"... he assur'd me, that Carolina was the best Country I could go to; and, that there then lay a Ship in the Thames, in which I might have my Passage."

The road not taken...

The road not taken...

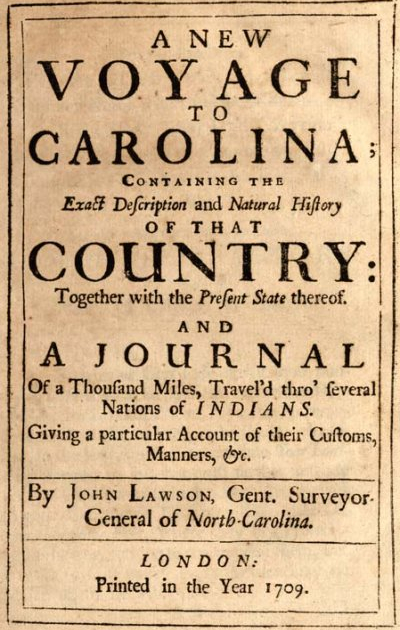

In London in 1700, John Lawson, 25 years old, considered his next move. The son of a Yorkshire doctor and grandnephew of a Vice-Admiral, impressed by the gentlemen of the Royal Society (who met at Gresham College, where Lawson had attended lectures), Lawson was a a young man looking to make his mark on the world.

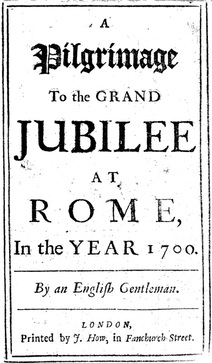

He thought he might as well go to the Grand Jubilee in Rome, a Catholic event held every 25 years drawing pilgrims to Rome. In a Europe still entering the age of enlightenment, the Jubilee was also a World's Fair kind of deal that gave people a good reason to go somewhere and do something. It was a big deal (another English gentleman wrote a book about it, in fact), and so the Jubilee would have been clearly attractive to someone looking for excitement.

But in his own subsequent book Lawson tells us he "accidentally met with a Gentleman who had been Abroad" -- Lawson doesn't give the name. And that gentleman convinced Lawson he was facing the wrong direction. I like to think of the unknown Gentleman saying, "Well, yeah, sure, you can go to the Jubilee, but don't you think Rome is kind of ... I don't know, seventeenth century? The eighteenth century is west -- over in Carolina." Whatever his friend said, Lawson took his advice and headed west instead of east. The history of natural observation in Carolina -- and on North America -- benefited.

He thought he might as well go to the Grand Jubilee in Rome, a Catholic event held every 25 years drawing pilgrims to Rome. In a Europe still entering the age of enlightenment, the Jubilee was also a World's Fair kind of deal that gave people a good reason to go somewhere and do something. It was a big deal (another English gentleman wrote a book about it, in fact), and so the Jubilee would have been clearly attractive to someone looking for excitement.

But in his own subsequent book Lawson tells us he "accidentally met with a Gentleman who had been Abroad" -- Lawson doesn't give the name. And that gentleman convinced Lawson he was facing the wrong direction. I like to think of the unknown Gentleman saying, "Well, yeah, sure, you can go to the Jubilee, but don't you think Rome is kind of ... I don't know, seventeenth century? The eighteenth century is west -- over in Carolina." Whatever his friend said, Lawson took his advice and headed west instead of east. The history of natural observation in Carolina -- and on North America -- benefited.

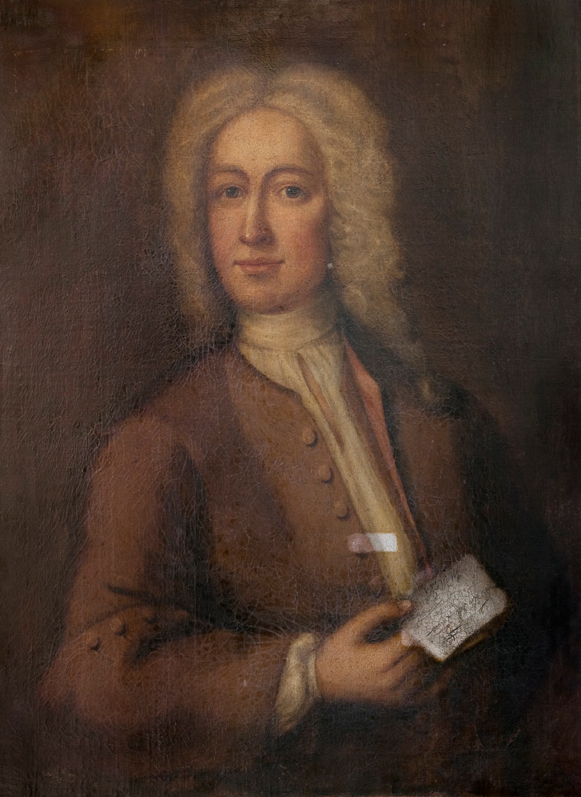

Lawson himself -- we believe. The portrait was purchased in England by a professor at East Carolina University on the possibility of its being Lawson. On one hand, the envelope he's holding says "Sir John Lawson," and Lawson never was knighted. On the other hand, it was painted during Lawson's time by Sir Godfrey Kneller, who painted many of the members of the Royal Society, and Lawson would have had great interest in joining that august company. So it's up in the air. But the portrait is lovely and -- so far -- it's the only image we have.

|

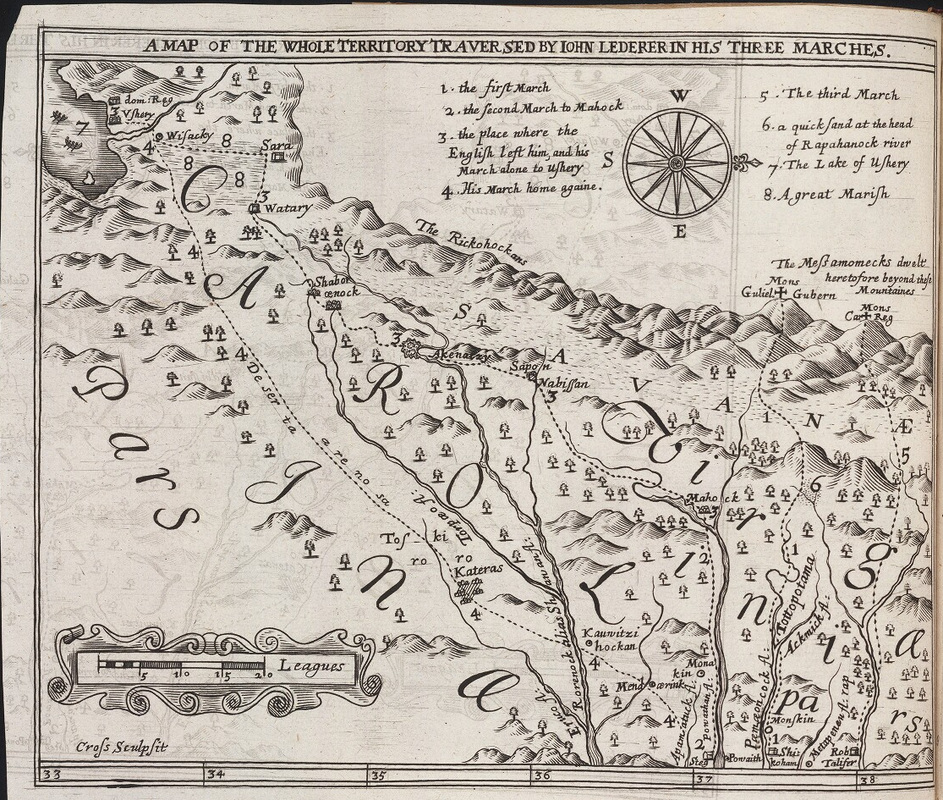

The first thing Lawson did of note was undertake his two-month journey through the Carolina backcountry. He was well-connected back home -- his great-uncle on his father's side was vice-admiral John Lawson, and on his mother's side he was related to the Archbishop of Canterbury -- so it's entirely plausible he was known to the eight Lords Proprietors (supporters of Charles II during the Restoration, rewarded with the vast tracts of land that constituted the Carolina colony) and that they sent him out: "The Lawson boy is looking for employment, and he's in Carolina, which we own. Perhaps we ought to engage him to go for a look-round?" Another possibility is that he was backed by James Moore, on whose boat to Carolina he had received free passage and who soon became not only Lawson's host but governor of the colony. Himself a veteran of an expedition some years before, Moore might have been interested in what lay out there. Then again, Lawson and his friends -- five other colonists -- may have just been itching for something to do.

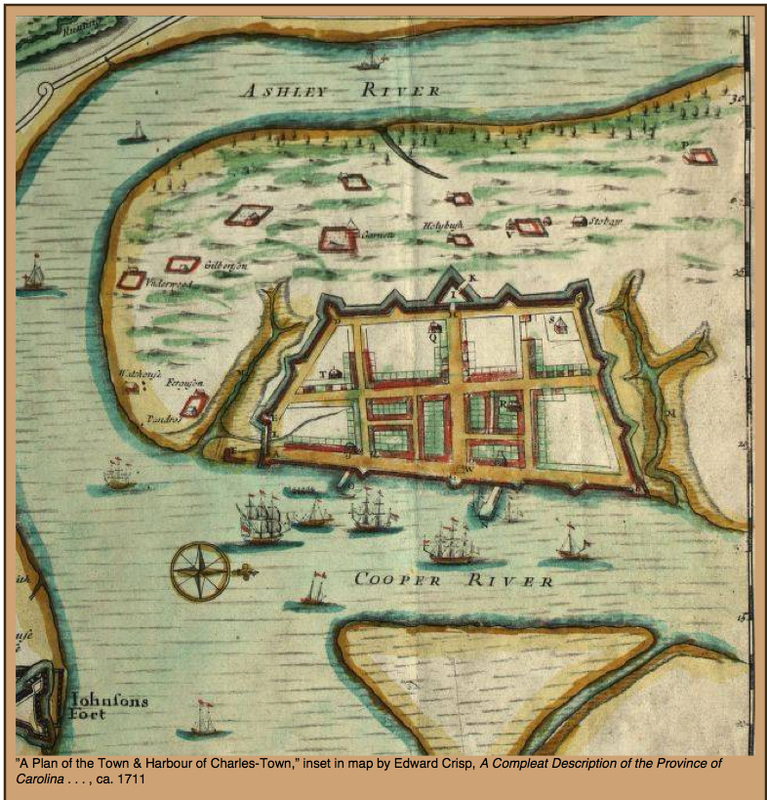

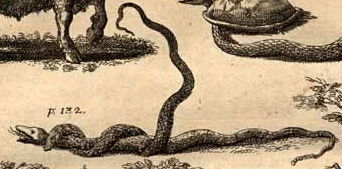

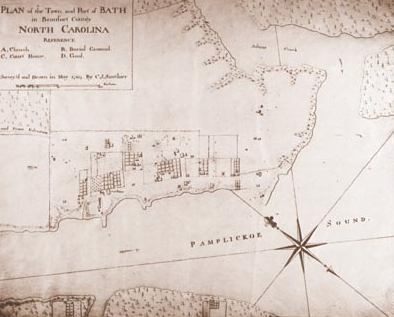

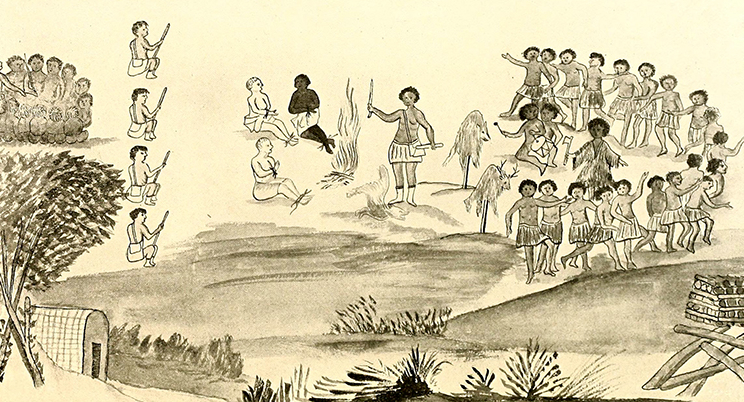

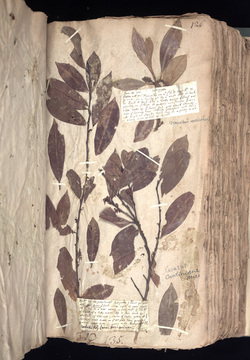

In any case, he arrived in Charleston in mid-1700, and by the end of the year -- the day after his 26th birthday -- he set out on his journey. He ended up in what North Carolinians call "little" Washington, then simply a small British settlement, where he met Richard Smith, a landowner and legislator living at the tip of the Pamlico -- then called Pampticough -- River: "well receiv'd by the Inhabitants and pleas'd with the Goodness of the Country, we all resolv'd to continue," Lawson writes. I should say so. He fell for Smith's daughter, Hannah, and had a child with her, though they never married. In subsequent years Lawson spent his time making continued explorations of North Carolina and the colonies, probably ranging as far north as Philadelphia. In 1706 he was one of the founders of Bath, the first incorporated town in North Carolina, and he laid out its streets. He became clerk of the court and public register of the county of Bath, and in 1708 he became Surveyor General to the colony. In 1709 he returned to London to publish his book, at which point it is believed he had his portrait painted. He returned to the colony the next year, joining forces with Baron Christoph von Graffenried, who was himself helping some Swiss and French Protestant refugees find a place to settle in the New World. Some had settled in Virginia but were not happy, and Lawson helped von Graffenreid plan a town on the outlet of the Neuse River in North Carolina, which came to be known as New Bern. In 1710 and 1711 Lawson continued both his study of North Carolina and his contributions as a colonist. The two roles clashed when, in 1711, he set off with von Graffenreid to seek the source of the Neuse, hoping for a trading route to Virginia. An encounter with the Tuskarora turned ugly, and though von Graffenreid escaped (the Tuskarora appear to have believed he was the governor and would cause more trouble if they killed him), Lawson was killed -- he thus became the first casualty of the Tuskarora War, in which an Indian population fed up with the seizure of their land and the enslavement of their people fought back against the colonists. No prizes for guessing how that one turned out. The Tuscarora War lasted a few years, but the Tuscarora lost. Lawson was never seen again. But the specimens he gathered over his time in the Carolinas were sent to one James Petiver, a London apothecary and citizen scientist. Upon Petiver's death in 1718 his collection was acquired by Hans Sloane, whose 337 volumes of collected plants joined his tens of thousands of other objects. When Sloane died his collection formed the foundation of the British Museum -- a part of which eventually spun off as the Natural History Museum, where Lawson's specimens remain to this day. |

|