If you're wondering, this is the house I was taking a picture of. No picture of my new friend -- he preferred not to.

If you're wondering, this is the house I was taking a picture of. No picture of my new friend -- he preferred not to. And, as sometimes happens, someone comes over. I'm snooping or I have out a notebook or I'm pointing a camera, so somebody strides or drives over -- in this case drove, pulling smoothly but quickly into the drive directly in front of me. I don't remember what he said first -- tall slim white guy, probably late 60s, if I recall correctly smoking. Driving -- I can't believe how little I observed! -- some kind of long two-door, I THINK, probably domestic. I must have been asleep. Or at the very least paying attention to the house I was shooting.

Anyhow. "You okay?" he asks me, very polite and it's worth noting without a hint of threat or defensiveness. But it was his neighborhood -- he'd been shooting the crap with the guy across the street, at the car lot/produce market/cattle farm. I'd seen them talking as I walked past and felt like they'd noticed me. I usually would cross the street to speak with people like that, but they were deep in an asphalt parking lot by a big aluminum barn, and I just couldn't bear to walk a quarter mile with them wondering who the hell I was the whole time.

So I explained who I was and gave him my elevator pitch about Lawson and his book and my project and so forth and then we were friends. He said he had been an investigative reporter at the Independent Tribune, so we enjoyed talking about work. He told me most of the people on these roads -- in these communities -- are retired now, and the farms that are run are either keep-busy farms or rented out, with only few of the latter. We talked about the stories we have to tell, and then history came up, and then he mentioned that of course nowadays we're rewriting history, and then of course here we went on the Confederate flag.

I don't have to share the specifics. Some facts, as far as I can tell wrong (the owner of the most slaves was himself African American?); some commonly heard themes about historical revisionism and states' rights. Even a claim, new to me, that the war was fought over taxes. (I have to admit: if people have really begun to convince each other that the Civil War was fought over taxes, it may be game over. I thought of Marlon Brando in "Apocalypse Now" saying, "My god, the genius of that.") But anyway, a simple interaction. I stopped along the road, a fellow told me how the locals lived, shared what they thought. It was a perfect interaction for a reporter like me, on Lawson's trail to see what's out there.

We parted cheerfully, wished each other well without reservation. And for about 30 seconds I congratulated myself on simply reporting, letting the story come to me, instead of challenging. And then I thought, you know, with the murders and the flag and the cops and all this, though it's fine to listen to everybody I come across, I had better take care to hear other voices than the ones from the people whose houses were on the main streets I was walking down. I had better make sure I hear everybody's voices.

I mean not that this was new. Lawson mentioned the Huguenots by the river, and Huguenot descendants I found. Lawson talked extensively about Indians (everyone I've met in the Santee and Catawba tribes referred to themselves as Indians, and so I do as well), and I've made an effort to make sure I have talked to and about them as well. I was stunned when I learned that for its first half-century, the slave port of Charleston made more money sending Indians to Barbados than it did bringing African and island peoples to the mainland, so this is good for me. I'm doing like Lawson did -- trying to get how things are here, how they've been.

So I decided that since the murders of African Americans, in churches or at the hands of police or private citizens, are so much in our discussions, I'd better make a special effort I got some African American voices in my chorus, and along I went.

The very next day I had a great opportunity.

I walked my first day from the little not-even-crossroads of Mt. Gilead, just north of Concord, into Salisbury. There I was well entertained, as Lawson was by the Sapona Indians. The next day I started in Salisbury and walked through town to the northeast, walking down Long Street, quickly leaving the prosperous downtown and entering the town of East Spencer, which I will describe with these images and this, directly from my notebook: "Long st a parade of the burned, the collapsed, and abandoned." I have a half-dozen similar images of burned-out buildings and houses.

Curtis on the left, Mike on the right.

Curtis on the left, Mike on the right. Anyhow, I introduced myself, shared business cards and pins and my little Lawson story -- and the story of the conversation of the day before. And off we went, cheerfully. In a town with the problems of East Spencer, Mike and Curtis did not think the Confederate flag was a big issue -- they were a lot more worried about employment, violence, and poverty and its attendant miseries. "As long as you keep a bunch of winos and run-down property in town," Tony said, you're not going to improve. They discussed water bills and troubled youth, irresponsible code enforcement and the failure to invest in the community. We never quite got to institutionalized racism and that sort of thing, but they said the makeup of the town was simple. Over in Spencer and Salisbury is where the white people and slave-owners had lived, and East Spencer was where the black people went -- literally on the other side of the tracks; enormous freights trundled through as we spoke. And they said it was within living memory that you were back across the tracks by nightfall if you knew what was good for you. As far as the flag went, Mike did say he actually approved of it: "I'd rather someone hung up the flag, then I know not to go there; I'll go somewhere else. Go there and I might get hung."

Mike had to leave -- he had started a nail salon, whose card he gave me -- but he expanded on that whole getting hung thing. He and Curtis had mentioned a boundary between East Spencer and Salisbury they called "the unemployment tree," and I was looking for a clarification on that, but I never got there because he brought up another tree. "Don't forget to see the hanging tree," he said, before he left.

The what, now?

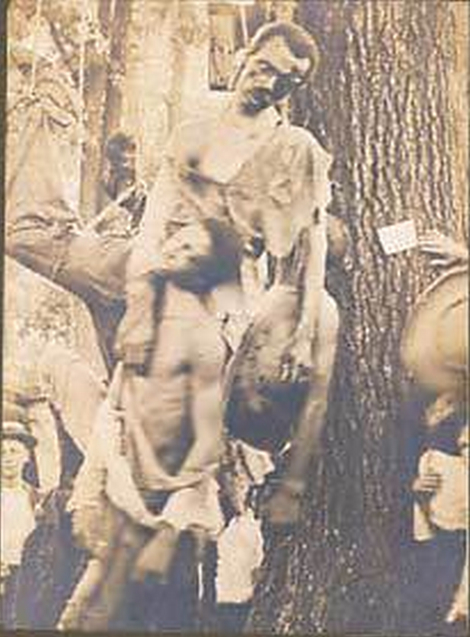

Yep: the hanging tree. I was to Google "lynching" and "Salisbury," and I would find an image of five men hanging from a tree, and the tree still stood on Seventeenth Street where it crossed the railroad tracks. Well, it's not five but three men hanging from a tree -- in 1906 -- and Seventeenth doesn't cross the tracks. Eleventh Street does, though. And according to this account (and map!) of the events, Eleventh Street was where I wanted to be. So I went there.

I spoke with Curtis for a while after Mike left, and then I went to see the tree. Around Eleventh Street there are warehouses and traintracks and such, but standing by itself was this tree, plainly old enough to have been large in 1906, and I watched it for a few minutes. No wreath, no flowers, no nothing -- just a tree, surrounded by a fence. It's not a symbol for Salisbury -- but it's a symbol for its black residents.

Anyhow off I went, along the path Lawson and I share.

Naturally, that turned out to be the day I saw a million Confederate flags, too. I took pictures.

I most certainly did not. I got a curt nod from the guy out front and I didn't even take a picture. Except then I walked into Denton and thought, "I want to talk to the guy flying those flags." So I drove back, pulled over across the street, and shot a couple snaps. As I sat there the same guy walked out and asked: "You okay?" With overtones only of helpfulness. "I'm fine," I said, and asked if it was okay if I took some pictures. It was, and he urged me to park in his lot. "When I saw you stop, I worried you had broken down," he said. He was genuinely checking to see if I needed help.

So I told him my story. And we talked. "The reason is, to me that flag does not represent color," Kary, the shop owner told me. His some-number-of-greats-grandfather fought in the war, which was fought because "the North was trying to take what the South had, tell us we couldn't do what we wanted." Like, I pointed out, own slaves, a point he yielded. But "to me, that flag represents me rebelling versus the government telling me what to do." He pointed to the American flag and said, "that's another thing about that flag -- you have the right to have an opinion."

This is Kary. He owns the shop, though not the building. We had an awesome conversation.

This is Kary. He owns the shop, though not the building. We had an awesome conversation. In fact, when I tried to explain that whatever his personal beliefs, there was no doubt that millions of people took the flag as a symbol that he was a racist, he said he hated that. So I made a gesture, raising my middle finger, though pointing it at the wall, not at him. "What if I put that on a flag and waved it in your face?" I asked. He admitted that might offend him, and when I said, "What if I told you that though that middle finger is universally understood to mean disrespect and meanness, when I use it I just mean you should remember to have a digital exam to make sure you don't have prostate cancer? Because I'm worried about you?" He smiled and even laughed, nodding. He got the point.

He didn't take down his flag, mind you, but he got the point.

Anyhow. That was last week, and I look at the conversations of that day is among the most important I've had on the trek. Like Lawson I'm out trying to see what's out there, who's out there, what's going on, and at the moment, we are talking about this flag, and I'm walking through its home territory. Lawson walked through North and South Carolina. And it was South Carolina still flying the Confederate flag on its state capitol grounds until the Charleston church murders convinced their legislature to take it down. And it was North Carolina KKK members, don't forget, who came down to make sure nobody thought all Carolinians were civilizing.

I was so glad for these conversations. Because I want it to be easy -- I want the house with the dirty yard and the flag to be symbolic of a Bad Person with Racist Views, and I want anybody who still flies that flag to be Bad and Wrong and Mean. I want it to be easy. But there were Mike and Curtis telling me that they were a lot more concerned about jobs and education and civic investment than in some flag, and they pointed me at the hanging tree. And there was Kary -- and so many like him whom I've met so often -- who genuinely believes that the flag is not a symbol of racism, and who genuinely believes, despite all the enormous, vast evidence that ths Southern states seceded to protect slavery and white supremacy, that the Civil War was fought over something other than slavery. (Here's the flag's designer, in his own words. Shudder.)

In fact, as a small aside, let me remind you that unlike Lawson, I am not having on my trek my first experience in this territory. I have lived here more than two decades, and I can remind you: people in the South? If nothing else, they are stubborn. Stubborn. With all the positive and negative things that word can carry. If you're wondering why people refuse to accept the unequivocal evidence that the war was about slavery and the flag was adopted as a symbol of white resistance to Civil Rights, try to remember that you may be dealing less with racism than with a streak of pure, gut stubbornness. That stubbornness is not unadmirable. Though I will say -- in this case it's horribly misguided.

We talk about the flag and the flag and the flag and the churches and blah blah blah but the reality is now, this very day, black people are being murdered in the streets. By criminals, by citizens, by amateur crimestoppers, by the police, over and over and over. There cannot be any doubt that this is a direct result of slavery and the war. And yet another black citizen is killed and we say, "Gracious me that's just terrible," and then we get into a long pointy-headed discussion about the damned flag.

Mind you: the flag should come down. Anybody who flies it? At the very least -- at the very least -- is saying, "I know that tens of millions of people will find this offensive, but I still think the fact that I can claim to my own satisfaction that I personally don't mean it that way outweighs the absolute certainty that those tens of millions of people will perceive this flag as racist and mean and vicious." This is at best selfish and at worst ... something much worse. We should take down the flag, and everybody flying one should know: people who look at you see Dylann Roof, not your great-whatever-great-grandfather, whether he personally owned slaves or not. By flying it you're choosing to side with the Dylann Roofs of this world.

One more aside -- monuments. The monuments should stand, every single one of them. Salisbury itself has had some discussion over its downtown Confedereate monument, which some would like to have removed. I completely oppose such Stalinist whitewashing. Salisbury's monument to Confederate soldiers is actually quite lovely, but it's also physical fact. And though I agree with all who find offensive and even absurd its inscription that it commemorates men who died for "constitutional liberty and state sovereignty," I would never take it down. Instead I'd add a new plaque giving more responsible information. [Update, 2020: Not sure I still agree with this sentiment; please see a piece I wrote for Duke Magazine about building and monument renaming and removal.]

More important, I'd build an enormous monument around the Hanging Tree -- a monument to every African American person lynched, to every African American person terrorized during Jim Crow, to every African American person ruined by centuries of state-sponsored racism. In the first place, why would you not? In the second place, what visitor to the Southeast would miss the Salisbury Lynching Monument, if it existed?

So that's it on flags, trees, symbols, and suggestions from the Lawson Trek. No answers, and certainly no easy shorthand. Flying the flag doesn't make you one of the racists -- but it certainly means that's who you're choosing to align yourself with. Anyhow that's what people are talking about right now, here in the Carolinas, where Lawson walked and where I walk along in his path.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed