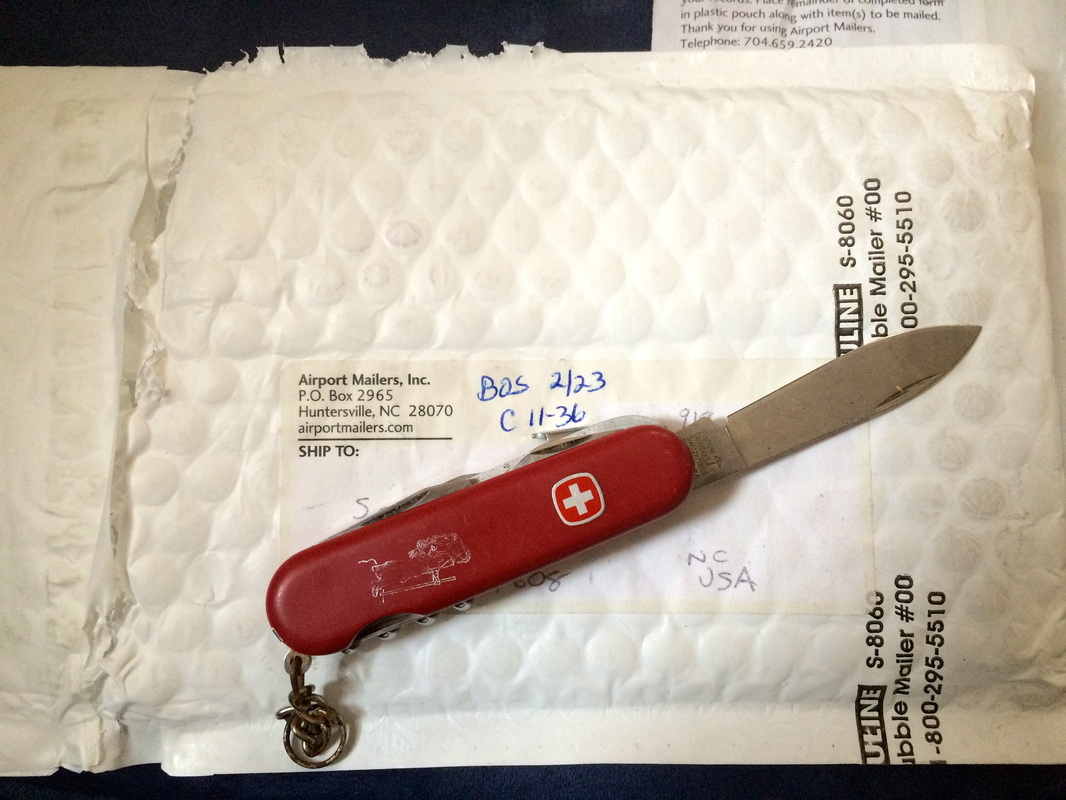

Because I was sawing through the pepperoni with my crappy backup knife because my regular knife was en route to me somewhere, probably. I had mailed it back to myself -- perhaps the tenth time I have performed a variation on this idiotic gavotte -- from Logan Airport in Boston, where I was stunned to find it in my shoulder bag. It had slipped through the screeners on the outbound from Raleigh-Durham, where I live, so I found myself having to cope with it at an away airport, where I haven’t chosen a spot to secrete it if it accidentally makes its way to the airport with me.

You might still believe this all has something to do with protecting ourselves from terrorists, but if you think that you’re a fool. In 2013 the TSA floated the idea of allowing people to carry their tiny little personal tools with them on airplanes but the flight attendants -- among others -- want mad. I wasn’t surprised -- a flight attendant I know, when I loudly scoffed at TSA protecting us from our tools, told me she thought allowing passengers to have sharpened implements would cause such intrapassenger mayhem aboard planes that she could scarcely imagine it.

If you’re looking for an example of mission creep, there it is. The banning of nail clippers and pocket tools was never meant to protect us from each other -- it was meant to protect pilots and crews from attack and hijackings like those that took place on 9/11. As though the box cutters those terrorists used were the problem. The chief weapon of those terrorists was not box cutters but surprise, as we all learned by the end of that same day when passengers who understood what was happening prevented it. Those passengers learned the lesson, but the rest of us refused to, and we now accept airport infantilization as some sort of preventative -- like children holding our noses to take castor oil that does no good but our parents believe has magical powers. And every single person in the nation has forgotten that until September 10, 2001, people filed their nails and snipped threads on airliners without turning the rows at the back of the airplane into the state of Nature, red in tooth and claw.

When you fly you have exactly the opposite job: your job is to be inactive -- to remain passive, to allow the airline to roughly stamp and impersonally handle you, like an unloved package sent book rate.* You cannot even avoid high airport prices by bringing your own soda pop to drink. Flying is an exercise in childishness, in inertness, the very opposite of what travel can be. Instead of broadening you air travel diminishes you, cures you of the instinct to manage yourself, take care of yourself.

I’m doing all this flying and camping because of the Lawson Trek. Walking backroads and camping means tools and independence and problem-solving and fun for me just like it did for Lawson. The funding comes through MIT, which means I get to go to Cambridge and hang around with awesome people, but that also means plane travel and anomie and wanting to overthrow the United States government, which associates having a tool with being dangerous.

You know all this by now; it’s not new and I’m just complaining. But the combination of increased need for tools plus extra interactions with the chief agency for idiotic untooling makes for the kind of frustrations I’ve described. Leave out that passengers and crews recognize that any disturbance aboard an airplane is life-threatening, so nobody gets away with anything on board anymore. And if somebody actually were trying to seize control of an aircraft you were aboard, which would you prefer to fight him off with: a plane full of passengers with pocket knives or a plane full of passengers with plastic forks and soda straws? During the uproar, couldn’t someone creep down along the aisle and stab him in the ankle? And leave out that I have accidentally boarded planes with knives at least a dozen times since 2001 and had to mail home tools I found myself with in far-off places, so even protecting us from our tools works only spottily at best.

Just think about whether you like to have a tool or not. Lawson would not have considered leaving his home, whether for the civilized town of Charleston, with its two thousand cosmopolitan residents, or the wooded riverside camps of the Congaree or Wateree. He might have needed to cut a cord, bind a wound, cut through greenery, perhaps even defend himself. So he’d have brought along a knife. Same for you. Think about whether you’re better off with a way to address a glasses screw malfunction, a hangnail, a stuck briefcase zipper. Or any number of the food, equipment, vegetation, first aid, or personal problems a pocket knife helps you solve on the trail -- or on the street, or at someone’s party. I don’t mind the airport shoe dance and the belt dance and the laptop dance and all the other pointless games of let’s-pretend the TSA has us play. If it makes you people feel better, what do I care?

But when you train an entire population to leave its tools at home -- to choose unpreparedness as a matter of preparation -- you’re doing wrong. A nation that supposedly prides itself on its individualism and get up and go, that’s prepared to fight to the death for guns (which statistics show you are way better off without), meekly decides to not fight back but instead to simply do without a tool that solves countless simple problems. (Meanwhile, go ahead, resist this motion towards meekness -- like the families that let their children roam free. See what your neighbors think of you.)

| Again: I come off like I’m just complaining, and maybe I am. Then again, maybe not. My trek in recent weeks took me to Poinsett State Park in South Carolina, where instead of mere souvenirs the counter in the wooden office building offered firestarters, shirts, water bottles. Among my options should I choose to bring something home for my boys, 6 and 10, were tiny little pocket knives. You know the ones: knife blade, nail file, scissors, plus a little toothpick and tweezers exactly the right size for a kid to lose in fifteen minutes. They were three dollars. I had driven to South Carolina, so I had no TSA to contend with. I bought one for each of them. The boys were thrilled. One of them idly whittles now when he remembers he’s got the knife. They both know all kinds of rules -- no pointing, no stabbing, no walking or running with an open knife, whittle only away from your body -- that will make them safer, more resilient, and more prepared kids. They were told to store the knives in their desk drawers, and that’s where the knives reliably now reside. The kids are learning one of life’s great lessons: a good tool helps you. Learn your tools and to use them responsibly and you won’t regret it. |

I hope they stab him in the ankle.

____________________________________________________

*I have used that metaphor once before. I don't think that's bad, and I think it fits here and is worth reusing. I just didn’t want you to think I was doing so accidentally.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed