|

I recently did, on the Lawson Trek, something I've wanted to do my whole life: I walked for a day until I was tired, and when weariness and exhaustion came upon me, I spent my last mile looking around. I eventually found a pleasant, secluded spot where I could see I was bothering nobody, disturbing neither crop nor yard, visible from neither home nor road. In a copse of pines I set up my tent in the dusk. Then I ate, then I slept. When I woke, I packed up and was on my way. I had no idea on whose land I had slept; I asked no permission and I begged no forgiveness. By day I walked the earth; at sunset I lay down upon it; at dawn I arose from it and walked on. The response I've received as I've told people about that one-night adventure shows me how much this trek -- like Lawson's -- is about the land, and who owns it and is allowed to use it and for what purposes. One person who heard about my decision to sleep right on a piece of unused ground in a cluster of pines was so affronted that she instantly refused my request to walk across hers. This land business? It's powerful stuff. One of my many friends in the small burg of McClellanville, north of Charleston, quoted another friend, speaking of Lawson and his unpleasant death at the hands of the Tuscarora a decade after his journey. "He was a land developer," my friend quoted his friend. "And he got what they all deserve." And to be sure, at the base -- literally -- of Lawson's journey was land. What kind of land was Carolina? Who lived there? Who owned it? How could colonists get it? How and where could you cross it? What were the obstacles? What grew there now, and what would grow there under ideal (read: English) stewardship? That's nothing like an exaggeration. Lawson describes one area he sees as "curious dry Marshes and Savanna's adjoining to it, and would prove an excellent thriving Range for Cattle and Hogs, provided the English were seated upon it." He admires the Indians, and he's often very critical of the way they're treated, but Lawson says stuff like this a million times, and I quote it just to remind you: yes, Lawson was interested in the science and the anthropology and the botany and all the other wonderful stuff on his wonderful adventure, but he was also interested, like every single colonist to North America, in land, and in getting it away from its current inhabitants. Land acquisition was what was going on, and however much we admire Lawson's admiration for the Indians and his curious and questing spirit, he was involved in the same continental land-grab everyone else was, and he could see as well as anyone else how that worked out for the current occupants. "These Sewees have been formerly a large Nation," he says of his first Indian assistants, "though now very much decreas'd, since the English have seated their Land, and all other Nations of Indians are observ'd to partake of the same Fate, where Europeans come." That was kind of new for the Indians. Not that they didn't have boundaries and territories and markers and all that, but people -- especially people of the same group -- were expected to move about the land, and the idea that one would not have been allowed to cross and seek shelter would have bordered on the absurd. "This night we got to one Scipio's Hutt, a famous Hunter," Lawson says somewhere among the Santee Indians. "There was no Body at Home; but ... we made our selves welcome to what his Cabin afforded, (which is a Thing common) the Indians allowing it practicable to the English Traders, to take out of their Houses what they need in their Absence, in Lieu where of they most commonly leave some small Gratuity of Tobacco, Paint, Beads. &c."

Mind you, when land is posted -- or trees are decorated with purple stripes, which is the equivalent of 'No Trespassing' signs -- the Lawson Trek does not cross. That said, when the Lawson Trek finds itself lost, or misguided, or confused, if the solution to a problem appears across a field or or other small parcel of even posted land, I do not hesitate to allow common sense to outweigh the sanctity of private property. Again: laying down where I found myself when energy and sunlight diminished was a longstanding goal of mine. I can remember as long ago as early childhood, when during family car rides I would imagine walking instead of driving, and the idea of setting out cross-country first began to attract me. I thought about the obvious utility for camp shelter of those little clumps of trees near highway exit ramps; I looked at the borders of trees along roads, separating farmed fields from the highway and thought the same. To me, walking along until it was time to rest, and then resting until it was time to walk again, seemed exciting and humane and fundamental. And I know that those childish thoughts need to coexist with individual property rights. And a cool study shows that even people who post their property will allow people to hunt it almost half the time; they just want you to ask permission. Which is totally reasonable. And were I going to make a common practice of just laying down where I found myself I would expect, sooner or later, to offend the actual owners of the land on which I lay, not another landowner on their behalf. And part of what I'm doing as the Lawson Trek makes its way across the land is finding out not just what it feels like to walk the earth (it feels great!) but to see what it feels like for others when we show up, like Lawson did, and need to eat, or sleep -- or park a car or use a restroom or get a ride to Pack's Landing. So far we've almost never been denied permission to walk, rest, or sleep, but it's a complicated world. Some churches have opened their chapels for us to sleep in; others have denied our requests to camp on a corner of their land. Most people meeting us seem cheerful, and when they learn of our project are delighted to share

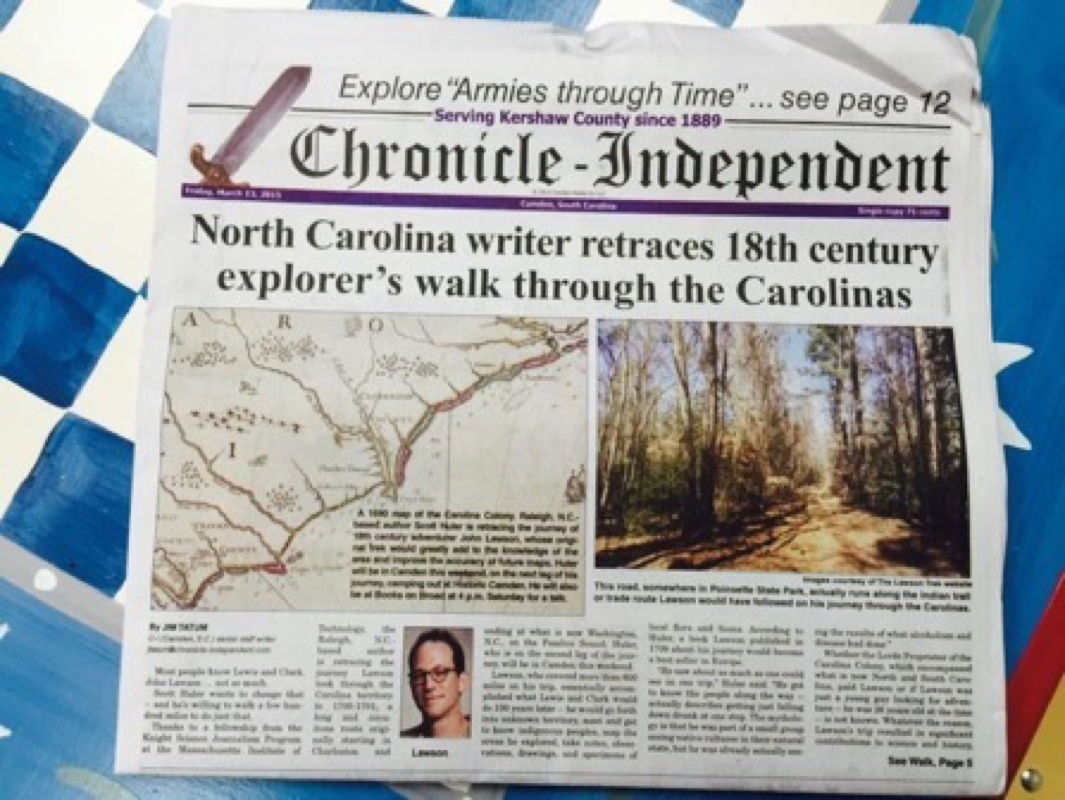

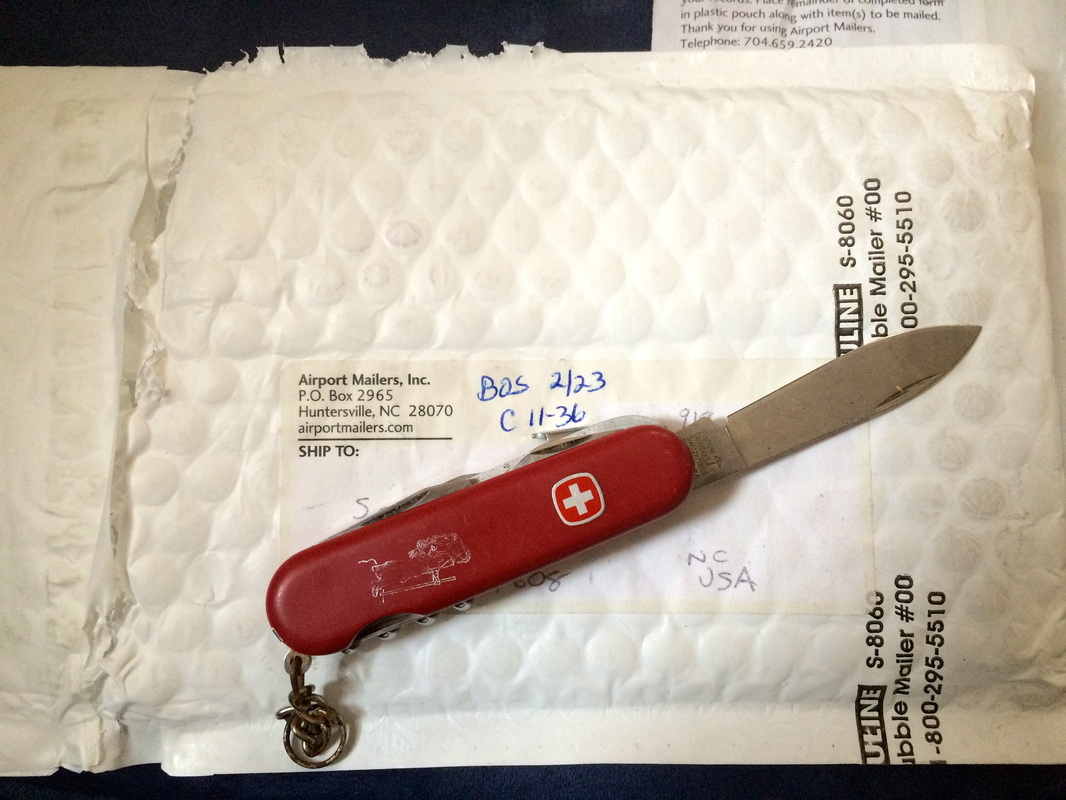

So anyhow we drove down to the little town of Horatio, where we ended the last trek, and I and my two partners (my friend Michael and my ecologist Katie Winsett, joining the trek for the second segment) set out north, towards Camden. The first thing we learned was that the Camden Chronicle-Independent, through the excellent work of reporter Jim Tatum, featured the Trek -- on the front page. Above the fold, no less. You need to be a subscriber to read it online; I'll see if I can't get permission to reproduce it here though. The next thing was I got to introduce my friends to the Lenoir Store, open since at least 1808, which is one of life's great treasures; I would link to my post about it, but the Weebly app for the iPad is insane and I can't do that. Scroll down and you can easily find it. Michael took this awesome panorama of the store. We walked today along the backroads that trace what would have been the trail highway serving the Indians of the Mississippian period. We visited the little town of Boykin, where we met broom-maker Susan Simpson, who's been making brooms for 45 years and who reminded us that we see a church every couple miles along the road not because people can't agree on which church or demonination to support but because when the churches were founded people had to walk there. So more than 5 miles between churches was a hardship. An amazing insight that I've totally missed until this point. Boykin was settled in the 1740s (Simpson's broom shop is in a slave cabin from that period), but Camden, where we are staying the nights this trek in the Kershaw House (rebuilt and modeled exactly after a house left standing during the Revolution but burned during the Civil War), was the first inland town in South Carolina, settled in the 1730s as one of the townships along the rivers designed by the King to help the settlers expand out of Charleston and gather more of the best land for themselves. We are guests of the delightful Historic Camden; in addition, we'll have a nice meetup at 4 pm March 14 at Books on Broad. Newspapers, historic lodging, and bookstore hospitality -- Camden is treating the Lawson Trek well indeed. The highlight of our day's walk today was several abandoned houses along our way. Lawson describes seeing abandoned homes and villages and he understood that he was traveling through an Indian culture that was reeling from the devastation of disease, rum, and displacement. In many ways we travel through a similar landscape, 300 years later -- a place of sometime abandonment, reeling from the effects of industrial farming and globalism. In town after town we meet people who tell us that the majority of their residents are retired; there's nothing to keep the young people around. Farms are often financially impossible to maintain for families, so enormous corporations control the land. Simplistic to be sure, but the fact is as we walk these rural roads, as we visit these small towns, we cannot fail to feel that we are witnessing a culture reeling from blows it has not weathered well. Here is a sampling of only a few of the abandoned places we visited today. So my pocket knife has returned, and as I fondly caress it, as I hold it to my cheek and murmur "poor baby," I yield to relief that the difficulties I faced in its absence have ended. I best remember sitting by the side of the road, trying to saw through a piece of lunchtime pepperoni with the dull replacement, and with each sawing motion I repeated: “Fuck -- the -- fuck -- ing -- T -- S -- A -- (breath) -- Fuck -- the -- fuck -- ing -- T -- S -- A.” Because I was sawing through the pepperoni with my crappy backup knife because my regular knife was en route to me somewhere, probably. I had mailed it back to myself -- perhaps the tenth time I have performed a variation on this idiotic gavotte -- from Logan Airport in Boston, where I was stunned to find it in my shoulder bag. It had slipped through the screeners on the outbound from Raleigh-Durham, where I live, so I found myself having to cope with it at an away airport, where I haven’t chosen a spot to secrete it if it accidentally makes its way to the airport with me. That I had to send my usual camping knife back was a rarity; usually I transgress with my little multitool, which includes a scissors and a tweezers and is engraved with the date of my best friend’s marriage, a groom gift from that event. It hangs on my keyring. I had prided myself on finally learning to remove it before flights, but then I immediately began forgetting to put it back on, which led to a lot of wasted moleskin on a previous trip, when in the absence of its scissors we had to cut out blister treatments with a sharp pocket knife. That went even worse than the pepperoni. You might still believe this all has something to do with protecting ourselves from terrorists, but if you think that you’re a fool. In 2013 the TSA floated the idea of allowing people to carry their tiny little personal tools with them on airplanes but the flight attendants -- among others -- want mad. I wasn’t surprised -- a flight attendant I know, when I loudly scoffed at TSA protecting us from our tools, told me she thought allowing passengers to have sharpened implements would cause such intrapassenger mayhem aboard planes that she could scarcely imagine it. If you’re looking for an example of mission creep, there it is. The banning of nail clippers and pocket tools was never meant to protect us from each other -- it was meant to protect pilots and crews from attack and hijackings like those that took place on 9/11. As though the box cutters those terrorists used were the problem. The chief weapon of those terrorists was not box cutters but surprise, as we all learned by the end of that same day when passengers who understood what was happening prevented it. Those passengers learned the lesson, but the rest of us refused to, and we now accept airport infantilization as some sort of preventative -- like children holding our noses to take castor oil that does no good but our parents believe has magical powers. And every single person in the nation has forgotten that until September 10, 2001, people filed their nails and snipped threads on airliners without turning the rows at the back of the airplane into the state of Nature, red in tooth and claw. I’m thinking about this because I’m doing a lot of camping and a lot of flying now. When you camp your main job is to be prepared -- to have tools. Good tools allow you to cut food, prepare wood and wood chips to start a fire, use first-aid treatments, create a piece of cord the right length to solve a problem. Camping is an exercise in responsibility. The Boy Scout motto, after all, is "Be Prepared." (And I cite that with nostalgic fondness despite knowing with deep regret that one of their other current mottoes is, “Completely ignore scientific understanding of sexuality”). When you fly you have exactly the opposite job: your job is to be inactive -- to remain passive, to allow the airline to roughly stamp and impersonally handle you, like an unloved package sent book rate.* You cannot even avoid high airport prices by bringing your own soda pop to drink. Flying is an exercise in childishness, in inertness, the very opposite of what travel can be. Instead of broadening you air travel diminishes you, cures you of the instinct to manage yourself, take care of yourself. I’m doing all this flying and camping because of the Lawson Trek. Walking backroads and camping means tools and independence and problem-solving and fun for me just like it did for Lawson. The funding comes through MIT, which means I get to go to Cambridge and hang around with awesome people, but that also means plane travel and anomie and wanting to overthrow the United States government, which associates having a tool with being dangerous. You know all this by now; it’s not new and I’m just complaining. But the combination of increased need for tools plus extra interactions with the chief agency for idiotic untooling makes for the kind of frustrations I’ve described. Leave out that passengers and crews recognize that any disturbance aboard an airplane is life-threatening, so nobody gets away with anything on board anymore. And if somebody actually were trying to seize control of an aircraft you were aboard, which would you prefer to fight him off with: a plane full of passengers with pocket knives or a plane full of passengers with plastic forks and soda straws? During the uproar, couldn’t someone creep down along the aisle and stab him in the ankle? And leave out that I have accidentally boarded planes with knives at least a dozen times since 2001 and had to mail home tools I found myself with in far-off places, so even protecting us from our tools works only spottily at best. Just think about whether you like to have a tool or not. Lawson would not have considered leaving his home, whether for the civilized town of Charleston, with its two thousand cosmopolitan residents, or the wooded riverside camps of the Congaree or Wateree. He might have needed to cut a cord, bind a wound, cut through greenery, perhaps even defend himself. So he’d have brought along a knife. Same for you. Think about whether you’re better off with a way to address a glasses screw malfunction, a hangnail, a stuck briefcase zipper. Or any number of the food, equipment, vegetation, first aid, or personal problems a pocket knife helps you solve on the trail -- or on the street, or at someone’s party. I don’t mind the airport shoe dance and the belt dance and the laptop dance and all the other pointless games of let’s-pretend the TSA has us play. If it makes you people feel better, what do I care? But when you train an entire population to leave its tools at home -- to choose unpreparedness as a matter of preparation -- you’re doing wrong. A nation that supposedly prides itself on its individualism and get up and go, that’s prepared to fight to the death for guns (which statistics show you are way better off without), meekly decides to not fight back but instead to simply do without a tool that solves countless simple problems. (Meanwhile, go ahead, resist this motion towards meekness -- like the families that let their children roam free. See what your neighbors think of you.)

And if someone comes along to tell them they’re not allowed to have a little pocket knife?

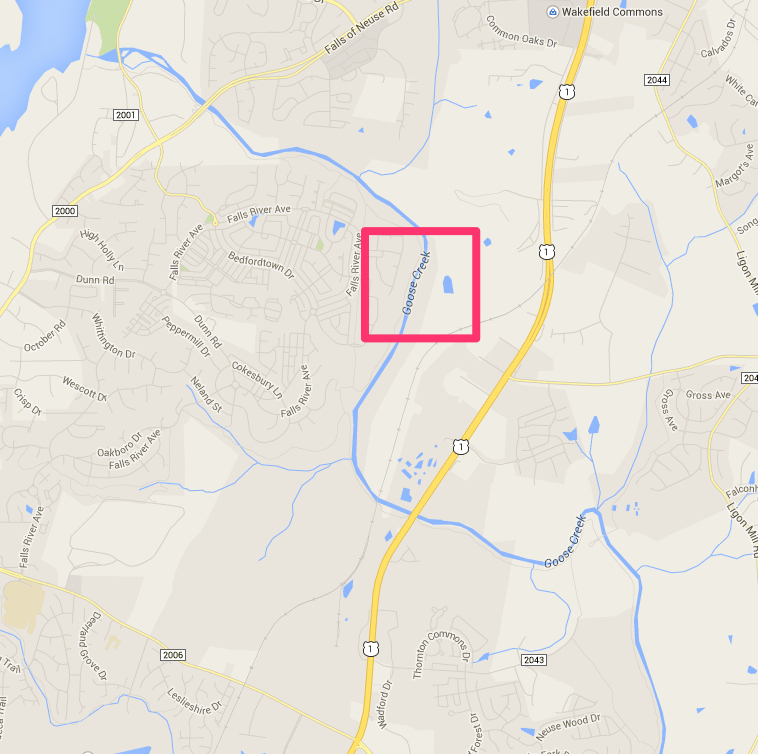

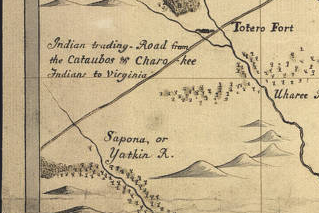

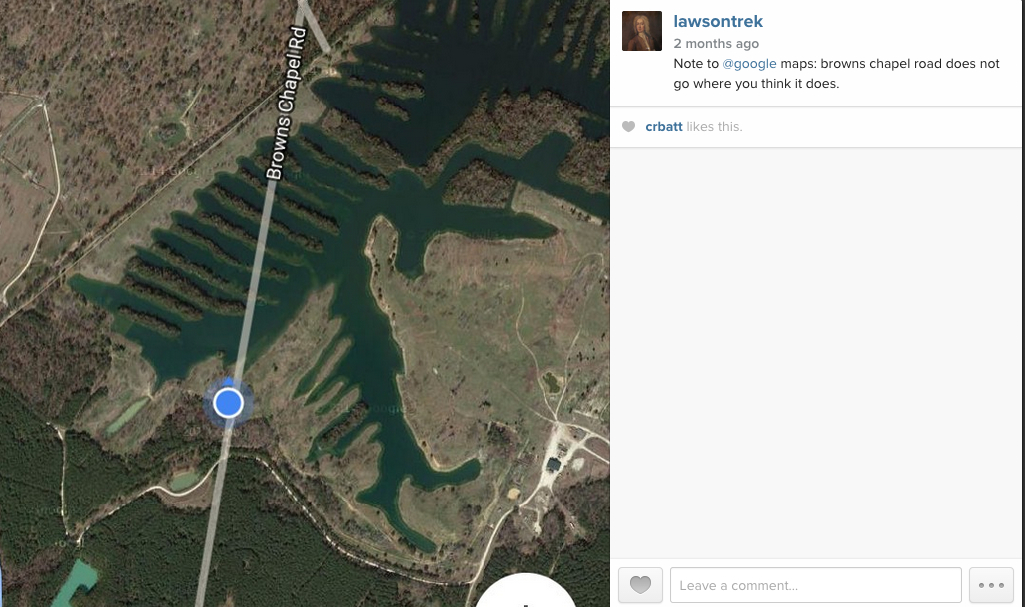

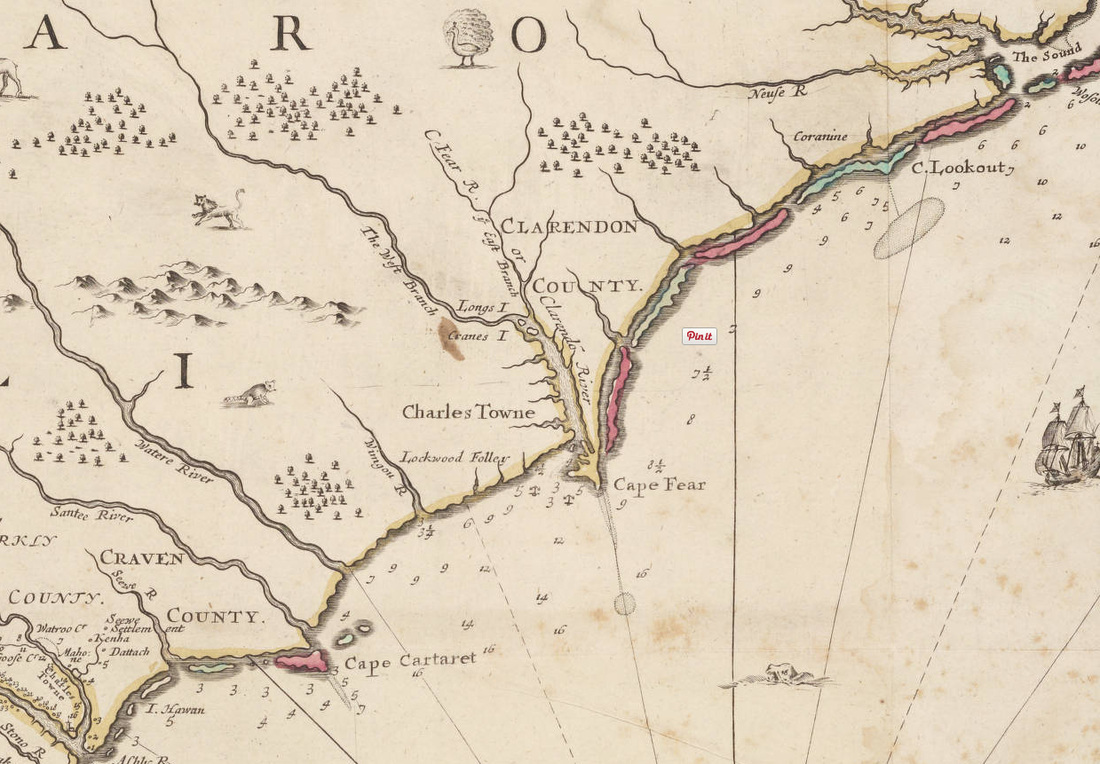

I hope they stab him in the ankle. ____________________________________________________ *I have used that metaphor once before. I don't think that's bad, and I think it fits here and is worth reusing. I just didn’t want you to think I was doing so accidentally. So I'm planning next steps, and in checking a map to plan my steps between Horatio, where I stopped last time, and, oh, say, somewhere up on Lake Wateree. Checking into routes, I stumble onto a map from 1733 by Edward Mosely, which includes a detail of an Indian trading path. It also has a kind of weird representation of the Neuse River, which runs through Raleigh, where I live, so to check on its trustworthiness I brought up Google Maps to do a side-by-side.  When I opened up Google Maps, I found that the Neuse River, which has run through this part of the world for thousands of years and perhaps much longer, has suddenly been renamed the Goose Creek, according to Google Maps. This is the type of thing that will get you going. So, thing one, I sent them a notice on their WTF page, which reassuringly promises to keep me updated on the progress of the correction. They even sent me an email. So far no change. Now, I'm sure this will be fixed before long, but what I'm trying to figure out is how it got changed to the wrong thing in the first place. This interview from Science Friday only Feb. 20 discusses the people behind Google's Project Ground Truth (here's a good explanation of the project by CNET), which plans, according to its website, "to map the world from authoritative data sources, via a unique mix of algorithms and elbow grease." Craig Miller, of Wired's Map Lab blog, tells SciFri that keeping Google Maps up to date is quite a project: "New roads are being built, housing developments pop up, shopping malls get torn down. So there's a lot of change to keep the maps accurate and up to date." Google uses artificial intelligence -- from all those satellite and street view images -- and all kinds of other data to share the vast amounts of information its maps provide. As you know, the maps still make mistakes -- this is far from the first error the Lawson Trek has encountered along the way. Miller says Google gets tens of thousands of error reports every day. So we can't be enormously surprised that even a day later the Neuse is still the Goose (Apple Maps, of all places, still has it right, by the way; so does Openstreetmap, the Google Maps predecessor that uses government data and crowd sources in a sort of wiki arrangement.) This mapping business is worth thinking about. I learned a bit about it from Dale Loberger (and expect to learn more soon), but as I walk, I am coming to recognize that my experience of my journey is profoundly affected by my maps. I can check my phone, my medium-scale DeLorme maps that I copy from DeLorme's indispensable gazetteers before each journey. On its website DeLorme characterizes those state atlas-gazetteers as "mapping America's back roads," which is exactly fair. You'd never want a DeLorme map book if you were looking for an address in a city or town, but looking for roads -- everything from vague farm roads to interstate highways -- that lead from one place to another? DeLorme is your source, and every Lawsonian I know carries a well-loved DeLorme around along with his or her copy of Lawson. Now Lawson himself created a map, though the only important information advances on it were names and placements of Indian tribes. And he'd have been familiar with earlier maps, though in 1700 maps of the Carolinas were pretty vague. I'm interested in how our maps affect our perceptions of reality: "the map is not the territory," as Alfred Korzybski famously said in 1931, expressing what is called the map-territory relation. The map is a representation of the territory, and it's always got room for error and improvement. Whether it's uncertain maps before or by Lawson or Google Maps suddenly going flooey after years of being right, or the globe in my office that shows the USSR -- or the amazing 30-foot Mapparium in Boston that has preserved in stained glass the world, inside out, as it was in 1935, a map is like anything else: it's made by people. It has perspective, the artifacts of the decisions made by its artificers, errors, breakthroughs.The traveler who gets where he's going without ever lifting his eyes from his atlas and the one who follows Siri to the wrong place are both missing the point. The map is a representation. The idea is to get to the place.

That's why we're out here. I'll keep you posted on what comes of Neuse River/Goose Creek. |

Archives

January 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed