And the thing is I can't lose notebooks; I just can't. Notebooks are work and notebooks are records and I'm a writer, so where I write is pretty much everything. I can't lose a notebook.

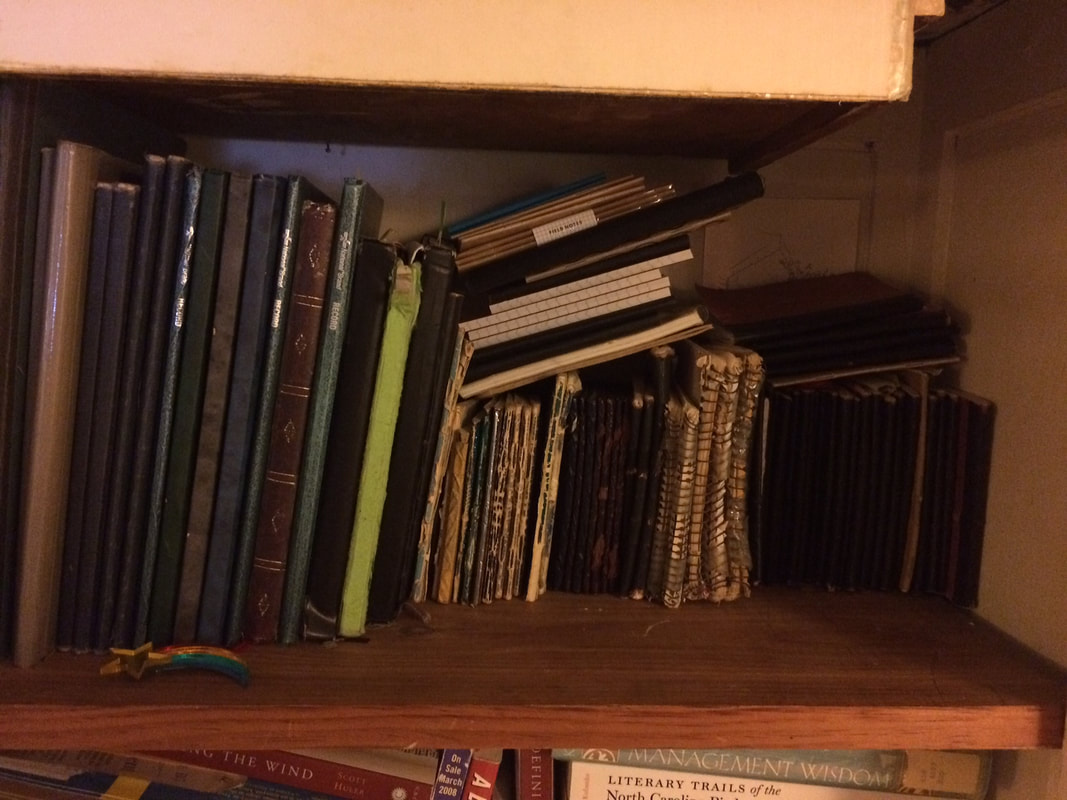

I started carrying a notebook around in my pocket, for stray thoughts, things to remember, ideas, overheard quotations, and the like when I was in college, where I kept up the practice sporadically. Once I had a real job I recognized the need for a go-to place to make sure I didn't lose notes and I began the practice, at age 22 or so, of never not having a notebook with me. In those pre-cell phone days I put the phone numbers I used most often in the back, so that I could quickly refer to them. When I finished a notebook -- usually six to nine months -- I would copy the phone numbers forward into the new one, along with my address and phone number and of course the promise of a juicy reward for the notebook's return. I would go back through the book as I moved on to the next one and see if there were ideas or projects I had lost track of. Once I had a pile of them, I could go backwards and, by checking back pages, see who my best friends were in a particular period; here Sally enters, here Ver drops off, we never seem to not have David.

When I got enough of them I of course numbered them so that I could keep them straight, though I numbered them only in the archive; in my pocket they were just my notebook. And this was all, mind you, in the early days, when I thought being a writer worked like this: you sat at a desk, holding a pen, stroking your chin and looking skyward. Then, aha! The idea! And then you wrote it down. That is, I hadn't learned about reporting, and I hadn't realized that those few descriptions of actual things -- a bus going by, kicking up grit; a clerk arguing with a man in a store; a woman adjusting her coat as she came out of a department store revolving door into a chilly Philadelphia December evening -- were actually the beginning of my work as a writer.

And I never, ever lost one. My friends would joke about "making the book" when someone said something funny and I wrote it down, or they would take note when a conversation sent me to a quiet corner to scribble. The point is, I had notebooks. They were important to me. And I never lost one. I thought of losing a notebook the way a carpenter would think of walking away from a hammer or a drill. Unthinkable.

And then one disappeared. I was wearing pants that had the kind of loose, shallow, crappy pockets that have become common, and at some point the notebook wasn't there. I scoured my room; I returned to places recently visited; I emptied briefcases. But nothing. I had lost a hat and sunglasses in the same period, so I wondered whether I was learning something about my changing capacity to manage myself. After a couple weeks I gave up and launched a new notebook, with a 3 x 5 card on the shelf at the end, noting that after the last finished notebook (number 68) a lacuna would appear in the record. Over the next weeks the sunglasses and hat returned from friends' houses or resurfaced from beneath kitchen table crap, but the one irreplaceable thing was gone. It turned out not to be the end of the world, of course, and I tried to shoulder up and not cry. But it shook me; I had done something I considered utterly unprofessional: I had lost notes.

Then the book came back. Scouring for a FitBit fragment, my wife found it deep under the bed, likely ejected there during a particularly disgusted episode of end-of-day pants flinging. I embraced it like a relative or beloved stuffed animal. Then I went through it -- it had been misplaced early in its tenure, and I would not have lost much beyond my sense of myself as a competent adult. A few notes, only a couple of them about Lawson or his trip or my attempts to make sense of that.

I'm glad it's back, if only so that I can now think of myself once again as someone who has never completely lost a notebook.

| More, though, it reminds me of the importance of original sources. As I finish the book version of A Delicious Country I'm trying to put Lawson into context, and that's hard work because of how little we know about him beyond what he put in his book. We have a very few letters from him to James Petiver, the botanical collector and apothecary in London; we have a couple letters in which he is mentioned (British gardener George London calls him "a very curious person" and noted his recent book, high praise from a powerful man of science, and Lawson's surveying work receives praise from William Byrd in his Histories of the Dividing Line betwixt Virginia and North Carolina: "Thus we found the Mouth of Nottoway to lye no more than half a Minute farther to the Northward then Mr. Lawon had forrmerly done....a very inconsiderable variance"). |

I would love to have those. To see his handwriting (like I did when I looked at his original specimens in the London Natural History Museum), to see his thoughts in the moment he observed a river, a new Indian tribe, a mountain. But no -- whether he lost them at some point on his travels after publication or whether they were destroyed during the Tuscarora War when Lawson was killed, his notebooks and all other records of his process are gone.

It's too bad. Lawson was one of the greatest first observers among the European settlers of North Carolina; I wish we had the first impressions of those first observations.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed