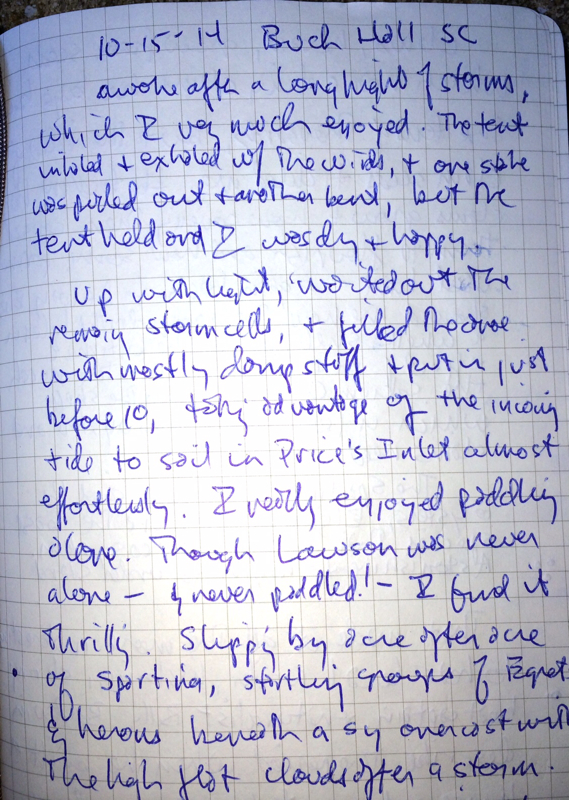

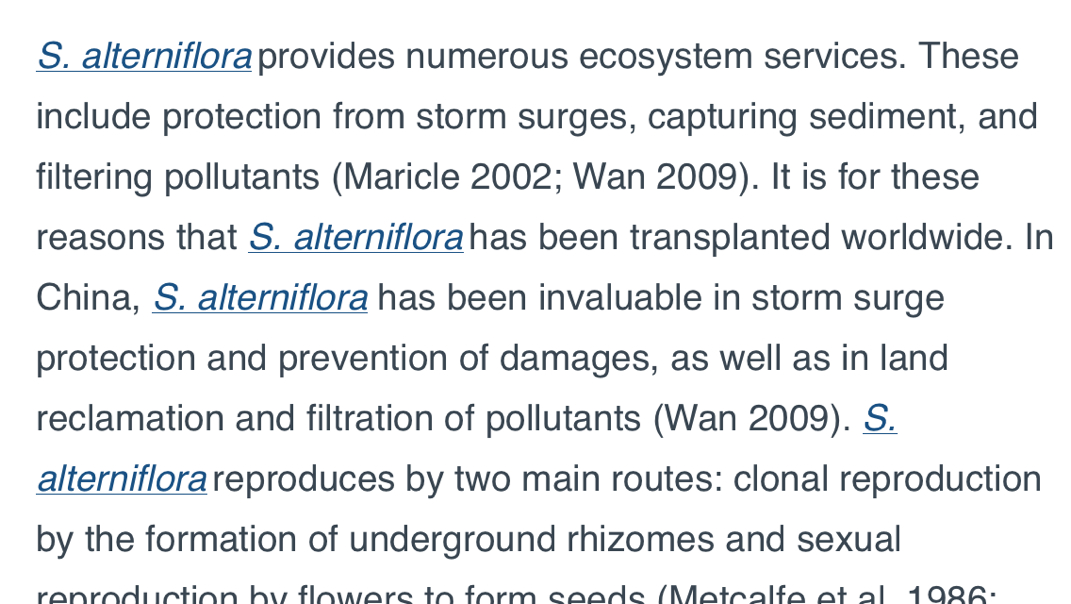

Not regular grass -- with marsh grass. Cordgrass, you might call it, but the naturalists call it Spartina alterniflora, and as we paddled by acres and acres and acres of it my guide Ed Deal told me he thought it was one of the most important plants in the world.

After research, I agree.

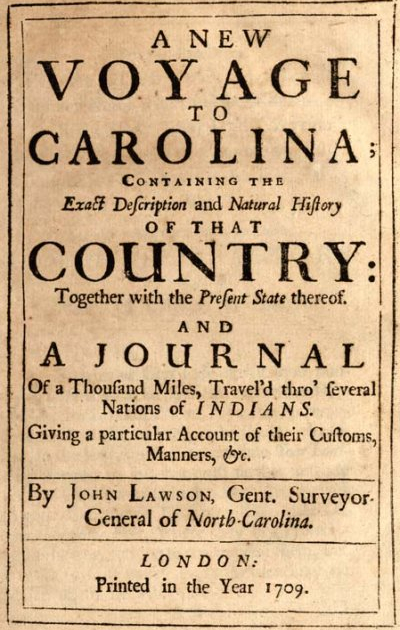

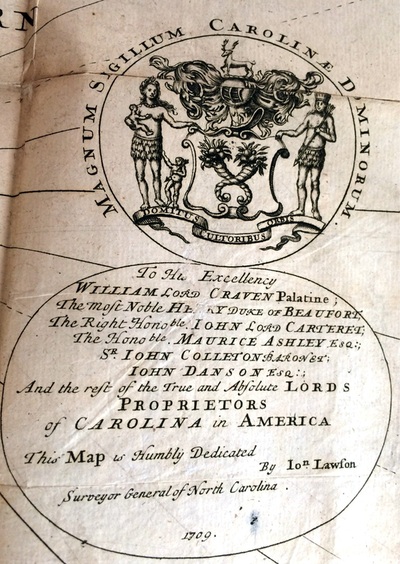

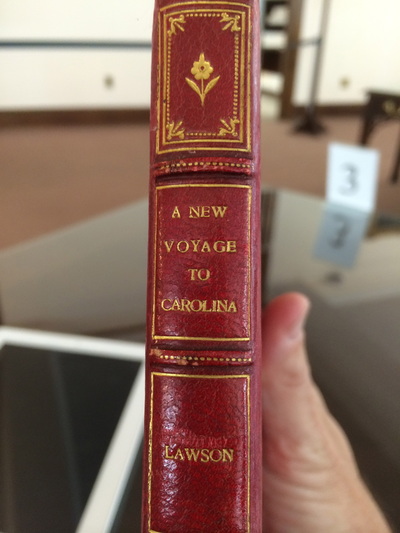

When I spoke with James Morris, director of the Baruch Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences at the University of South Carolina, he told me the salt marshes I’d be paddling through would be very much like the ones John Lawson had paddled through in 1700. “Much of the South Carolina is unspoiled,” he said. “South Carolina is unique in that regard in that we have so much protected coastline.” Long before slaves would have cleared the tidal swamps and freshwater marshes for the rice and indigo plantations that made South Carolina rich, in 1700 “it still would have been really, really wild.” And whereas freshwater marshes, further in on the coastline, are riots of different plant species, the salt marshes are “monospecific,” Morris said.

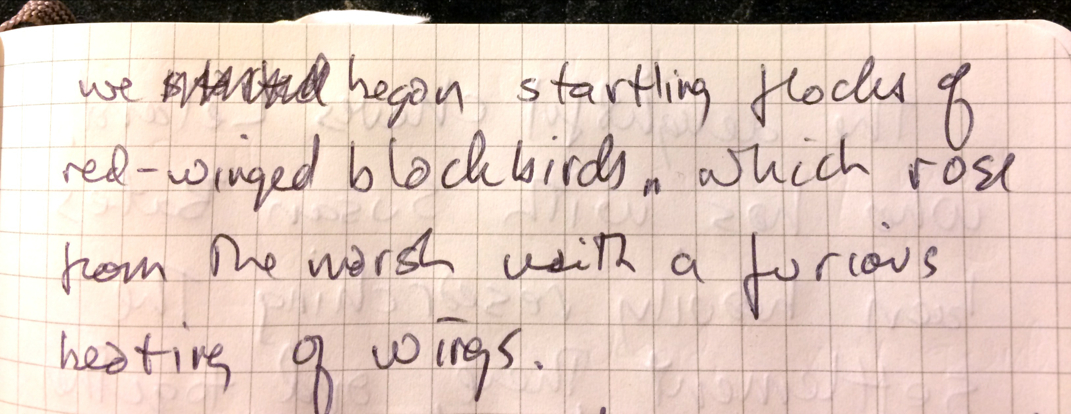

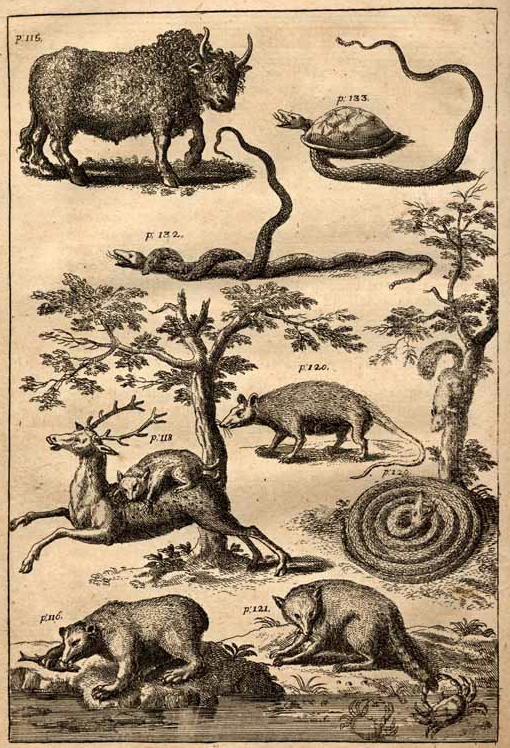

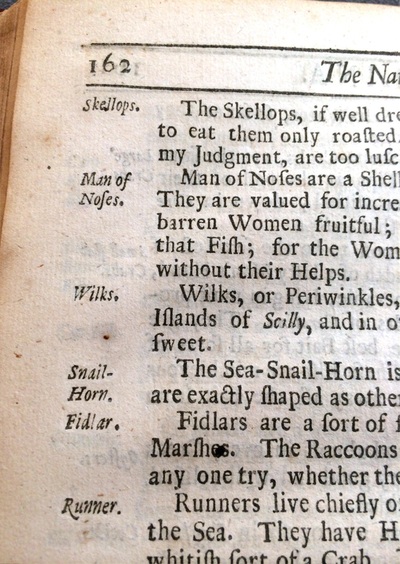

| They’re spartina alterniflora, and that’s about it. “He would have smelled rotten eggs,” Morris said. “You’ll smell it too. That rotten egg odor is hydrogen sulfide, and it’s a natural byproduct of the decay of leaves and roots in a salt marsh marine environment.” I smelled it. To me it smelled great. Here’s the story. Spartina does an amazing thing: It creates its own freshwater to live. Designed to prosper in the tidal zone where sediments accumulate and sea and soil meet, it has learned to excrete excess salt, not only making it able to withstand the salty tidal water but making it attractive to species like periwinkle snails, which come by to lap up the delicious minerals the Spartina doesn’t want. The snails, using rows of replaceable hooklike sharp teeth in a mouthlike thingy called a radula also help to decompose the dead Spartina. egrets (snowy and great), ibises, oystercatchers, black skippers, black skimmers, bald eagles, osprey, willets, short-billed dowagers, the not-quite-as-endangered-as-it-used-to-be brown woodstork, and an enormous variety of gulls and the plovers, sandpipers, and sanderlings that, like grandchildren, even guides can’t always tell one from another (though my guide Elizabeth Anderegg pointed out spotted sandpipers, identifiable by their stuttery wingbeats: b-r-r-r, coast; b-r-r-r, coast). Elizabeth even pointed out a pair of roseate spoonbills, who were just then coming in on their migratory path. Elizabeth also explained why the double-crested cormorants we saw tended to stand stoic atop pier pilings, wings open, as though doing sun salutations or posing for a “Karate Kid” poster. The cormorant’s feathers are not particularly oily, she says -- this gives it less buoyancy and enables it compete by diving deeper for fish. But that means the feathers get wet, so the fish is heavy and needs to dry off before it can again fly well. If we came upon one not yet dry, when it flew away from us it sank right to the surface of the channel, where -- whap! whap! whap! -- it patty-caked its feet along the surface until it had enough speed to rise. | The dropping down of little fragments of dead Spartina called detritus begins to create mud, which of course becomes matrix for more Spartina, which spreads through long, hollow rhizomes. What’s more, the marsh also attracts diatoms and other phytoplankton, which when the tide goes out form a surface scum that helps stabilize the mud, further encouraging Spartina growth and providing habitat and food for things like snails, oysters, and clams and other filter feeders, to say nothing of the fiddler and ghost crabs that all but cover the shoreline. All together those animals form the base of an incredibly rich habitat. The Spartina stabilizes the shoreline with its rhizomes, allowing oysters to get -- literally -- a foothold. Between the Spartina and the oysters the water is cleaned and the habitat improved. Many fish -- my guides loved to point out mullets and menhaden -- love the cover of the Spartina, especially for juveniles. Oysters mean more oysters, and the oyster shoals their shells create further stabilize the coastline. Sponges come along and eat the whelk, snails, and other invertebrates by drilling into them (those tiny holes you see in found shells? Spongesign.), after which the shells slowly dissolve back into the water, their calcium carbonate just what new baby oysters need. Nothing wasted in the Spartina. Lots of little fish equals lots of big fish who like to eat them and lots of shorebirds who like to eat the big and little fish. In one five-day period I saw brown pelicans (who live there, and white ones, migrating through), herons (great blue, little blue, and tricolor), |

Go further in towards shore and you get smaller Spartina (less able to grow above the tide), then black needlerush and goldenrod and other plants more suited to brackish or freshwater. Trees like loblolly pines and holly, yaupon and salt cedar and of course the omnipresent palmetto, which Lawson said grew so slowly that you couldn’t chart its progress in a single lifetime. Not quite, say the locals, but they are slow.

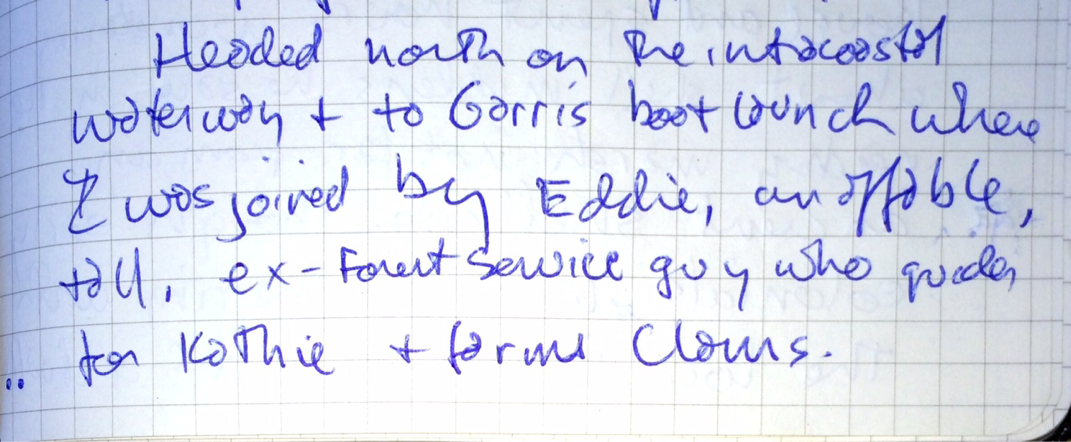

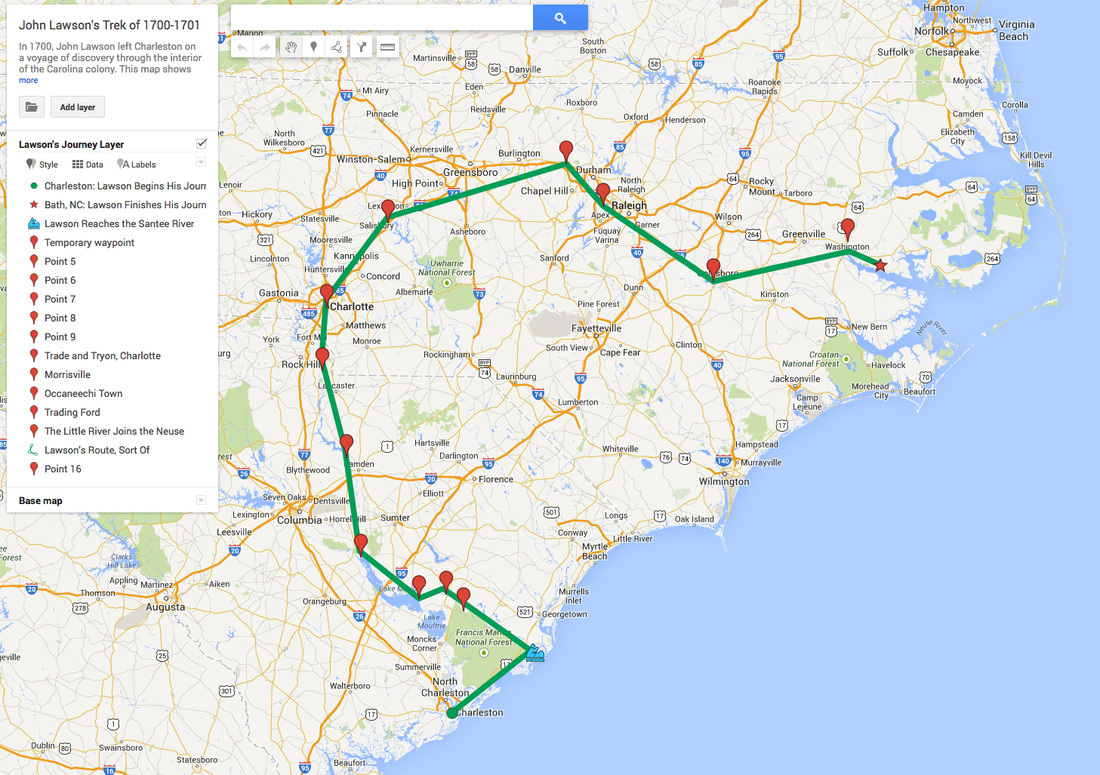

Lawson found the salt marsh almost not worth describing. He never mentioned the grasses, but then again he barely mentioned wind and tides either, so he was just paying attention to other things. In response to Morris’s note that the salt marshes hadn’t changed much in 300 years, Ed Deal said, “well, you are taking a shortcut.” Referring, of course, to the Intracoastal Waterway, the series of bays, channels, and canals partially natural and partially artificial that’s been growing since the early 1800s. So once I paddled across Charleston Harbor, I did not have to paddle to the ocean side of Sullivan’s Island and then ride the tide in through an inlet called “the Breach” (“At 4 in the Afternoon, (at half FLood) we pass’d with our Canoe over the Breach”), which the locals say is treacherous at best. (British troops tried to cross it during the Revolutionary Battle of Sullivan’s Island and failed.) Instead we crossed the harbor, took a left, and could have paddled pretty much straight for 40 miles or so to the mouth of the Santee. Very different from the tidal creeks and inlets that Lawson described as “the most difficult Way I ever saw, occasion’d by Reason of the multitude of Creeks lying along the Main, keeping their Course thro’ the Marshes, turning and winding like a Labyrinth, having the Tide of Ebb and Flood twenty Times in less than three Leagues going.” And I will say as beautiful as I found the grasses along the waterway, when I paddled along inlets or up creeks, in their winding silence I felt like I was truly seeing nature at her ease, going about her business as she had done for centuries. Nature, as it were, in her housedress.

For now though, at least along the South Carolina coast I traversed, protected by the Francis Marion National Forest and the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, my beloved Spartina has someone to look out for it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed