" in the 20th century. Exactly what blood runs in whose veins is a subject for debate -- constant debate, given that the Santee Tribe is currently recognized by South Carolina but not the federal government -- but Peggy has no doubts.

"I was born in the middle of my tribe," she says. "My father and the elders delivered me in my mother's bedroom."

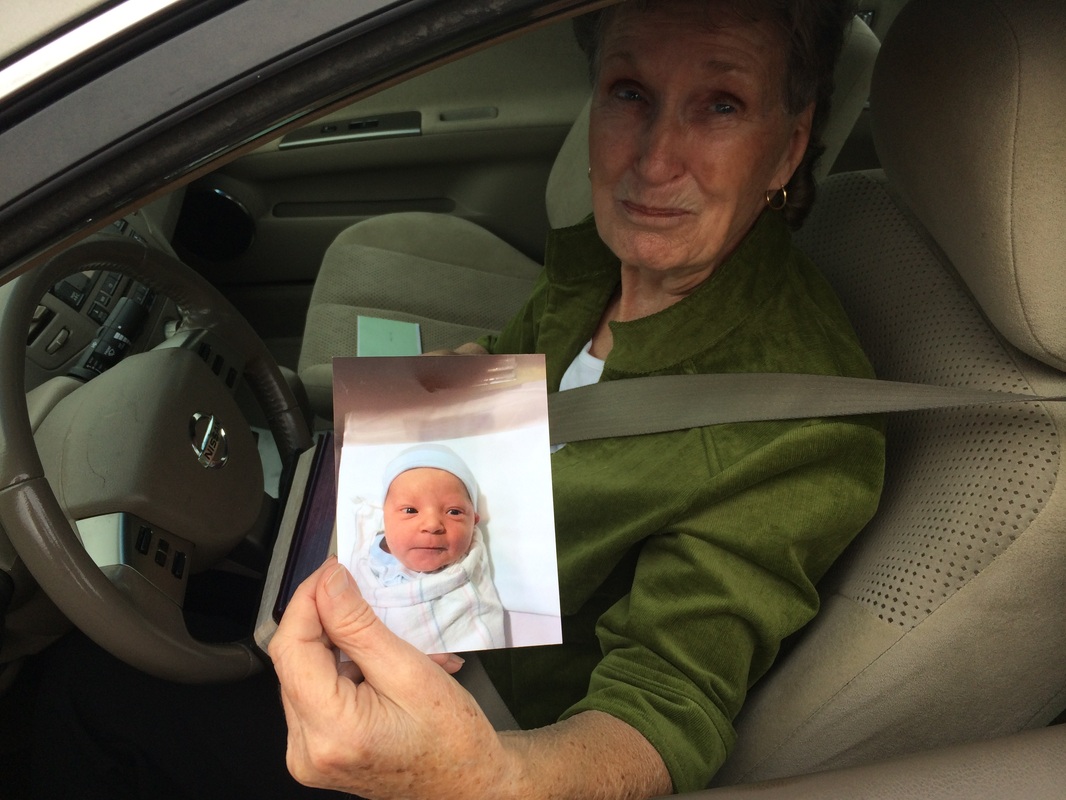

It's still complex. She has a son. "The old saying is you have to have one to put in this world and one to put in the other world," she says -- a child for the Tribe and a child for the greater society. For her part, she has embraced all aspects of her complicated background, though that's not always the case. She talks of tribe members who feel no need of tribal culture, seemingly buying into the old image of Indians as uncivilized. When her son was born, her father urged him to take advantage of his light skin, but Peggy smiles. "I raised him differently." He lives in Charleston, fully integrated into the world at large. But now engaged, he wants to be married on tribal land and include Santee tribal customs in his wedding.

She's worked much of her life for the betterment of her tribe. She's taken the special training you have to take as you try to work your tribe towards federal recognition, she's traveled to pow-wows hither and yon, and she has spent years of her life helping her tribe get, literally, back on the map. "We have land," she says. The U.S. Forest Service had an unused fire tower near Holly Hill, South Carolina, she says, and "We got an idea."

She worked it, eventually getting the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources to donate the land, and the Orangeburg County Council provided money for a building, which opened in 2013.

Some of it they can't have, though.

"I'm part of the South Carolina Native American Ladies Traditional Dance group," she says. There was a time, after a significant accident, when Peggy could barely function, much less dance. But as her rehabilitation continued, she ended up able to dance, and a dance was scheduled at a pow wow the Santee hosted.

Let her tell you about it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed