I spent my last trek focused on Lancaster, SC, where the Native American Studies Center of the University of South Carolina-Lancaster was holding, coincidentally, its annual Native American Studies Week, and the Lawson Trek got to play. As ever, I'd rather be lucky than good. I'll tell you about that soon, and about the welcome I received (again, like Lawson) from the Catawbas themselves.

| But I was talking about land. Walking north out of Camden left no doubt we were in the midlands, the Piedmont of South Carolina. In Camden we had noticed that the walk into town from the south had been almost completely flat but that the walk out of town to the north had enough rolling hills that you might not notice them as you walked but you would notice morning fog settling in the low places. We saw the land shift from pure loam and clay to rock, which was most notable in the copses of trees surrounding rocks too big for farmers to clear that pop up in the middle of the pastures for beef cattle that now have joined the cotton and soy fields and the pine farms we pass by. In fact, we now regularly pass by enormous boulders, which just like the lay of the land help determine the land's use. Not for nothing is Camden the beginning of horse country. |

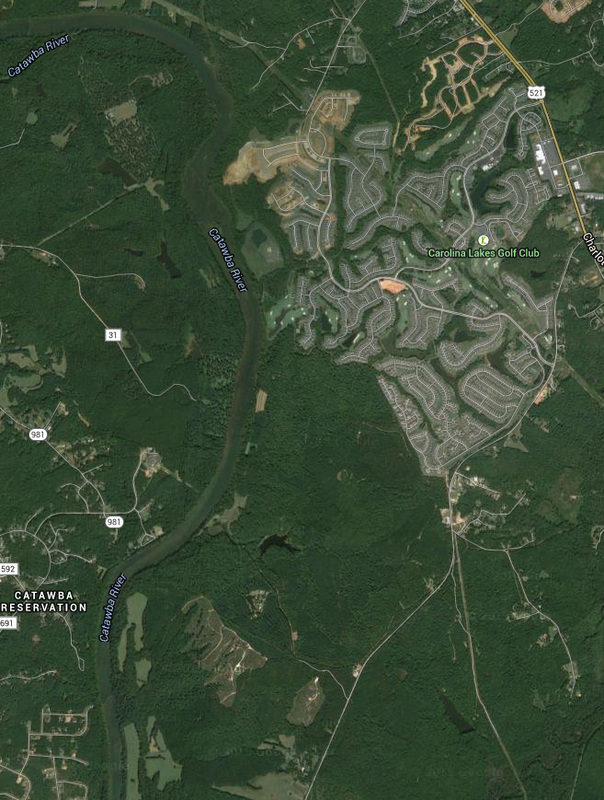

| But for the clearest indication of how a culture has changed is to look at what's come next, and the place to do that is The Ivy Place, a few miles up the Catawba River from Lancaster. Built in 1850 by one Adam Ivy, Ivy Place is still owned by the descendants of James Nisbet, a New York physician who had grown up in the area and bought the house as a homeplace in the 1880s. But the Ivy Place has more than just that beautiful 1850 house, barns, pick-your-own strawberry patches, and a great facility you can rent for weddings. It also has a future as open land. Because its owners have placed a conservation easement on it through the Katawba Valley Land Trust, the Ivy Place will never be developed. It will continue to be a working farm, and the family will own it, use it for its own purposes, farm strawberries and pine trees and beef cattle, host events -- but the land will never be developed. If you want to know what that means, look to the right. On the lower left of the image is the Catawba Reservation; across the river is Ivy Place and other land owned by the Nesbit family. North of that is what happens to land without conservation easements. |

Which was why Jimmy was so pleased as he showed us the territory his family owns (and even some his family sold, though with easements on it protecting the river). Until the late 1950s the Catawbas operated a one-car ferry where route 5 now crosses the river, but the new road ended that. The more than 3 miles of riverside the Nesbits own at least give open land a fighting chance. Jimmy walked us to a site that had once been a Catawba town, and doing nothing more difficult than idly kicking around dirt he unearthed 18th-century pottery fragments that he gave to me -- a connection with centuries past.

Not that the land as it is now, with lovely second-growth forest and old mills and town sites and such, would have been as it is now when Lawson passed. "The coastal plain would've been magnificent longleaf pine forests," Barry reminded us, as we followed old Waxhaw paths and double-tracks as old as horse and buggies along the conserved land.

After all, you need somewhere to dock your kayak when it's time to gather the basketballs.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed