It's beginning to look a lot like the coastal plain. This image is actually the Piedmont still, but you can see how the land has flattened out.

It's beginning to look a lot like the coastal plain. This image is actually the Piedmont still, but you can see how the land has flattened out. I want to tell you all about Wilson, a small city struggling to reinvent itself in the wake of the loss of tobacco farming and other traditional rural vocations that made it a coastal plain capital. Wilson is working hard on its downtown, encouraging the arts, and looking forward.

I want to tell you about Clayton, a smaller city (Wilson has close to 50,000 people; Clayton is closing in on 20,000), which is trying to combine a downtown focus on small business with the advantages it has by being part of the metropolitan Raleigh tech hub. I want to tell you about how it's felt to walk away from even the last hills and into the coastal plain, where the clouds put on a show every day and the land spreads itself out before you like a beach blanket. I want to tell you about the fried bologna sandwich I had in Papa Jack's, in Buckhorn Crossroads and the barbecue I ate at Parker's in Wilson, about what seems to be Lawson's crossing of the Neuse River and what may or may not have been Wee Quo Whom, a waterfall whose location has always presented a significant problem for route tracers.

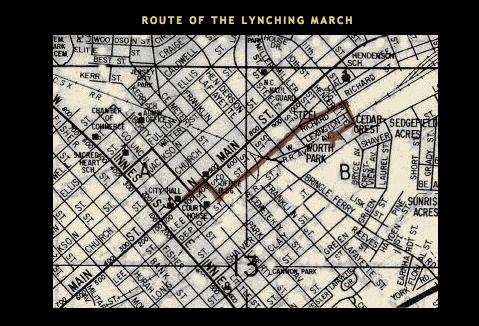

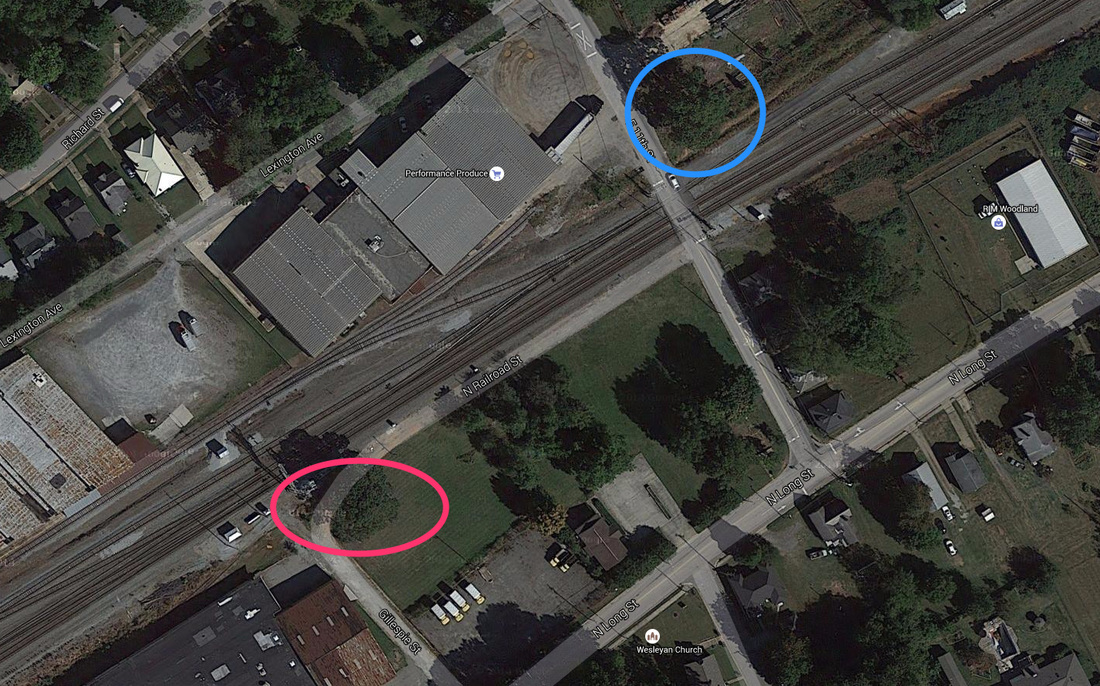

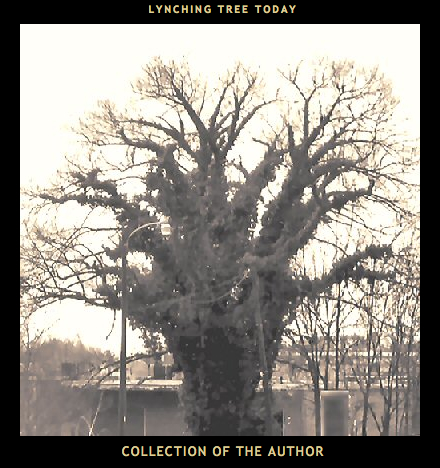

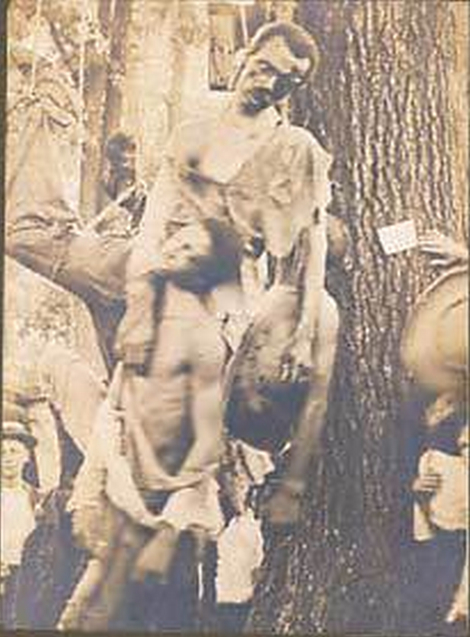

And yet instead I need to address an issue I thought we had resolved already. I'm talking, once again, about the possible hanging tree in Salisbury, which sparked a discussion -- a highly respectful discussion on all parts, I might add -- about the confederate flag and the history of racism in the Carolinas. (I updated things a bit here.)

Once again: by far the most delightful aspect of this discussion -- at least in these pages -- is the decency with which it's been carried on. I have spoken with people who vigorously support the flying of the confederate flag and people who think (as I do) that the flag represents a legacy of hatred and white supremacy. And we shook hands and we kept our voices modulated and we listened and smiled. We didn't change our minds much, but we engaged in civil discourse.

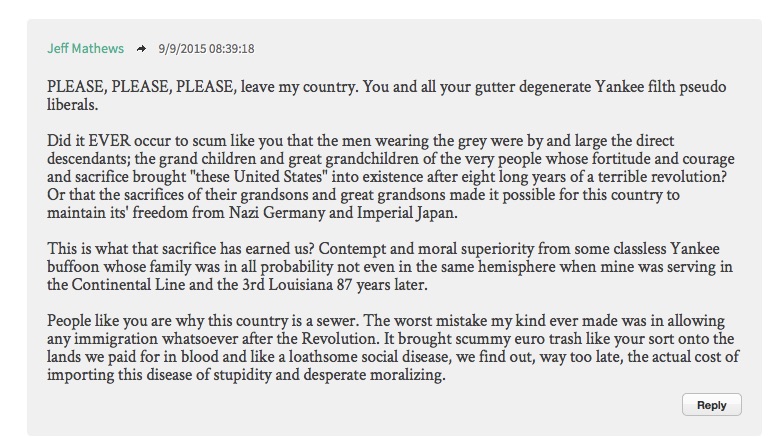

So then yesterday I got this comment on the blog.

This is John Jeffries. Lawson speaks with adoration of Eno Will, the finest of his Indian friends. I think I know how he felt. I'll tell you more about Mr. Jeffries in time.

This is John Jeffries. Lawson speaks with adoration of Eno Will, the finest of his Indian friends. I think I know how he felt. I'll tell you more about Mr. Jeffries in time. It's scarcely worth pointing out the tide of irrationality in his comments -- he seems to think that his ancestors stole the land of the United States from the Indians fair and square (and tried to seize it again through treason) so that means those of us who don't share that background are somehow, I don't know -- well, gutter degenerate filth, so the United States is his country and not ours. We see so much of this now and I find it heartbreaking. I will point out that the word "gutter" is commonly attributed to Louis Farrakhan about Judaism (whether he ever said it or not is another entire question. And meanwhile, the Nazis famously despised "degenerate" art, so once you're using code words like degenerate and gutter, you're aligning yourself with some pretty troubling things.

I need to tell you this: I have sat across from Peggy Scott of the Santee Indians, who was kind and decent and delightful, across from John Jeffries of the Occaneechi, who was kind and decent and delightful. (I haven't been able to tell you about him yet, but take a look at this until I can.) If anyone -- anyone -- could complain about people showing up and ruining a country -- well, you know. The point is, Mr. Mathews is spewing a kind of vicious, ignorant, cowardly hatred that pollutes everything it touches, and it hurt my spirit to leave it rotting in the comments thread of this blog, and it hurt even worse to delete it, as though I were afraid of it.

So I'm sharing it here. And in that spirit I also say, once more: the vast majority of people with whom the Lawson Trek has interacted -- in fact, simply everybody else -- has shown such kindness and generosity that this ugly attack so near to the end of the project serves only to underscore that. I am grateful for that more than I can express.

To cleanse the stain of Mr. Mathews' vileness from our spirits, I will do something I should have done much more of throughout this project but only just thought of literally this very second: I'm going to share a bunch of photos and captions to show what it's looked like from the Lawson Trek the least couple hikes. Thanks for reading. And as for Mr. Mathews and his ilk, I suggest we just do what his favorite song asks us to do anyhow: look away.

| |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed