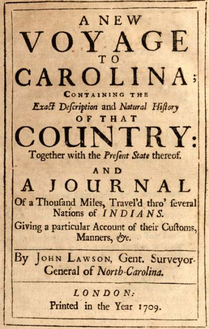

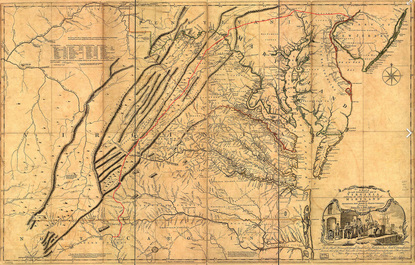

Lawson's journey, which we will be retracing beginning October 12 in Charleston, was transformational for him, for North and South Carolina -- and for the original inhabitants of those states. The native population had been much transformed in the decades before Lawson arrived, and that transformation included the death by disease of most of the Native Americans and the enslavement of many others. Lawson himself says that "The Small-Pox and Rum have made such a Destruction amongst them, that, on good grounds, I do believe, there is not the sixth Savage living within two hundred Miles of all our Settlements, as there were fifty Years ago. These poor Creatures have so many Enemies to destroy them, that it's a wonder one of them is lest alive near us," and he doesn't even bring up the nasty habit of the European settlers of selling the Indians into slavery -- by 1720, of a colonial population of about 17,000, some 1,500 (about one in 11 people) were Indian slaves. Though the Indians themselves practiced slavery, at some point a people is going to say "enough is enough," and Lawson not only helped bring about the event that pushed the Tuscaroras to the limit and started the Tuscarora War, he turned out, quite accidentally, to be the first target of their wrath. The description that follows is largely distilled from the excellent "Among the Tuscarora: The strange and mysterious death of John Lawson, gentleman, explorer, and writer," from the North Carolina Literary Review.

In his descriptions of Indians Lawson was one of the most thoughtful and understanding of European observers. In the end it didn't help.

In his descriptions of Indians Lawson was one of the most thoughtful and understanding of European observers. In the end it didn't help. They are really better to us, than we are to them; they always give us Victuals at their Quarters, and take care we are arm’d against Hunger and Thirst: We do not so by them (generally speaking) but let them walk by our Doors Hungry, and do not often relieve them. We look upon them with Scorn and Disdain, and think them little better than Beasts in Humane Shape, though if well examined, we shall find that, for all our Religion and Education, we possess more Moral Deformities, and Evils than these Savages do, or are acquainted withal.

Even so. More and more settlers came; those that came shared drink and disease and enslaved their children.

The Tuscarora saw where this was all leading and tried to move away: in 1710 they applied to the governor of Pennsylvania for amnesty in one of the most hearbreakingly plaintive letters of all time, saying they wanted to get away from the North Carolina settlers, requesting among other things that for their children "Room to sport & Play without danger of Slavery, might be allowed them" and, for the people in general, "to intreat a Cessation from murdering & taking them, that by the allowance thereof, they may not be affraid of a mouse, or any other thing that Ruffles the Leaves." The government of Pennsylvania, cautious, said they were welcome so long as they could provide a testimonial to their good behavior from the Carolina government.

No such recommendation came from North Carolina.

Unable to stay and with nowhere to go, in 1711 the Tuscarora determined to fight back, choosing September 22 as the day for their attack. A week or so beforehand, Lawson and von Graffenried and a small party sallied upstream on the Neuse River, hoping to find a good route to trade with the Colony of Virginia. One of their scouts stumbled into a party of the Tuscarora, who then surrounded Lawson's party.

Lawson, known to them certainly as one of the fairest of their partners, was also a man who brought more and more settlers, founding towns for them to live in, to disastrous effect. Von Graffenried describes Lawson arguing with the Indians, though about what he doesn't say. His account is staggeringly self-serving, blaming Lawson for everything from their capture by the Tuscarora to the decision to settle in Carolina in the first place.

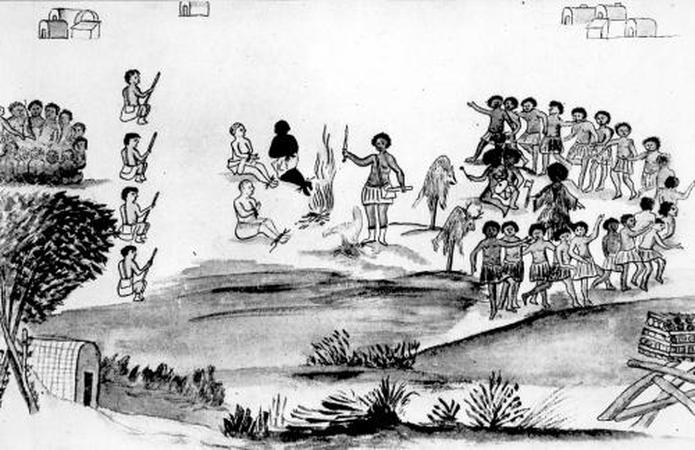

The Tuscarora killed Lawson, either by slitting his throat or, perhaps, in a fashion Lawson had himself described: The Fire of Pitch-Pine being got ready, and a Feast appointed, which is solemnly kept at the time of their acting this Tragedy, the Sufferer has his Body stuck thick with Light-Wood-Splinters, which are lighted like so many Candles, the tortur'd Person dancing round a great Fire, till his Strength fails, and disables him from making them any farther Pastime.

Von Graffenried stayed captive for weeks, forced to, in the words of Marjorie Hudson, "watch helplessly as warriors headed out to massacre his Palatines, bringing back captives who told him the grisly details — women impaled on stakes, more than 80 infants slaughtered, more than 130 settlers killed. New Bern was almost wiped out."

Six weeks later von Graffenried -- appropriately traumatized, it must be said -- was set free, and he eventually wrote his account blaming everything on Lawson. Lawson was the first to die in the Tuscarora War, but in the end the settlers had numbers. The Tuscarora War lasted two years. At the end virtually no Tuscarora remained in Carolina.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed