| We cannot get away from ourselves. Camp in the savanna and look up at the contrails. Hike the trail by GPS. Climb the mountain and get better reception. You probably got there in the first place following the advice of a way-finding system accurate to the capacity of saying, “The OTHER side of the street, you idiot.” Or maybe you referred to a map that you bought in easily obtainable staple-bound book form at any number of places within a five-minute drive from your house. Or, if that wasn't satisfactory, you went to an office in a state government building and bought a USGS topographical quadrant map that gives you so much detail about your terrain that you know not only every ten-foot change in elevation but every building on every lot, down to sheds and outhouses. And that's all good: Google Maps can show you everywhere on the planet; Wikipedia shares information on every place and culture. But no doubt this rising tide of information can feel a bit overwhelming. No surprise, then, that the days when there were still holes on the maps—when uncertainty still held a post of honor—seem attractive. "I accidentally met with a Gentleman, who had been Abroad, and was very well acquainted with the Ways of Living in both Indies," Lawson says in A New Voyage to Carolina, the book that a decade later resulted from this chance meeting. "Of whom," he goes on, "having made Enquiry concerning them, he assur'd me that Carolina was the best Country I could go to; and, that there then lay a Ship in the Thames, in which I might have my Passage. I laid hold on this Opportunity, and was not long on Board before we fell down the River, and sail’d....” And now you know almost as much as anyone else in the world about the beginning of Lawson's remarkable journey through what is now North Carolina and South Carolina. The two-month journey produced a book of incomparable observations about the Carolina land, inhabitants, flora and fauna; a map that is widely known, if not much of a cartological advance; and a personal story of adventure and tragedy that ended in 1711 with Lawson’s death at the hands of the native people he had befriended. I stumbled onto Lawson's tale the way most Carolinians do: I wanted to know more about where I was. Interested in the history of my own little piece of ground in Raleigh, I first tried to trace its deed backwards only to quickly land in an insoluble tangle of developers selling it back and forth. So I thought I'd start from the various piedmont Indian tribes, who owned it in 1663 when through the Carolina Charter King Charles II of England first granted it to the eight Lords Proprietors. No luck, but I learned about Lawson’s journey and thought it might hold some clues. |

Either this is the only existing portrait of John Lawson or there isn’t one. It’s the right time period, the right attitude, the right name, and the right artist, but questions remain (for example, Lawson was never knighted, but the portrait’s history identifies him as “sir”). From the private collection of Elizabeth Sparrow. Used by kind permission.

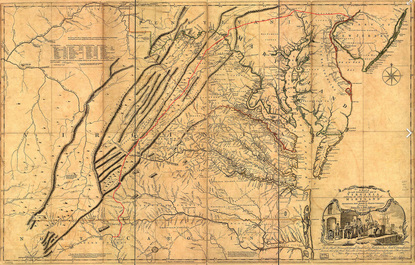

Imagine young John Lawson. In 1700 Lawson was 25, and the well-educated, well-connected son of a physician drifted in London like any young man in any age, searching for a way to make a name for himself – looking for something to do and a good reason to do it. Fascinated by the scientists of the new Royal Society who met at Gresham College in London, where Lawson had attended lectures, Lawson yearned for adventure, accomplishment, notoriety and gain. Which is to say, Lawson was a young man, and it’s easy to understand his interest in the natural world, in science, in discovery. Hooke, Wren and Halley had made the famous coffee house wager that caused Isaac Newton to write his Principia Mathematica barely 15 years before; it was published when Lawson was a teen. The best map of North America looked like an unfinished child's drawing. DeSoto had wandered and died in the southern region of the modern day United States a century and half before, but little mappable knowledge had emerged from his enterprise. LaSalle had done the same around the Great Lakes and Mississippi River during Lawson's childhood with much the same result. So it hardly surprises to learn that when Lawson considered attending the Grand Jubilee in Rome (it was a big deal, a celebration held every quarter century, and honestly, it was something to do) it took only a casual conversation to quite literally turn him around.

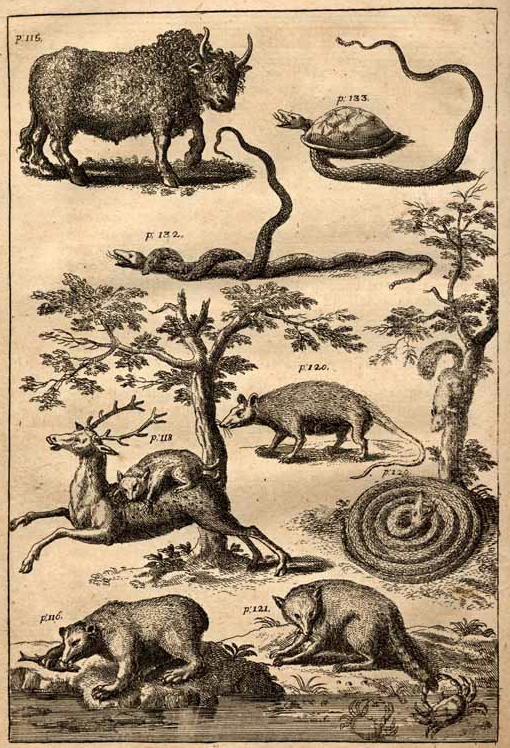

Lawson saw a lot of cool animals. He describes the turtle grabbing the snake and pulling its head in, the snake killing another snake, and the raccoon going crabbing, using its tail for bait. We don’t think Lawson drew the pictures. Source: North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

|

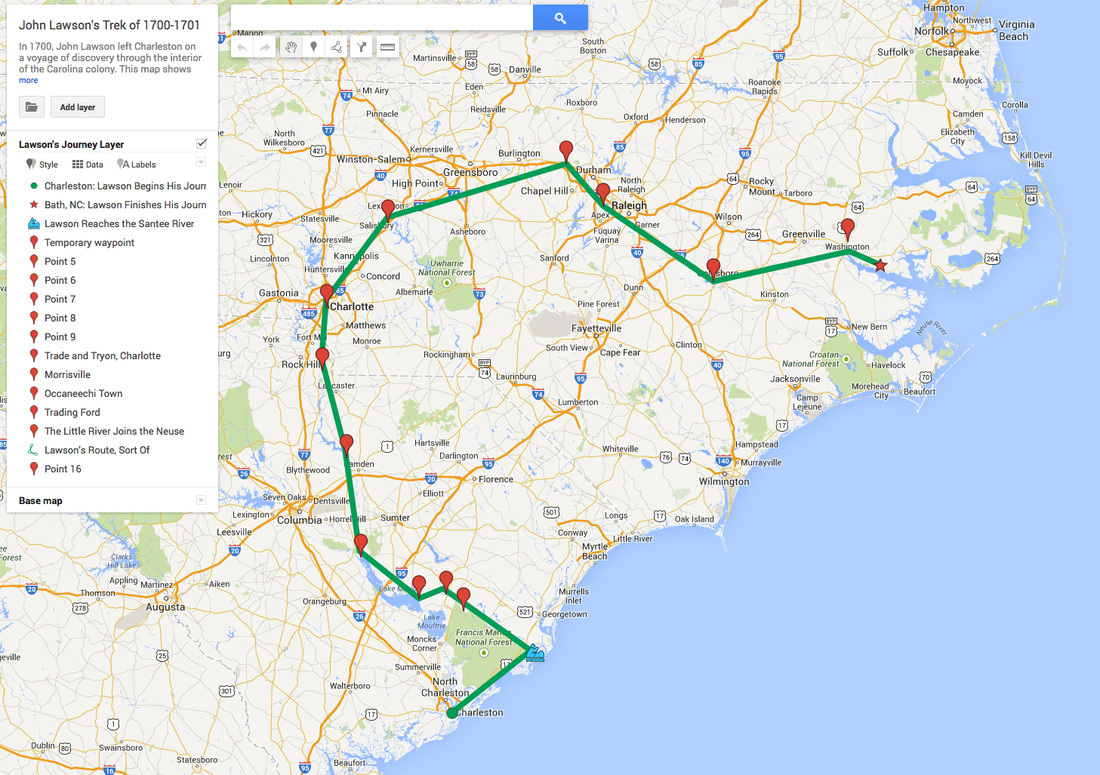

By 1670 the British had planted a colonial city in Carolina: Charles-Town, on the Ashley River. It moved in 1680 to Oyster Point, the spit at the Ashley’s confluence with the Cooper, which made for a more convenient—and not coincidentally defensible—base. Earning its name in the Civil War, the bottom of Charleston is to this day a defensive seawall called the Battery. Lawson certainly sailed there in 1700, and on December 28 of that year certainly set off on a journey, first by canoe and then on foot, that over the subsequent months took him through much of what is now the Carolina interior. Whether he set off because the Lords Proprietors suggested he do so, or because it seemed like something interesting to do, nobody can say for certain, though people have strong opinions on both sides.

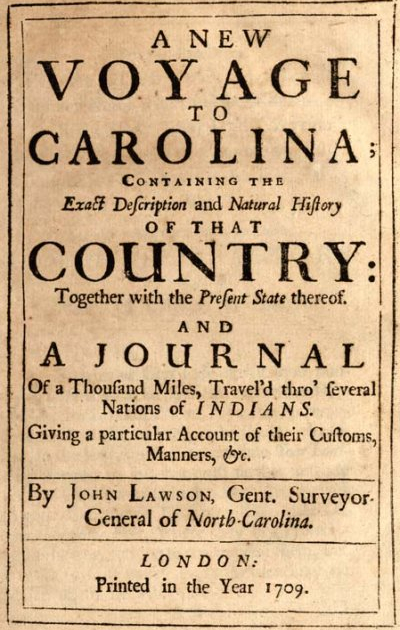

What nobody disagrees about is the record Lawson left. Lawson spent the better part of the next decade collecting horticultural specimens, developing land, surveying and learning about the Native Americans. Along with a detailed journal of his long walk, the book Lawson eventually created includes an entire natural history of Carolina, listing plants, animals and native tribes and describing the terrain, rivers and settlements—native and colonial—he encountered. Lawson was above all a model of 17th-century science. He observed and gave full voice to what he saw, regardless of how it squared with what he expected. The book has been called “one of the best travel accounts of the early eighteenth-century colonies.” In an unpublished paper archaeologist Stephen Davis of the University of North Carolina says its significance comes from being, “the first book to provide a detailed, clearly written description of the backcountry, including its fauna, flora, geology, topography, and people.”

Lawson, that is, had his eyes open. Unusual among explorers of the time, Lawson understood he was seeing not a virgin continent, but rather the ragged end of a devastated great civilization, ruined by disease, alcohol, slavery and displacement. He described simply what he encountered, and his record is all the more vital (“uncommonly strong and sprightly,” another historian called it) for its honesty.

Since nobody has ever retraced Lawson’s footsteps, I plan to do exactly as Lawson did. Not just to slavishly retrace his path, but to look around with eyes wide open, trying to leave preconceptions behind and, with the help of historians, geologists, biologists, adventurers and ecologists, record what has changed in 300 years and what, in another 300 years, those who come after might find valuable to know.

Comparing today to the past is foundational to science, and we do it all the time. Recent years have seen scientists return to the observations of Thoreau to document the effects of climate change by comparing the dates of the blossomings and migrations he saw to our current observations; to the works of environmentalist Aldo Leopold to document what he would have heard (Stanley Temple has tried to recreate the sounds he would have encountered in the morning); to the Grinnell-Storer transect of Yosemite to see how the animal populations have changed in the century since the original observations. Climatologists have for years been returning to ships' logs to gather data from centuries ago about wind, temperature and current.

I hope, with help from scientists and other observers (and support from the Knight Science Journalism Fellowships at MIT), to add in a small way to that scientific enterprise, and I’m preparing by learning what I can. But I hope much more simply to add to the conversation by seeing, by spending my months in-country as Lawson did, observing what I see rather than what I expect, and hopefully getting people who understand it—scientists, historians, natives, locals—to help me understand. I’ve begun a website, and I’ll update the blog regularly; I’ll post on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. I think Lawson would have done the same had those tools been available to him.

I like to think of the properly observed life as living as though you were on your junior year abroad, when the kind of ticket you get for the bus, the smell of the funicular railroad, the food a vendor sells, is not just the daily detail you pass by. It’s the essence of life. It’s what the people eat, how they get around, how they adapt to hillside, shoreline, riverbank. It’s what you’ll remember and what you’ll tell other people. I think we should live our entire lives paying attention to things like that.

Lawson did. Lawson, a scientist at heart, consciously opened his ears and allowed the universe to whisper to him, and as a result he documented, perhaps better than anyone else of his time, a world that within a few decades had all but disappeared.

With a changing climate and rising seas, our own world may be about to undergo radical change, so it seems appropriate to head out to document it. For my first segment of this trip, like Lawson, I’ll paddle by canoe from Charleston to the mouth of the Santee River and upriver a day – about 50 miles in total. Like Lawson, I’m depending on the kindness of strangers and the guidance of locals.

There are no holes in the map anymore. The holes in our understanding, however, remain. So we go out into the field and hope to fill those.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed