You betcha. Out in public, pointing and shooting is your right. Be confident and firm about that.

You betcha. Out in public, pointing and shooting is your right. Be confident and firm about that. Shoveled snowpiles taller then most people; cars under feet of snow; the infinite variety of weird human response to snow; and an entire Pantone deck of different colors of slush. I took pictures of snowbanks and falling snow, videotaped streetlight snow, recorded the muffled sounds of snowy streets.

And when from a public street I pointed my camera at a little girl playing in the snow, her mother barked at me: "Please stop taking pictures of my daughter!"

So naturally I stopped that, though I wanted to scream at her. Given that we stood in a public space -- stores, schools, churches, intersections all nearby -- I'd be willing to bet you the three of us were under surveillance by at least two security cameras every second we stood outside. Her cell phone calls were probably monitored by local and regional -- and were certainly monitored by national -- agencies. She probably hasn't had an email that didn't run through a random bad-guy filter for a decade or more. And despite all that she just goes about her business, as we all do.

But me she could see taking a picture of her daughter, so she attacked.

Now, as a working journalist I think about this stuff, and it's all best clarified in this sentence, from a New York Times blog in 2012.

You may draw your own conclusion, but a new law recently passed by the state of Alabama took the insane belief that reasonably taking someone's picture in public is some sort of violation of a vaguely understood right of theirs and tried to codify it into law, which would have destroyed not just news photography but all public photography. Fortunately the governor vetoed the law before further mischief occurred.

All of which brings me back to the post I put up a bit ago about land and rights, in which I complained about how affronted some people get when you step on their land. This generated some wonderful responses that I wanted to share with you.

First, here's a piece from Ellen O'Brien, a Facebook friend-of-a-friend who commented on my friend's share of the piece. At my request Ellen tidied up her comments for use here:

"Your column about walking the Lawson Trek, and your surprise at the responses of some of your readers, brought back some good memories of my own salad days, when I was a young reporter for the Atlantic City Press, and spent many weekends canoeing with my then-boyfriend on the West Branch of the Delaware and Susquehanna Rivers. We did exactly what you did, only we did it by river. We canoed until we were tired, or it was getting late, and then disembarked and pitched camp on land that was sometimes state-owned, but probably just as often, not. Once or twice, as I recall, we even used the private-property postings as kindling.

"We pitched camp and (he) built a campfire from blown-down sticks and we sat until dark in the privacy of the river bank until it was time to bed down. And we were up and on our way not terribly long after daybreak.

Good days. A city girl, I learned to like all of it, and sometimes still miss the feel of a canoe moving through the water.

"That was a different time, and the country was filled with movement of all kinds -- political, social and personal -- and most our peers would then have snickered at the kind of possessive outrage that some of our peers now seem to wallow in. Enough said. "

Is that not lovely? I also heard from my friend Fritz, who owns property on a lake used by fishermen, mostly without permission. "As to property rights, to me, it's about liability. Maybe you won't litter or your campfire set the woods ablaze but the property owner will bear the responsibility if you do. Many of us feel it's easiest, especially after prior abuses, to just say no." Prior abuses have included incidents like this:

"One day, arriving at my lakeside estate, the entrance was blocked by an unknown car. I ambled over to where the folks were fishing, identified myself and explained that guests were expected within the hour and they would have to leave for now but were welcome to return whenever I wasn't around. Righteously indignant, they told me they had been fishing there since the lake was built and that they had permission from the owner to do so. I explained that, having prior knowledge that the lake was to be built, I'd purchased and had been paying taxes on the land since before it was a lake and asked who had mistakenly granted them access to my property. It ends up that my next door neighbor, evidently not wanting to allow the use of his land, had told these folks to fish on my side of the inlet. Later that summer, on my next trip there, I had to clean up a case of beer cans and a bag of trash from their fishing spot."

Can I get in line behind the property owners to help kick these knuckleheads off their property? But in the end Fritzy comes down on the side of decency and goodness: "I began paying taxes on that place in 1977 and have the thickened skin that comes from dealing with several such abuses since then. Most folks appear to believe that leaving a mess is required to prove their presence. A fisherman once told me that he didn't litter every chance he got. He can use my land any time he wants."

Working hard on being like that fisherman, I begin all interactions with land giving its owners the benefit of the doubt: I assume they're like Fritz. If I'm wrong, I'll just apologize and be on my way.

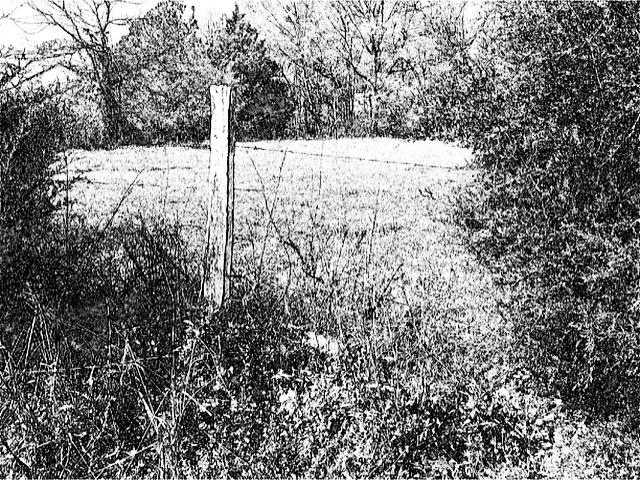

Here are two images; on the left the original, on the right the gussied up one that went to Instagram. Are they both nonfiction? I think so -- what do you think?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed