| We found shelter from a steady downpour beneath the overhang of the Shulerville used oil recycling center. Katie and I managed to exchanged soaked capilene for dryer materials from our packs without scandalizing any passersby, and then we waited for our new friend, Douglas Guerry, to drive by to pick us up. I had heard from Douglas during the previous segment of the trip. Douglas was a descendant of one of the original settlers, Pierre Guerry, one of the original Huguenots who settled the lower Santee in the 1680s. He wondered whether as I approached Jamestown, currently mainly a crossroads near the end of my trail in the Francis Marion National Forest, would I like to see the site of the original town of the French Huguenots among whom Lawson spent a few days, the site now owned by the Huguenot Society of South Carolina. |

So we kept in touch, and when I headed down for the next segment we texted back and forth. I have lived in two countries and eight states, so the idea of spending time with a man who was born not two miles from where his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather hacked his home site out of raw forest was very exciting. Plus, like Lawson, I was traveling through to see what I could see; like the Huguenots of 1700, he was offering hospitality. It sounded like a fit.

Ecologist Katie Winsett and I planned to meet him on the second afternoon of our hike. We awoke that morning in our Francis Marion State Forest campsite and began our day by finding our complicated way to what are called the Blue Springs, one of the sources of the Echaw Creek that eventually feeds the Santee River. The springs are not on the map, and the roads through the forest are anybody’s guess, though with enough maps and texts we found them. Though the swamp was too high for the springs to be blue, we did find the swamp, perhaps the loveliest of the cypress-tupelo swamps in the forest. Katie has been astonished at how similar these swamps are to the ones she's studied in Texas and hopes to compare them. The wide bells of the cypress trunks, the knobby knees emerging out of the black water like serpents, the swaying spanish moss all made this one seem like a swamp right out of central casting. We refilled our water jugs.

| What causes the swamps to rise is of course rain, and rain we'd had plenty of the night before -- and the area had had for the last few weeks. So we kvelled over the swamp, took pictures, absorbed the water line, and as the rain began again, instead of turning deeper into the forest for more exploration we started heading out to the road, where we could message Douglas, who planned to take us to see the Huguenot memorial at the site of the original town. | |

Douglas drove up twenty minutes later, with his brother, Mark, and his mom, Jean, in the car with him. They piled cheerfully out and announced that we wouldn't be able to see the original plot of land after all -- it's right on the Santee River, but surrounded on all sides by another property owner who is touchy about people crossing his land. About what may cause the owner to fear for the outcome if we were allowed to cross his land you may draw your own conclusions.

We conversed briefly about the history of the Santee River. Its waters were mostly diverted into the Cooper, towards Charleston, in the 1940s, creating Lake Moultrie and Lake Marion, but the diversion compromised the Santee ecosystem and filled Charleston Harbor with silt. A rediversion canal was built in the 1980s, which is helping, but the mingled waters of the Santee and the Cooper will never be the same as the rowdy, untamed Santee floods Lawson describes. Steamboats plied the Santee until the lakes were built. About the family denying us access to the Huguenot site Jean said only of their tenure in the community, “They’re not old.” She narrowed her eyes and nodded: “I know.” And mind you, Jean is herself a relative newcomer: she can trace her family only back to 1720 -- she’s the longest-standing member of the South Carolina Historical Society, but she hasn’t made the cut for the Huguenot Society, though her sons have, on account of their father. And when our good friend and sometime guide Eddie Stroman from McClellanville stopped by, it took her only a moment to connect with his people and place him with approval. So if Jean says a family isn’t old enough for her, Jean gets the win.

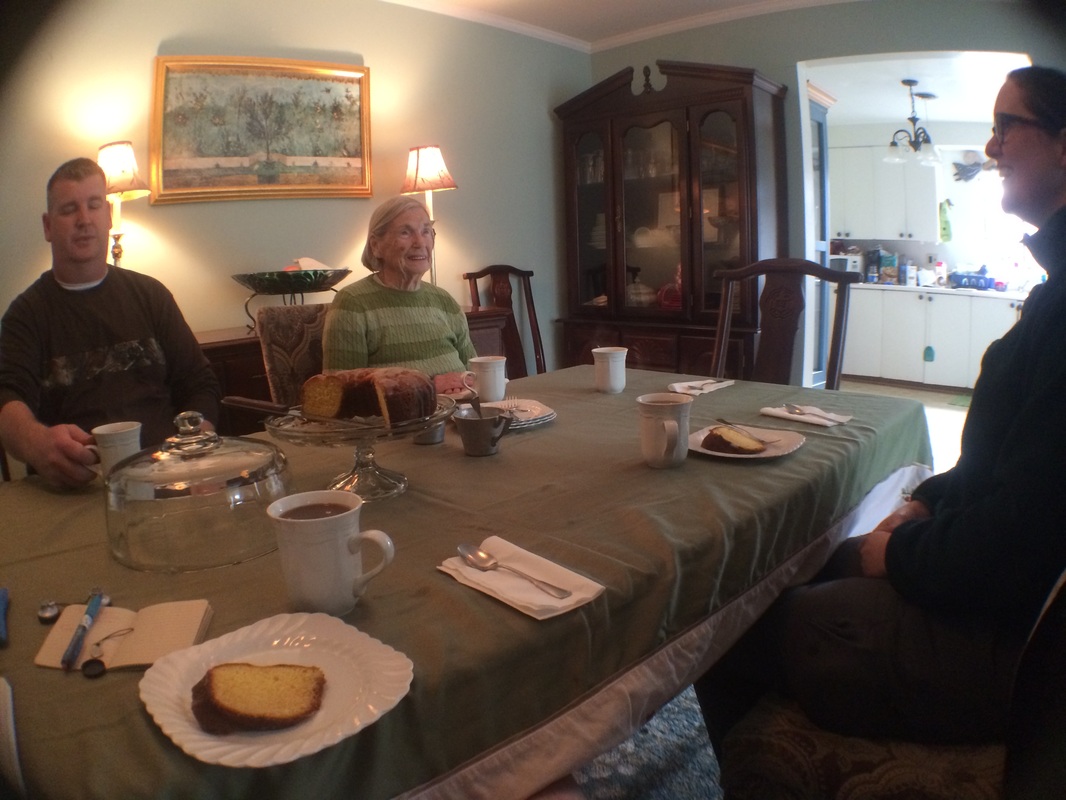

Then she invited us over for cake and coffee.

Jean made us coffee and brought out a bundt cake. “Welcome to Jamestown,” Douglas had said, “population 74 -- when Mark and I come home it goes up to 76.”

We had a lovely time. We discussed that in South Carolina, whose legal system is based on English Common Law, only the coroner is empowered to arrest the sheriff -- regrettably, the point had become germane recently. We talked about whether the misguided commingling of the waters of the Cooper and the Santee hadn’t accidentally protected the Santee from development, keeping much of the land of the national forest pristine. We talked about the area churches -- the first recorded Episcopal clergy appeared in 1687 (Lawson talks of being assisted across the creeks by “very officious” French settlers, “whom we met coming from their Church”), though no trace of that church remains. A newer one went up on the old Georgetown road in 1768 -- it’s a red brick church that still stands on the old dirt road, with lovely cylindrical brick columns and cypress pew boxes. Jean told us that in its early days mistrust between the French and English settlers obtained: “the Huguenots used the back door -- the English used the front.” We discussed the Peachtree Oak, a live oak hundreds of years old on the nearby Peachtree Plantation, which stood until the 1930s, when it died. “If it hadn’t,” Jean said, “Hugo would have got it.” You can’t talk for more than 15 minutes in South Carolina without Hurricane Hugo coming up.

Anyhow. We probably stayed with Jean and Douglas and Mark (and Mark’s daughter, who showed up for a bit) for a couple hours. We ate cake and drank coffee, and we even chatted about political and social topics about which we very agreeable didn’t particularly agree. I would call it one my most delightful afternoons ever -- exactly what I left home for. Probably why Lawson left home, too.

We loved the St. James United Methodist Church as a place to eat and sleep. When the skies opened up in the middle of the night we appreciated it even more. Thank you, St. James United Methodist Church!

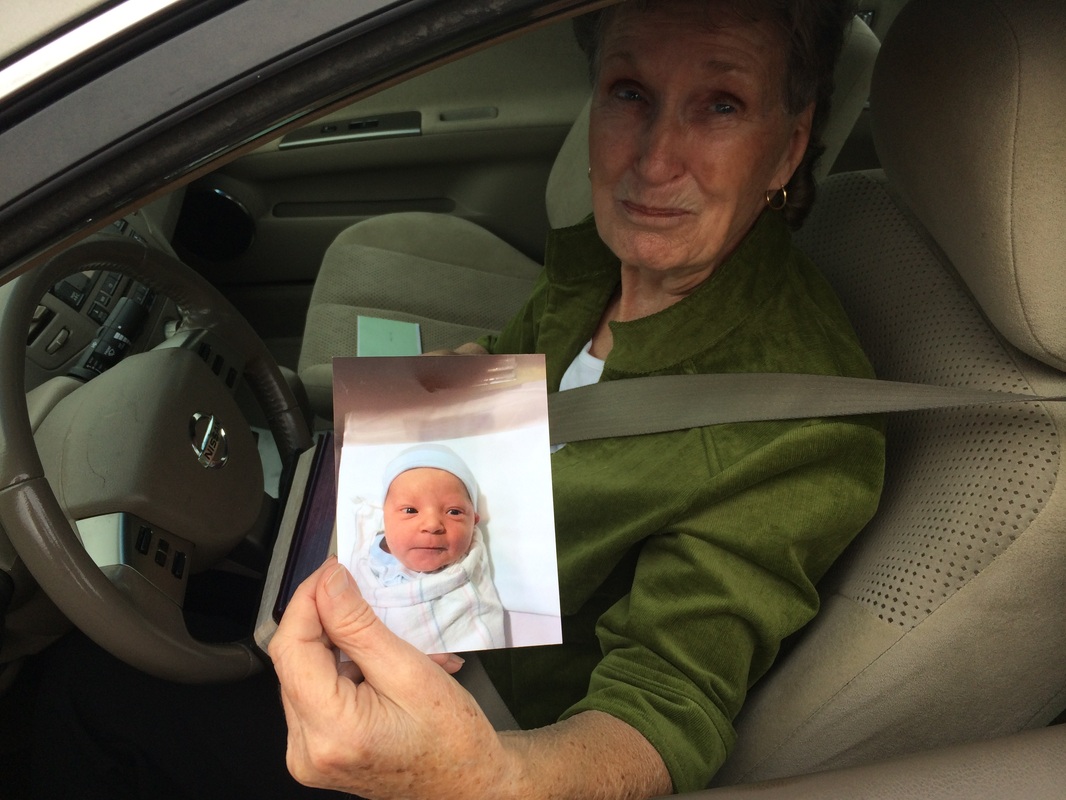

We loved the St. James United Methodist Church as a place to eat and sleep. When the skies opened up in the middle of the night we appreciated it even more. Thank you, St. James United Methodist Church! As we stopped to take a picture on our way out the next morning, Jean’s sister pulled up to meet Jean for church. She showed us a picture of her great grandchild, Malachi James, born in December. That makes him a Lawson Trek baby, and we hope the hospitality his ancestors showed rebounds to him all his life. Jean’s sister, by the way, introduced herself as Hazel. “Hazel Hughes,” she said. “No kin to Howard.” Rich just the same, if you ask us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed