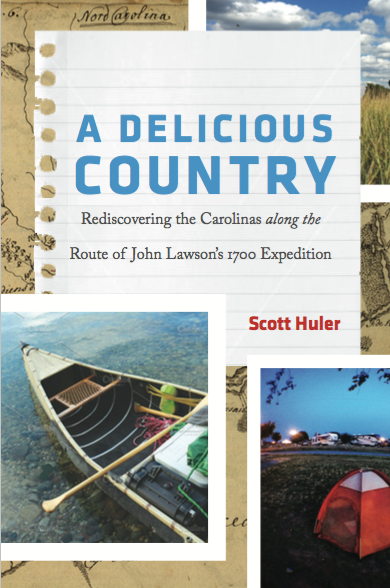

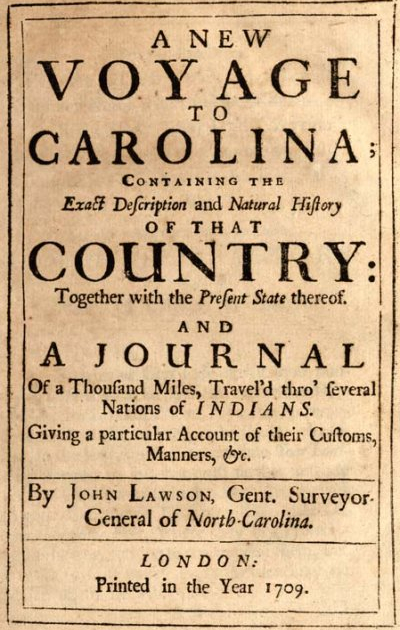

In March 2019 it will be in bookstores, but starting this very second you can order it online right here. If you want to see what the publisher, the University of North Carolina Press, has to say about it, click the link. If you want to see what they have to say about me, click here. It ain't much. If you're hungry for more information about me and my other work, try my home website, here. I'm very interesting.

Of more account, here are some initial responses to this book, by writers I deeply admire and whose praise means an enormous amount to me.

"An absorbing read. Huler's experiences during his modern trek do not, of course, duplicate what John Lawson found so long ago, but forms of beauty and dispossession rhyme down the centuries in thought-provoking patterns."

--Charles Frazier, author of Varina

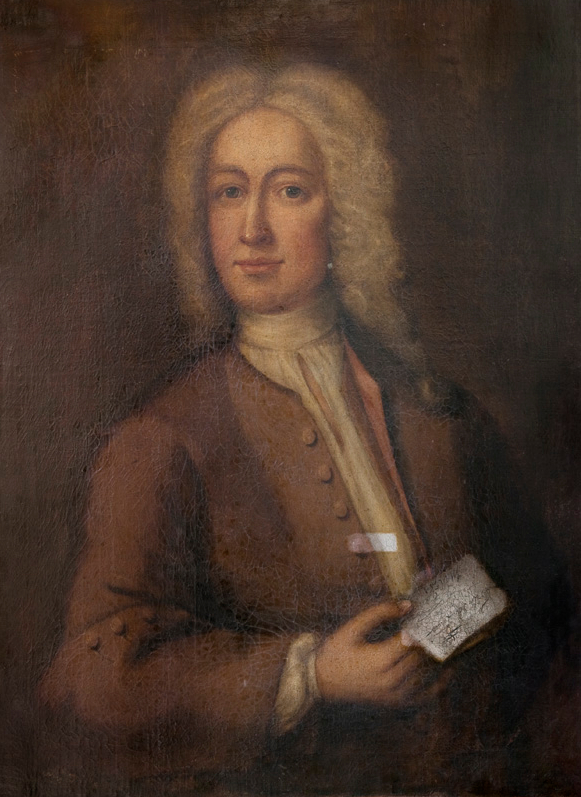

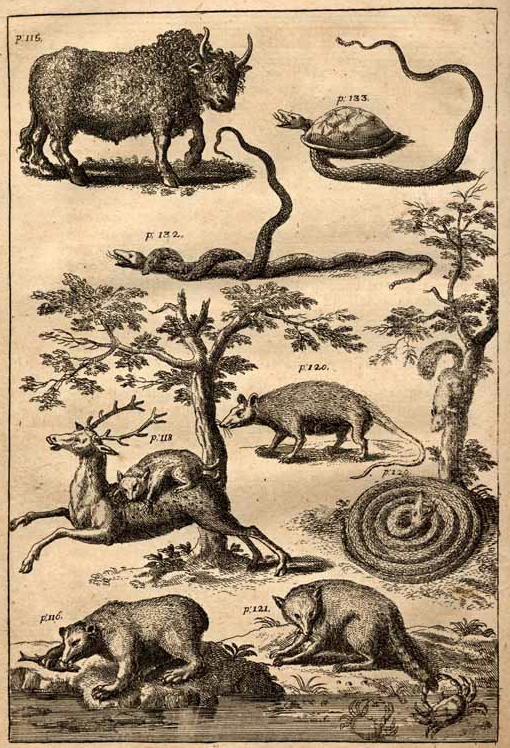

"It's been said that one of the only true plots is this: A man goes on a journey. In A Delicious Country, Scott Huler demonstrates why that narrative arc retains such strength. His retracing of John Lawson's epic circumnavigation is thoughtful, relaxed, humorous, and generous. It retrieves for us a lost world of discovery and wonder and reminds us that the goal of every departure is to learn to value home."

--Maryn McKenna, author of Big Chicken: The Incredible Story of How Antibiotics Created Modern Agriculture and Changed the Way the World Eats

"An eye-opening journey through the contemporary South. As he does in his other excellent books, Huler reminds us in A Delicious Country that the present and the past coexist all around us. He writes with great specificity about each topic at hand, but he never loses sight of the larger human story. The book excels as a work of exploration, history, and science. It is also simply what reviewers like to call 'a rousing good read.'"

--Michal Sims, author of The Adventures of Henry Thoreau

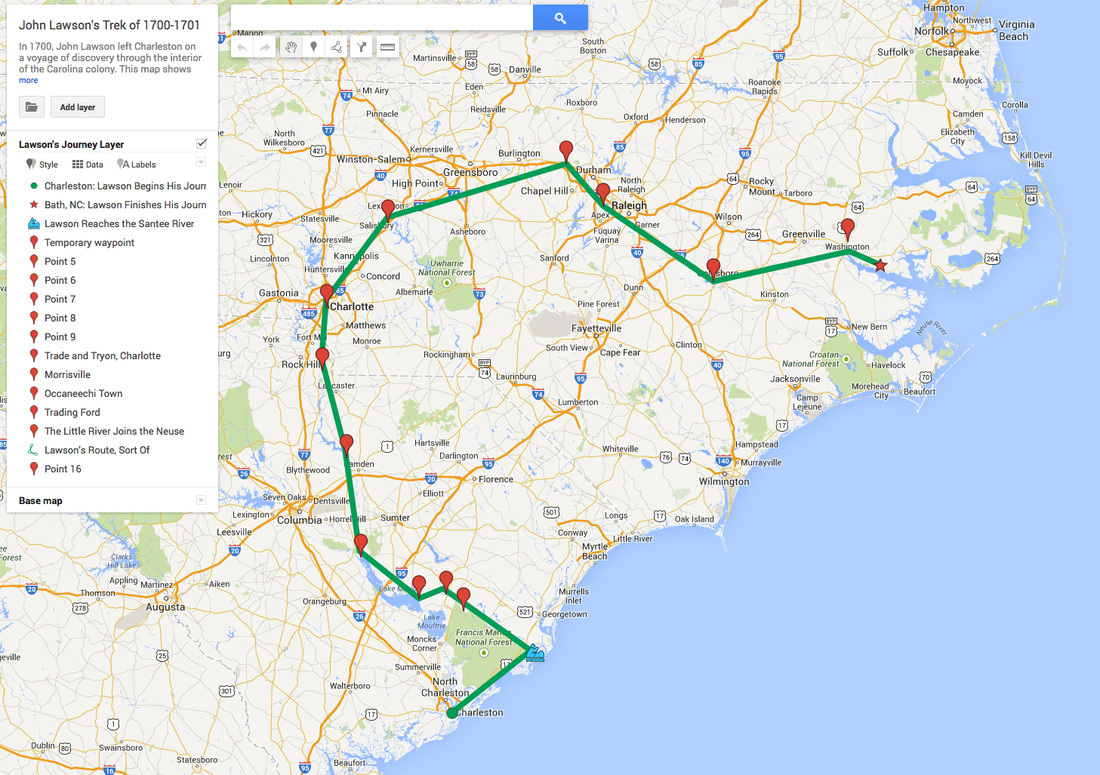

"From the boggy salt marshes near Charleston to the parking lot of the Charlotte Motor Speedway and beyond, Scott Huler has breathed new life into the English explorer John Lawson's all-but-forgotten 1700 journey through the Carolinas. While much of the physical landscape has changed over the centuries, the characters who inhabit it are still vibrant, still contradictory, still completely unforgettable. Only a storyteller as warm and witty as Huler could wrangle such a sprawling, complex natural history into an engrossing travelogue that leaves the reader wanting nothing but more."

--Bronwen Dickey, author of Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon

Next come all the inevitable moments of weirdness that come with publishing a book One day a truck comes to our house, and then there's a box of books. And you open the box and there it is, and there's your work, and there's your name, and it all seems a little embarrassing, and you want to apologize that you've put everyone to so much bother. I worked in a bookstore when I was just out of college, and we were all writers of course, and we used to open the boxes of books, glossy book covers of Michener and Stephen King, and smooth shiny paperbacks, and we would clutch them, rub them against our cheeks: "One day," we would murmur, "one day, this will be me. ..." And then one day is here again, yet once again without the trumpet voluntary and footmen in livery that seemed so likely back when it was only imaginary.

Then will come bookstore events with unpredictable attendance, and media appearances where I sound like a knucklehead and how could they have gotten so much wrong, and reviews of some other book the reviewer must have mistakenly conflated with mine, and then the occasional panel discussion and festival where the author next to me will have a line of well-wishers out the door and my handler will say of my few greeters, "Oh, this always happens! But you were up against [almost anyone else], so please don't feel bad" and then will disappear out of awkward embarrassment into her or his mobile phone.

I have been here before. But I must also say: of these many years of work I will now have a record, and those authors above, august company indeed, consider it worthy of comment, and so for the moment, at least I will say only, like that creepy tall guy said in "Twin Peaks," It is happening again. Let's all hope for the best, shall we?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed