But he did something profoundly important just before that -- in 1710: he gathered botanical specimens that he sent back to England, for one James Petiver, an apothecary "at the sign of the White Cross in Aldersgate Street, London." Collectors in those days were the equivalent of museum directors and scientific foundations now, sending agents all over the world to gather specimens or reaching out to travelers and asking them for any specimens they could provide. Lawson wrote to Petiver in 1701, after the completion of his journey, responding to an ad Petiver had run: "I design yr. advertismts. in order to for yr. collections of Animals Vegitables etc.," he tells Petiver. "I shall be very industrious in that Employ I hope to yr. satisfaction & my own, thinking it more than sufficient Reward to have the Conversation of so great a Vertuosi," vertuosi being what such collectors were called back then. In 1698 Petiver wrote to his apprentice, traveling through the West Indies, "Wherever you come enquire of the Physitians of Natives what herbs etc. they have of any Value or other use in Building, Dying etc. or what shrubs, Herbs etc. they have that yield any Gum, Balsam, or are taken notice of for their Smell, taste etc. and each of these get Samples with the names they call them by."

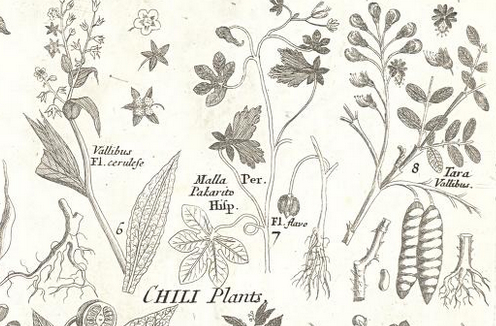

| Evidently Petiver never responded to Lawson's first letter, or in any case Lawson got busy with other things. The next piece of correspondence we have (on file in the British Library, no less) is from 1709, thanking Petiver for a book and pledging to stay in touch when he returned to Carolina. Lawson was then preparing to return from England, where he had gone to publish his book and be appointed Surveyor-General for North Carolina, which would require considerable travel, allowing him to gather the samples he promised Petiver. "Sr. I hope long since you have Received ye Collection of plants & Insects in 4 vials wch I sent for you," Lawson writes to Petiver in 1711, including "one book of plants very slovingly packt up." Lawson blames "ye distracted Circumstances our Country has laboured under" (the colony was suffering under the political and religious war called the Cary Rebellion), but you and I both know that's just a variety of the usual mealy mouthed deadline apologies we all send. Anyhow, Petiver got the stuff, and he included the specimens in his collection. An example of what eventually came of Petiver's collections can be found here, in the South Sea Herbal, one of many books (pamphlets, more like) made showing off the kind of stuff Petiver was collecting and sharing. So you can understand why our pal Lawson, interested in |

Hans Sloane, whose collection formed the foundation of the British Museum.

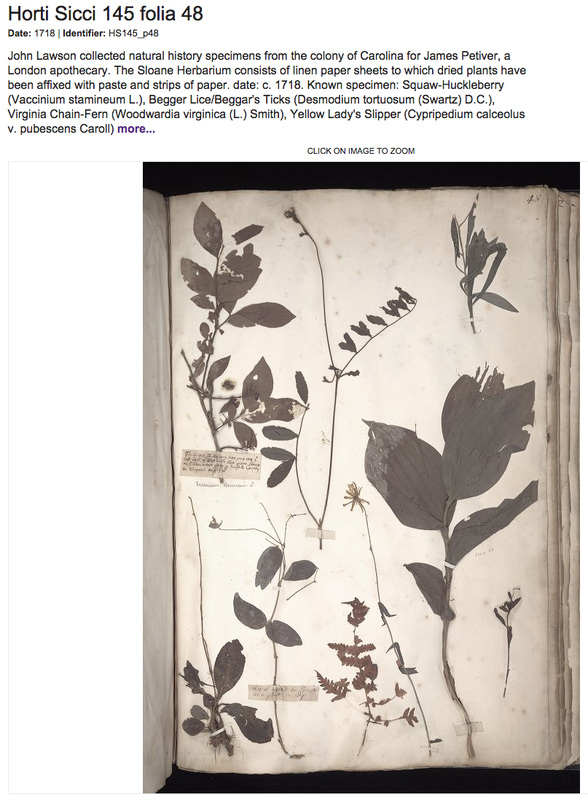

Hans Sloane, whose collection formed the foundation of the British Museum. But a bunch of specimens, yes. About 300 total, according to Vince Bellis of East Carolina University, who got images of the specimens from the Natural History Museum in London, where they reside. You can see them all online through ECU, here.

Wait -- the specimens reside? Somewhere? Still? Like, I could actually go see them?

Yep. So that's what's up right now. See, Petiver's collection was so good that ubercollector Hans Sloane tried to buy it, and after Petiver died, Sloane did. Then, when Sloane died, he left his collection to England, which used it to begin the British Museum. In 1992 the botanical (and some other) stuff peeled off to become the Natural History Museum, its own entity. And at the Natural History Museum they have an herbarium.

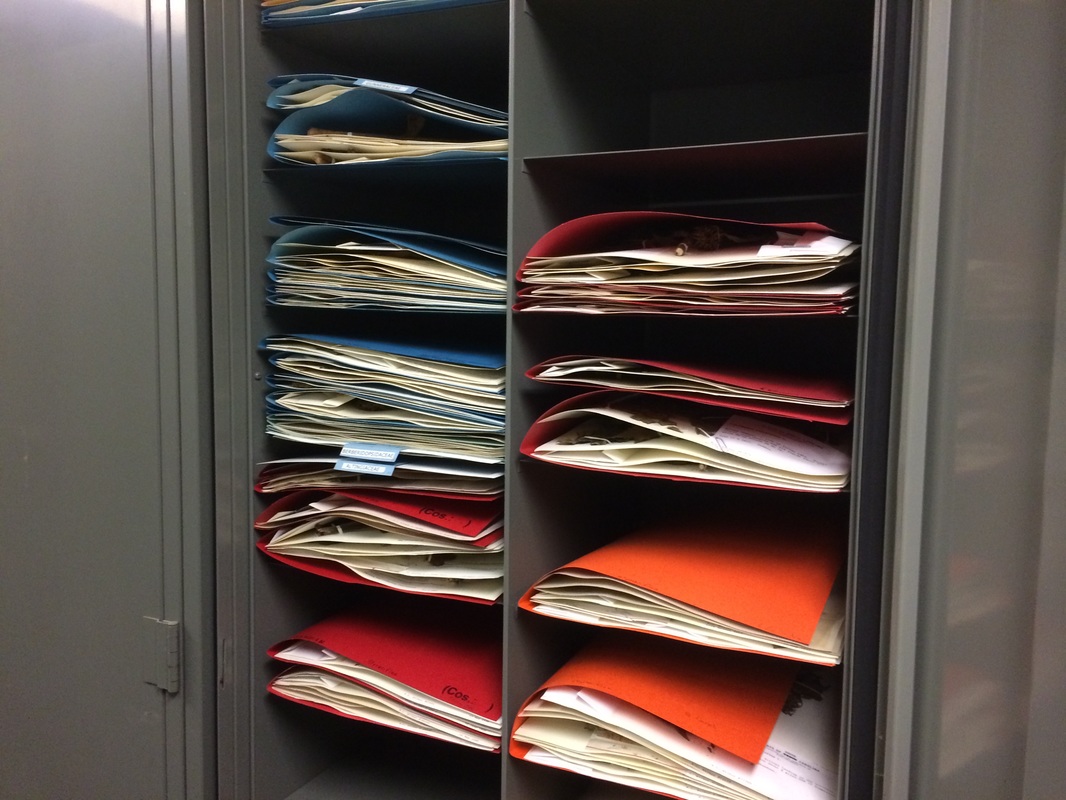

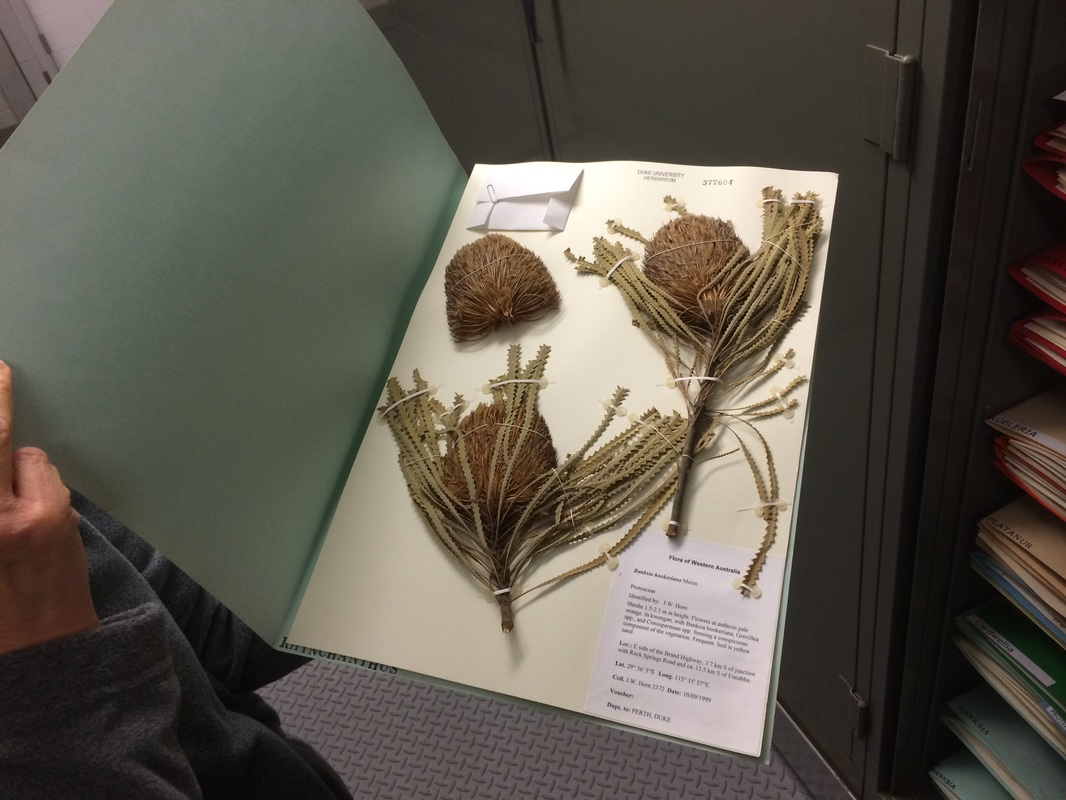

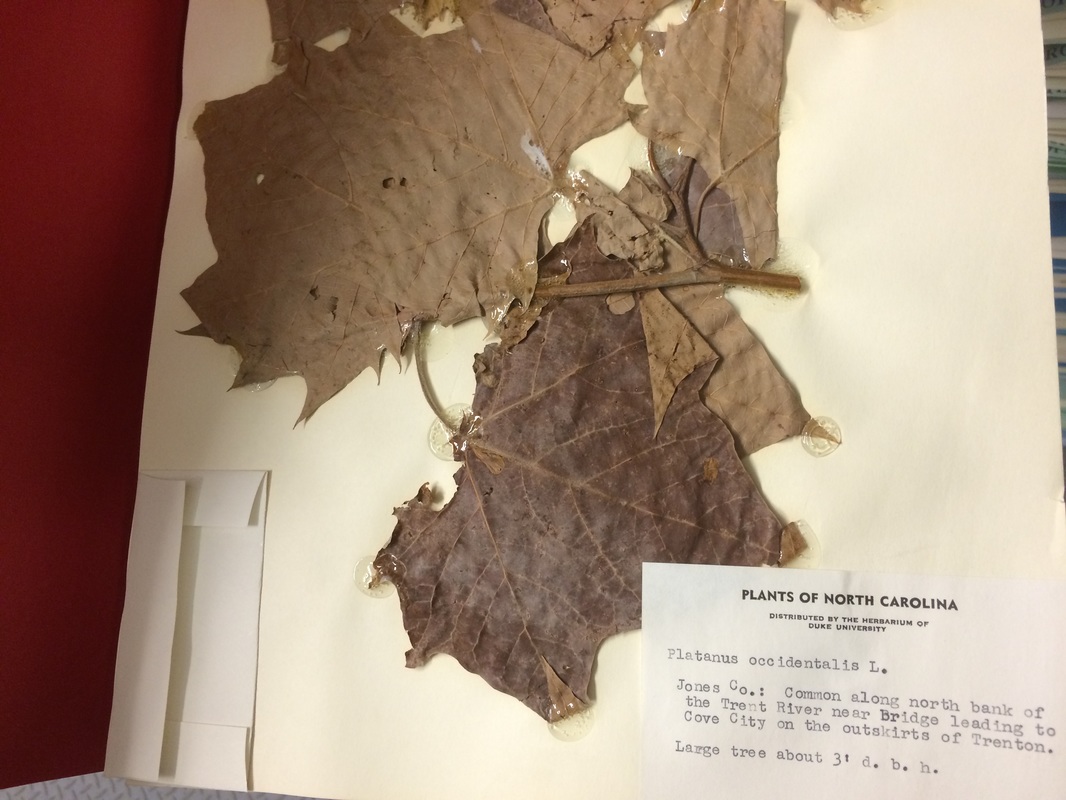

Those, I get. I have been to the herbarium at Duke University. An herbarium is pretty much just a bunch of drawers full of plants, but they're of course climate controlled and organized and filed. In fact, the whole Duke Herbarium is basically a set of those sliding file cabinets that you work by cranks. As far as "archive museum old books sexy" goes, you might as well go to your public library's microfiche collection.

The point: you can go into an herbarium and see all these cool original specimens gathered over the last half-millenium or so, and when you look at them you get that sense of being with a scientist as she or he gathers, prepares, dries, and presents a piece of the world for classification and understanding.

| You read about where the specimen was gathered, who gathered it, what they noticed. It's like you're with the scientist. So I am going to the Natural History Museum, where I'm meeting Charlie Jarvis, a friendly researcher in the museums historical collections who will bring out Lawson's specimens from Petiver's portion of Sloane's collection and let me see them. I'll get to see Lawson's handwriting and his style, and I can estimate to what degree his speciments were "slovingly" collected as well as packt up. They were mostly gathered near New Bern, according to Bellis. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed