I went on at some length about the confederate flag and such, and I learned a good deal from a good many people, including that Salisbury still had a standing tree from which three men were lynched in 1906.

Not so fast!

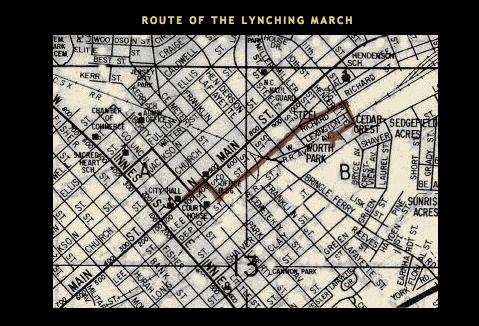

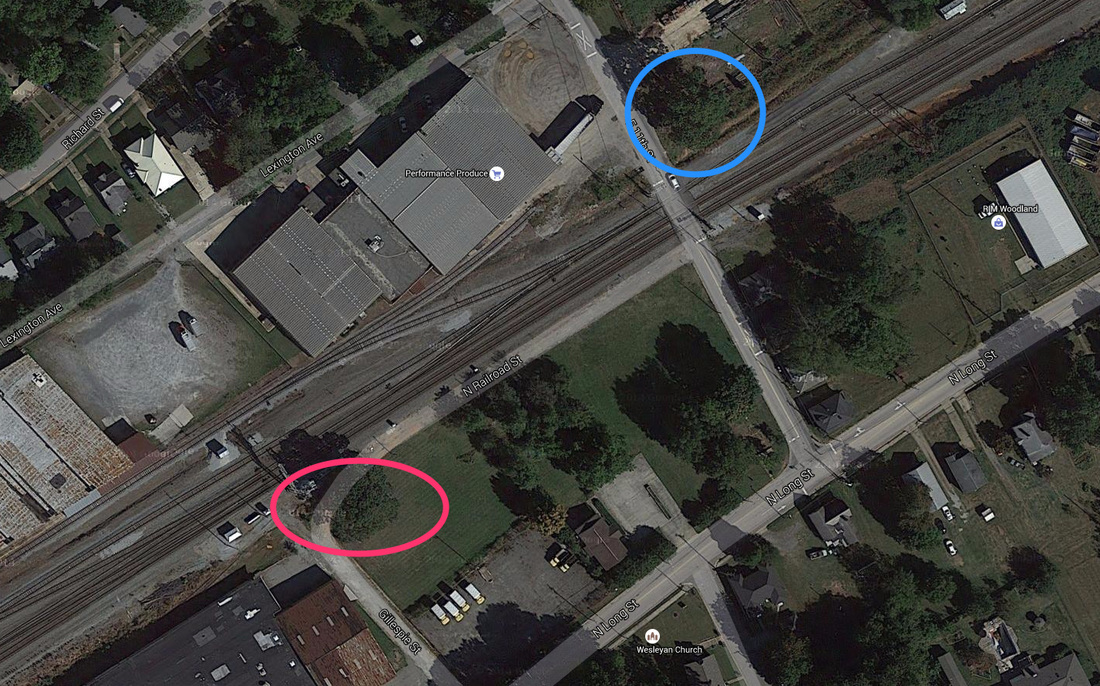

I've since heard from my friend and guide Susan Sides, who was very helpful to me while I was there, that the tree no longer stands. She suggested I contact Susan Barringer Wells, whose book A Game Called Salisbury details the lynching and the murder that led to it. Sides's email said that Wells's book claimed the tree still stands, and after publication (in 2010) she heard from many people that that was not the case. So I reached out to Wells to check. Wells told me that though she did hear from people who said the tree had come down, she's just not sure. There was another lynching in 1902, and some think the same tree was used both times; others are not so sure.

In any case, it's important that I back off from my claim. It's likely the tree I identified is not the lynching tree, and it's also likely that tree no longer stands. As Susan Sides said in her email, "I just want you to know our town does not have a hanging tree." Though I'm not at all sure there's certainty here (and I did acknowledge even in the original piece that I was far from certain about the tree), it's very certain that I don't have it.

Now, that said, I'm not sure whether that's a good or a bad thing. Lynching is an unquestioned evil. But the many monuments to the confederacy help us remember what stories we were telling ourselves about the confederacy and when. According to a brilliant recent piece by Timothy Tyson, those monuments built in North Carolina were overwhelmingly built after 1898, in a time of increasingly virulent, vicious, and violent white supremacy movements and increasing danger for African Americans. In 1898 white North Carolinians violently prevented black citizens from voting and took over the government. That is, the confederate monuments, as Tyson put it, "reflected that moment of white supremacist ascendency as much as they did the Confederate legacy." Salisbury's own confederate monument went up in 1909 as part of this movement.

| I think the fact that the two African American men I spoke with sent me to the tree -- whether the actual tree remains or not -- speaks loudly. I discussed with many people the symbolism of the confederate flag in the post I wrote about Salisbury and its environs, and the divided opinion on the flag and those many confederate monuments affected me. I found it -- and still find it -- stunning that with the overwhelming evidence that the flag stands for slavery, white supremacy, and violence against African Americans, people still manage to believe they are expressing some sort of historical respect by flying it. Anybody who wonders whether the wounds of slavery and the war fought in its defense have healed need only check Salisbury, where the community of those who were lynched still sees the shadow of lynching in the trees that remain. Whether they are the actual trees from which their ancestors hung seems almost beside the point. The point is, tree or not, monuments or not, racism and its legacy are far from historical to African Americans. |

| In fact, when George Hall, the leader of the lynch mob, was arrested, in a horrible irony, Glenn did send soldiers to guard the jail -- though this time to prevent the mob freeing him. Hall was prosecuted and sentenced -- a milestone in North Carolina. The American Law Review, volume 40, cites the Boston Evening Transcript as trumpeting this as "a triumph for law and executive authority, and even more for civilization." Even the previous governor, Charles Aycock, had begun fighting the practice of lynching. Just the same, like Glenn, Aycock was an | |

But back to Rowan County and whether it was founded on hatred -- it does have a rather off-putting legacy of klansmanship. A recent American Experience documentary about the North Carolina Klan in the 1960s focuses on Rowan County and its resident Bob Jones, who led the Klan through its last insurgence, during which the North Carolina chapter became the largest in the nation.

Lest you think even this, fifty long years ago, is long forgiven and forgotten, consider this horrific current event: within the last month, Rowan County swore in as the chair of its Board of Elections one Malcolm Butner, who has a history of overtly racist remarks. Read about them here; I don't want to repeat them. Again, the point: We don't know whether a lynching tree still stands or if one does which one it is. But that the spirit of lynching remains very much alive for North Carolinians? There's no question. I'm glad Susan Sides brought this up. One can never go back to this topic too often. Lawson

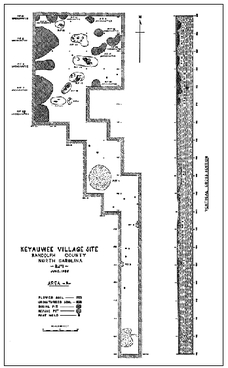

On another topic, the Lost Colony, I discussed a current somewhat crazy theory that the famous Lost Colony vanished in pursuit of a global conspiracy to produce sassafras. I suggested that Lawson would have found the entire question perverse: he took as simple fact that the remainder of the colony had filtered in among the natives and been absorbed. "The English were forced to cohabit with them, for Relief and Conversation; and that in process of Time, they conform'd themselves to the Manners of their Indian Relations," Lawson said.

It turns out that Lawson was exactly right, says Mark Horton, an archaeologist whose work is described by the National Geographic. "The evidence is that they assimilated with the Native Americans but kept their goods," he says, describing broken bowls, a sword hilt, and other evidence found on Hatteras Island. It's a conclusion for which archaeologists have found evidence barely three centuries after Lawson took it as perfectly obvious.

Like I said at the beginning of this piece -- it's always good to go back and check in on what you've already said.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed