And stories are why I'm out there, really. I finished the fourth and most recent segment of my trek at the tiny town of Horatio, where I stopped at the Lenoir Store, which has been at the crossroads since at the very least before 1808, though how long before that nobody knows -- it pops up in the historical record in the will of one Isaac Lenoir that year, and it's been in the same Lenoir family ever since, represented on a maps from 1825 and another from 1878, by which point the current building stood. It turns out to be the longest-standing continuously run business in Sumter County and probably the whole state, according to my guide, Bubba Lenoir.

The Lenoir name is far from unknown in the south -- Lenoirs in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee all trace their line back to mariner and tobacco farmer Thomas Lenoir (the French name gives a clue that he, like many other French, came to the colony seeking the religious freedom Carolina offered) who lived first in Virginia before finally settling in North Carolina. Of his sons,Isaac was a soldier in the Revolutionary war and brother to General William Lenoir, who has a namesake city and county in North Carolina. South Carolina has this store.

No such luck. When I came into the store footsore, hungry, and cold, I found no coffee or hot food -- there just aren't enough people in Horatio to justify it, Beverly told me. Like many of South Carolina's small towns, Horatio is losing population, and left behind are large plantation farms and retired people. Given that the store didn't even have central heat -- Beverly stood in front of a space heater and smoked wearing gloves -- I was glad for the shelter, the company, and the surroundings.

And the story. Beverly clued me in, giving a tour of the various old objects still on the store shelves, reading some aloud, and filling me in on family lore. It's one of the oldest post offices in the country and has been the subject of considerable resistance when the USPS considers closing it. As much as I loved it, I didn't want to move in, so I reached out for my ride. But when I called my associates 30 miles south at Pack's Landing, a supply store and boat landing on Lake Marion where I had left my car days before, I found that nobody was prepared at that moment to come get me, and though someone certainly would come and get me, exactly when wasn't entirely certain, nor at that moment easy to predict.

The house Bubba had emerged from was built in 1954, and Bubba told me the story of its predecessor, built in 1760, burning on Thanksgiving morning, 1953: "Daddy said 'Don't grab nothing, just get out,'" he recalled. "The whole house was built out of fat lighter" -- pitch pine, which burns like a candle. "We just did get out." Bubba stopped at St. Mark's Episcopal Church, to which he had the keys, and we explored the cemetery and the church itself, established in 1757 and currently in a building, created of local clay, built a century later.

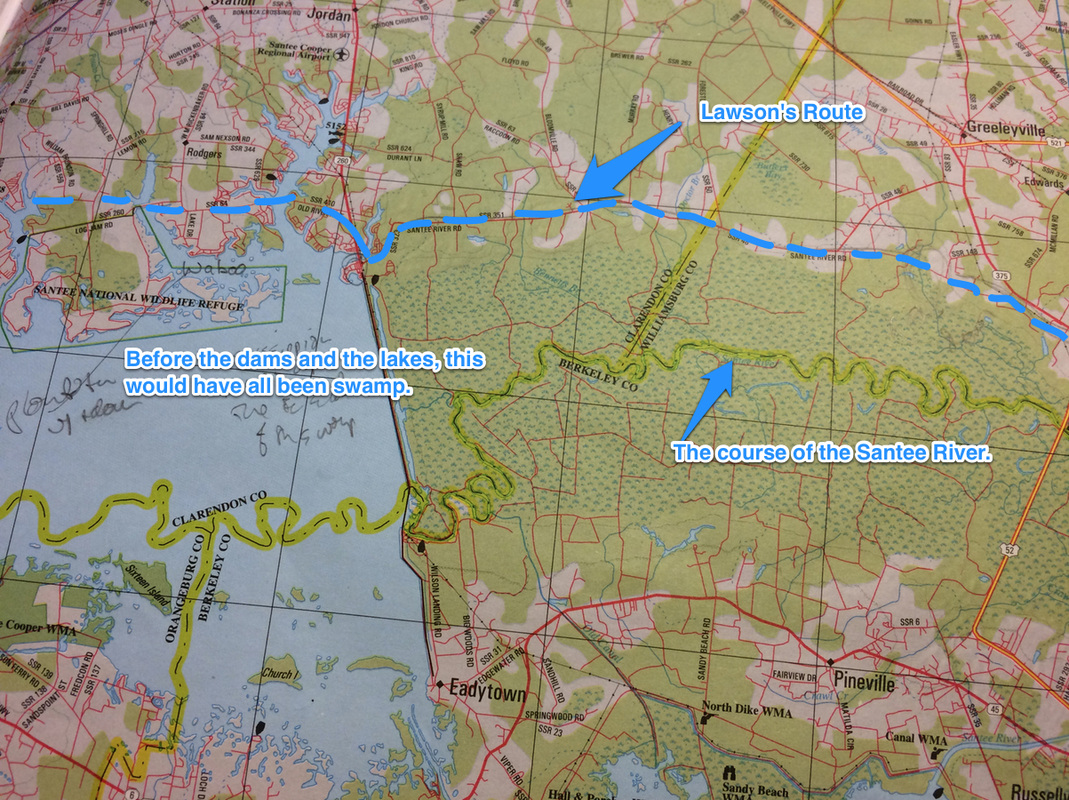

Anyhow, between the Richardsons and the Lenoirs and the abandoned railroad I had camped near I got to feeling I had really managed to learn a bit about Sumter County, to say nothing of the route Lawson would have trod. The Lenoir Store only stood where it did because the old Mississippian Indian trail to the Santee Indian Mound ran by there, and that trail had become the dirt road along which I had walked, and that had given rise to the railroad -- since abandoned -- and the asphalt Horatio-Hagood Road I'd finished my trek segment on.

Bubba and I cheerfully conversed until we pulled into Pack's Landing, where talk instantly turned to the kind of good natured foolery that makes places like Pack's Landing -- and the Lenoir Store, and for that matter Sumter County -- the wonderful places they are. "What's the population of Horatio?" needled a fellow named Duck, who would have come to pick me up had I been more patient. He pronounced it HO-ratio. "Well, this morning it's about 25, since I'm down here," Bubba said, and off they went. They got into game wardens and how to manage them, they teased me about sleeping outdoors the night before in 10-degree weather ("You didn't have to worry about no mosquito bugs," Duck said, meaning me and Lawson at this time of year), and when I left they were talking about someone Bubba had played football against in high school.

Lawson took his long walk, basically, to see what was out there -- to meet the inhabitants and see the country. I felt delighted to have done just that.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed