Which might have been surprising, given that he took his journey during the coldest period of the Little Ice Age.

Lawson took his trek mostly over the winter of 1701, and he complained no small amount of the weather, though his first mention concerned its failure to kill pests: "Although it were Winter, yet we found such Swarms of Musketoes, and other troublesom Insects, that we got but little Rest that Night," he says of his third night on the trail, which would have been late December, 1700.

About a week later, he describes his first night inland, on the Santee River, as "lying all Night in a swampy Piece of Ground, the Weather being so cold all the Time, we were almost frozen ere Morning, leaving the Impressions of our Bodies on the wet Ground. We set forward very early in the Morning, to seek some better Quarters."

He further mentions the cold when he approached the Santee Indians, whose descendants I found so welcoming. Lawson and one of his companions got dunked in a river (they were drunk): "All our Bedding was wet," he says. "The Wind being at N.W. it froze very hard, which prepar'd such a Night's Lodging for me, that I never desire to have the like again: the wet Bedding and freezing Air had so qualify'd our Bodies, that in the Morning when we awak'd, we were nigh frozen to Death, until we had recruited our selves before a large Fire of the Indians."

My point is not that he was cold -- it was winter; he mentions being snowed on only on his last night on the trail. My point is only that snow was not an enormous part of Lawson's experience, so we lack recollections in his cheerful, observant tone of how colonists dealt with snow.

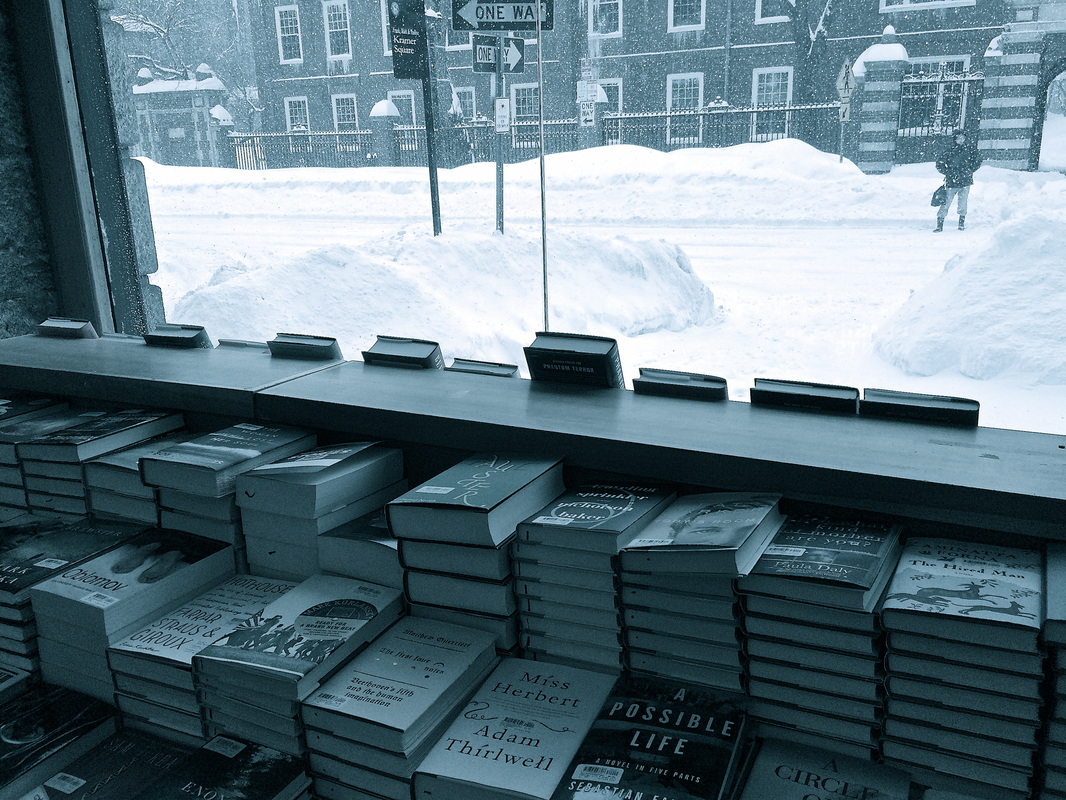

The Lawson Trek visited Cambridge last weekend, though, and snow was very much a part of my experience. Boston has set records for snowfall all winter long this year -- Juno, the storm immediately preceding my visit, was the sixth-largest snowfall in the city's history; the storm that accompanied my visit (and lengthened it through a delightful flight cancellation) was its seventh-largest accumulation in history, making February 2015 Boston's snowiest month.

Ever.

Cambridge thinks its streets should have as little snow on them as possible. It snowed on and off from Thursday evening when I arrived and then full-time from sometime Sunday Feb. 8, as I recall, getting 22 fresh inches before I got out. The first night, before acclimating, I awoke all night to reversing trucks and grumbling plows. When I flew out Tuesday, through those huge airport windows I watched enormous melters belch clouds of smoke as they sloshed loader buckets full of scrapings into roiling grayish brown soup. Every minute I spent outdoors the entire weekend I could either see or hear vehicles noisily pushing, plowing, salting, digging, carrying, or otherwise assaulting snow. Blinking yellow lights glinted off the snow especially at night.

On the other hand, their public transit doesn't mean much to them. MTBA is the nation's oldest public transit system, and it appears it's old enough now to break in the snow, which it did, shutting down train traffic completely on Monday Feb. 9. Fortunately, they plowed the streets so well my friend had no trouble driving me to the airport. The transit head noisily resigned after the trouble, but it was hardly her fault: you can't run what won't run.

People cleared out their cars once a day, creating in the blocklong snowbanks of five feet or higher car sized niches, as though for statuary. Cantabridgians often put chairs in the niches when they drive off -- you don't want to spend several hours clearing a parking space in front of your house just so someone else can park there. They seemed to like to wait until plows had gone by once or twice before attacking the piles; that way they could dig out once instead of having a plow suddenly fill back up a once-cleared spot.

Overnight, many pulled their wipers perpendicular to their windshields so they didn't freeze. Kids were coopted for labor, though roving pairs of older kids with shovels appeared to seize the capitalist opportunity to create value with their labor.

What I did was walk. Thrilled by the snow, I walked from my guest digs in far North Cambridge to MIT, on the Charles, time after time, taking every opportunity to walk through -- and get lost in -- the various squares, yards, bookshops, and other enterprises called Harvard.

There are rules, for example, about one-lane sidewalks, resulting from enough plowing and shoveling that instead of a clear sidewalk you have little more than a path between two huge snowbanks. You politely stand aside in a driveway or other shoveled spot for the person coming the other way to pass. If you wish to overtake someone going the same direction, do it like a car: wait for a wide spot.

If you're walking in the street, it's your own job to keep clear of the machinery. They're busy, and they have work to do.

You leave the house with one pair of boots and all the clothes you'll need all day -- for the freezing weather, the walk that warms you up, the overheated apartment you visit, the underheated office you work in, and the chilly subway station. Clever layer applications help, but patience (and an extra pair of socks in your coat pocket) works best.

Slush comes in white, gray, black, and two browns, wet and dry. Icee slush looks (and probably is) exactly the consistency of a frozen soda pop. A big bootsplash directly into slush looks like fireworks.

Walks take extra time not because you have to work through deep snow or have to avoid impassable banks or get lost because pathways clearly on your map simply do not exist in snow, though all of that is true.

Walks take extra time because you just keep stopping to look at stuff. Icicles caused by ice dams; houses turned magical by feet of snow. The sound, when it gets one magical degree colder, of snow suddenly starting to squeak; the view up or down an environment ineradicably changed, in a way that makes you never want to forget what you see.

And above all, there is watching snow in streetlights. Squadrons of snowflakes dipping and circling through the cone of light thrown by a streetlamp are the built environment version of the Northern Lights -- limitlessly watchable manifestations of the silent mysteries of night time.

In Cambridge, as annoying and frustrating as, literally, foot after foot of snow could be, I got to stand and watch snow come down through a streetlamp. I'm sorry Lawson never did -- I would love to have his perceptions.

I hope you all get to do the same.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed