I have mentioned Val Green like a million times, and I'm always promising to eventually give you the whole Val Green story, and today's the day.

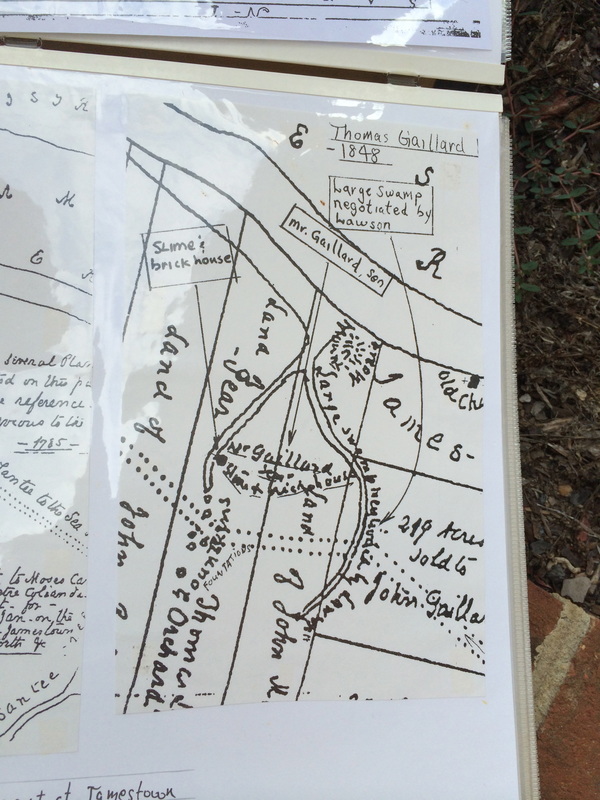

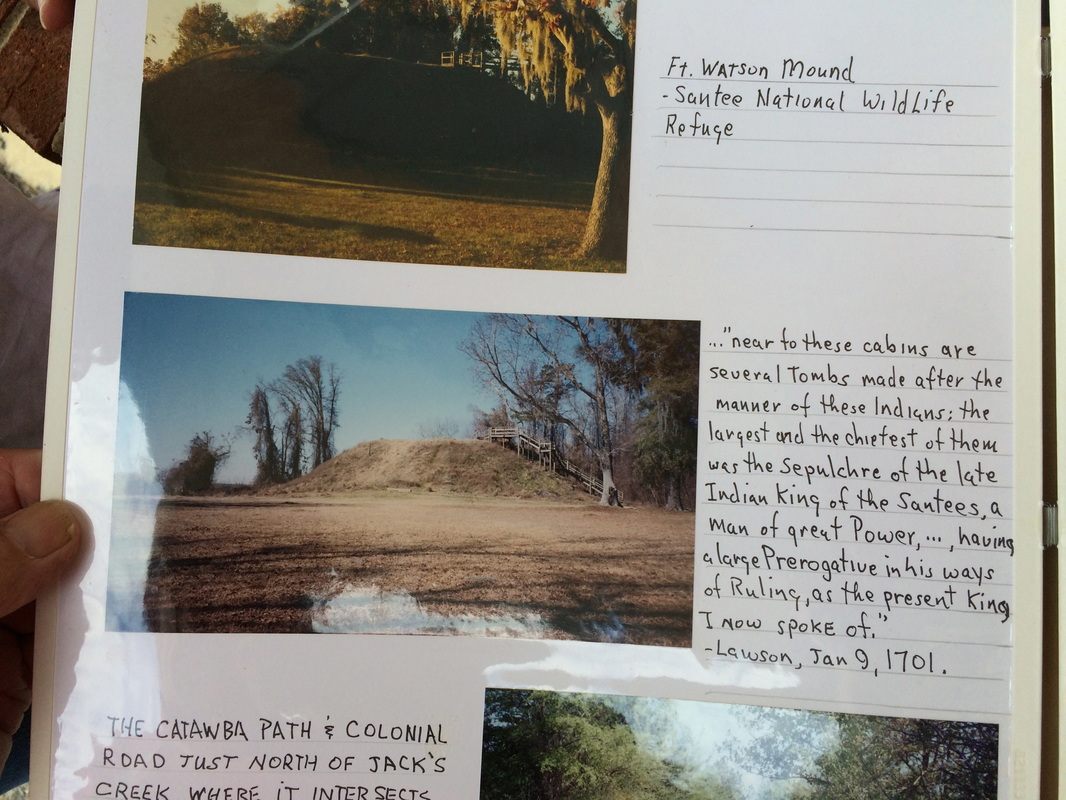

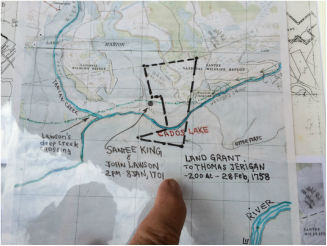

| In the photo at right you see me, in the stupid hat, taking notes while Val, in the normal hat, tells me things about John Lawson. Beneath Val's hand are a map and one of his Lawson scrapbooks, which he's made over the course of decades as he figured out the exact path of Lawson's route. Yes -- the exact path. Yes, decades. Here's the story. Val is a sewer engineer, and he lives in South Carolina. I met him because in my early days of research about Lawson I found a story from the Charlotte Observer in 2001 that mentioned his interest in Lawson and his pursuit of Lawson's path, at that time generally sketched but not completely known. So I poked around until I found him, and my understanding of Lawson would never be the same. In 1970, Val's (then-)wife gave him a copy of A New Voyage to Carolina as a gift, and he made his way through it, enjoying as he went. Two weeks into the voyage, Lawson describes being awakened: When we were all asleep, in the Beginning of the Night, we were awaken'd with the dismall'st and most hideous Noise that ever pierc'd my Ears: This sudden Surprizal incapacitated us of guessing what this threatning Noise might proceed from; but our Indian Pilot (who knew these Parts very well) acquainted us, that it was customary to hear such Musick along that Swamp-side, there being endless Numbers of Panthers, Tygers, Wolves, and other Beasts of Prey, which take this Swamp for their Abode in the Day, coming in whole Droves to hunt the Deer in the Night, making this frightful Ditty 'till Day appears, then all is still as in other Places. Val loved the sound of the place -- Tygers! Wolves! -- and thought he'd like to visit. Which brought up, of course, where might that place be? Well, at the time of the entry Lawson had been gone from Charleston a couple weeks, and according to his journal he'd been going up the Santee River for about a week. He had described the day before seeing "the most amazing Prospect I had seen since I had been in Carolina," a view from a hilltop over a swamp, looking towards far hills. Well, being from South Carolina himself, and knowing the terrain along the Santee River, Val suspected that Lawson must have been describing the top of the biggest hill in Poinsett State Park, which overlooks the Wateree River. In the distance from there you can see the Congaree, and the two join to form the Santee. Val visited the spot and it checked out. Further investigation to the south identified creeks that perfectly correlated to Lawson's descriptions of the terrain he had traveled. Val had found his spot -- and something to keep him busy the next four decades or so. | |

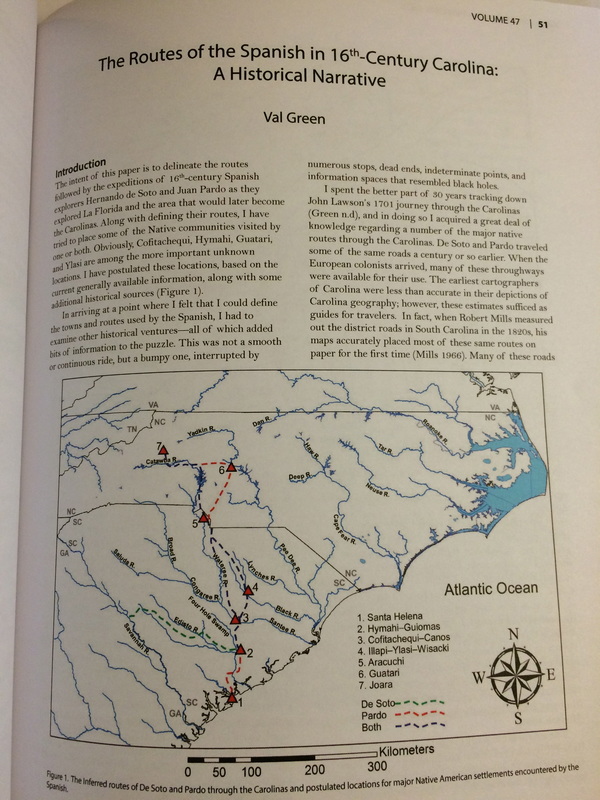

"The Routes of the Spaniards in 16th-Century Carolina: A Historical Narrative."

"The Routes of the Spaniards in 16th-Century Carolina: A Historical Narrative." And then Val moved on. Lawson led him to the Spaniards -- Hernando de Soto and Juan Pardo -- who wandered the same area a century-and-a-half before. In some cases the Spaniards used the same paths Lawson eventually used, and Lawson's trail is what led Val to the Spaniards.

| You scarcely need me to tell you that once Val gets on the case he stays there, so it's no surprise that the most current volume of South Carolina Antiquities (Vol. 47, 2015), which just came out, includes a piece by Val: "The Routes of the Spaniards in 16th-Century Carolina: A Historical Narrative." I have seen successful Ph.D. theses that were less carefully researched. I hear from Val right much still, and he came to meet me when my boys and I paddled into Bath at the end of my retracing of Lawson's journey. Now that I'm at work on the book of this undertaking, I'm sure I'll be reaching out to Val for more help and more background and more facts -- and I'll tell you about some of that. For the moment, though, just take a minute to appreciate Val. Val knows more about Lawson and Lawson's journey than any person alive. I am grateful to all the people who have helped me understand |

Anyhow, now you know.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed