This kind of crazy stuff. Pictures of animals, real or imagined, drawn as they would be expected to be by people who had not seen them.

This kind of crazy stuff. Pictures of animals, real or imagined, drawn as they would be expected to be by people who had not seen them. "I look for something that exemplifies the habitat," she says. She considers a droopy mayapple, dismisses the raft of loblollies. "I hate loblollies," she says.

Landin, a biologist, scientific illustrator, and science educator, teaches at NC State University through the biological sciences department, not the art department. That is, she is what I would call a nonfiction artist, and she teaches students to use illustration as a way not just of communicating but of seeing. She has offered a couple hours of her time to do the same for the Lawson Trek, this day including old friend Angie Clemmons, herself an inveterate lover of plants who has taken courses in botanical illustration and is hungry for anything more to learn. We follow Landin like a pair of baby ducks.

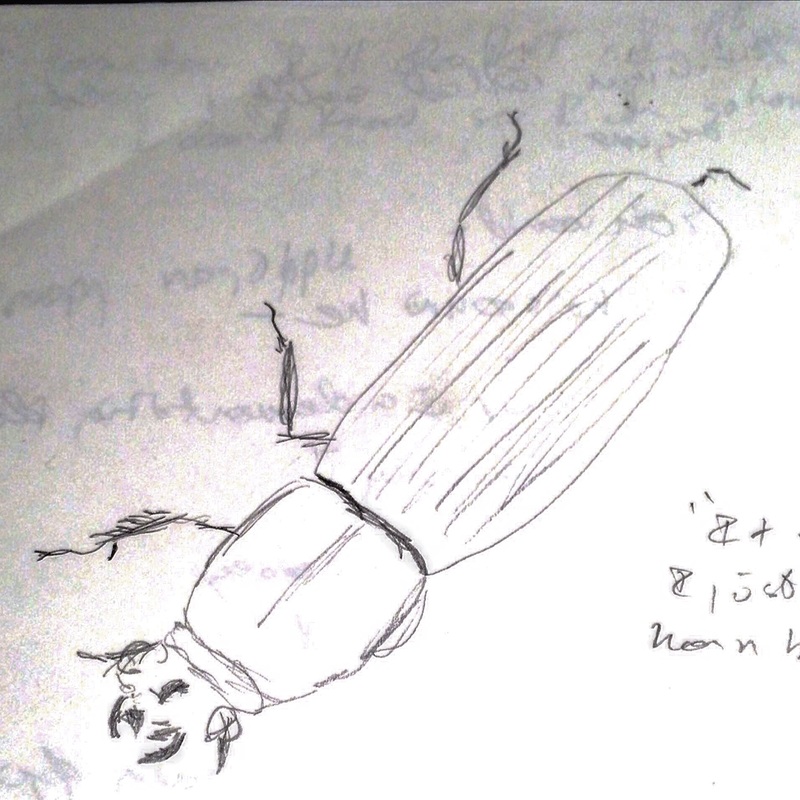

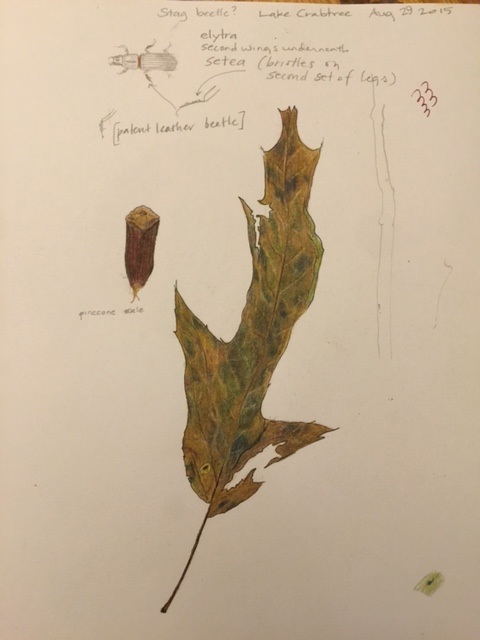

Some grapevines seem like they might answer, or perhaps some bark, or -- wait a minute. "I know what I'm going to draw!" she yells with something approaching glee. She reaches up to the side of a tree and comes down with a smallish black beetle and our day is set. The three of us sit in a circle, place the beetle on an extra drawing pad, and for half an hour or longer we all draw and talk, with Landin leading the way, teaching us to see and represent what is before us.

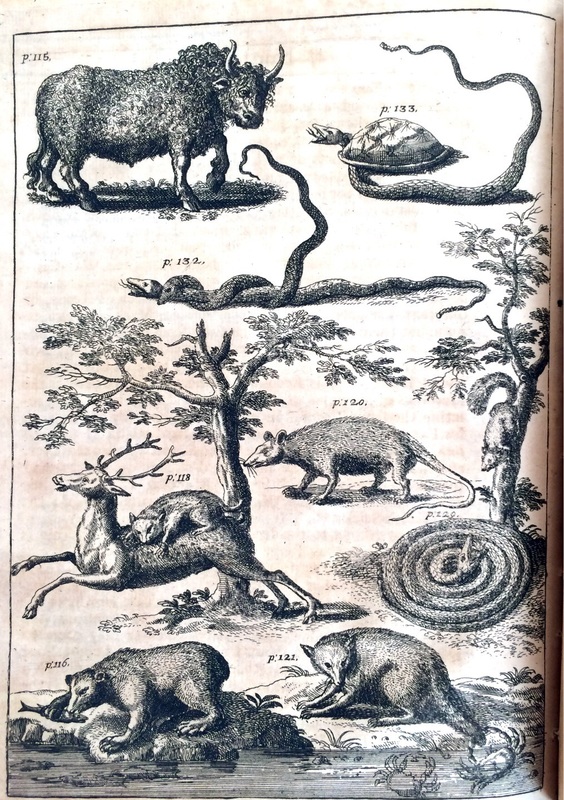

Early in my understanding of Lawson, Landin had helped me to see the crazy illustrations in Lawson's book as a great demonstration of the edginess of Lawson's time. Not edgy in the fatuous sense we use the word now; edgy in the sense that Lawson explored the world when we were at the edge of a new kind of understanding. Read Lawson's A New Voyage to Carolina and you could be reading a modern work of creative nonfiction: Lawson explains where he gets his information, quotes his sources (if sloppily), and uses the powers of observation offered by the nascent scientific revolution.

On the other hand, look at the illustrations in his book -- few though they are -- and, as Landin told me, "they have more in common with medieval bestiaries than scientific illustrations."

| Man, no kidding. It turns out these drawings were made in London, by an engraver, from Lawson's descriptions of what he saw; if Lawson ever drew an image himself, we have no evidence of it. Thus you get a picture of a bison that could be a bison I suppose if you really want it to be one, a bear that might be wearing swim flippers, and a possum that could be one of the R.O.U.S.s from The Princess Bride. The illustrations are evidence that old habits of simply accepting knowledge handed to the observer -- rather than scrupulously observing -- die hard. "He sometimes sees what he expects to see, not what is really there," Landin says of Lawson, and it's a fair criticism; Lawson describes snakes having the power to "charm Squirrels, Hares, Partridges, or any such thing, in such a manner, that they run directly into their Mouths." Landin notes especially that Lawson describes raccoons fishing for crabs with their tails (the illustration shows this!), which though preposterous on its face turns out to be a worldwide myth attributed variously to bears (that's how they lost their tails, natch) and jaguars, monkeys, wolves, and jackals. As Sir Edward Burnett Tylor says in his book Researches into the Early History of Mankind, "it is one of those floating ideas which are taken up as the story-teller's stock in trade, and used where it suits him, but with no particular subordination to fact." |

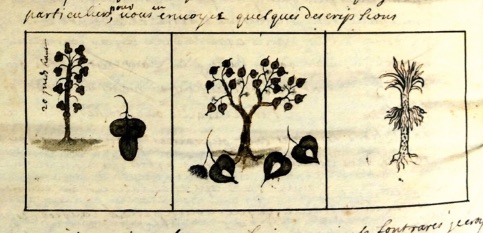

| Crazy pictures drawn mostly from fancy and tall tales accepted as fact -- clearly the scientific revolution was hardly in full flower among Lawson and his ilk. Not that it was far off. Soon after Lawson came Mark Catesby, whose Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, first published in 1731, contains images that could have been drawn by Audubon, that's how modern they appear. Lawson even likely met people among the Huguenots, his journey's early hosts, who produced images far more advanced than his own. My friend Cheves Leland showed me a translation of the letters of one Jean Boyd of Charles Town, from the 1680s, that include drawings that if hardly the equals of Catesby |

| or Audubon at least demonstrate that Boyd knew that the way to draw was to look at a thing for a real long time, and then keep drawing until you get it right. That's what Landin had us doing soon after we sat down. One thing she does is hold out her pencil, vertically and horizontally, like an artist in a cartoon. |

And it's not just observation -- it's understanding. The more you know, the better you draw. Landin points out the beetle's shell-like outer wings, called elytra. "If you know that's a wing, you know it comes out of the thorax, so that's not the abdomen," she said of a segment of the body that both Angie and I thought was the abdomen. "Segmentation," Landin told us, "is really important."

To be sure. In any case, Landin perfectly develops her thoughts on drawing as an element of understanding here, in a post she did on the Scientific American website, and you should read it.

Following Landin, Angie and I were drawing away at our beetles and I at least was thrilled with the way I was representing something far more truly than I would naturally have done -- and I do make sketches in my notebooks, by the way. They'll be better now.

Which, this time, she did. Our pal turns out to be a patent leather beetle or a horned passalus-- odontotaenius disjunctus when she's being formal. "She" because Landin and Angie both just sort of felt she was a female, and who was I to chime in? I had no opinion on the matter.

I have to say I never looked so closely at a beetle in my life -- nor did I ever see one so well. I could show you ten million photos I took, but instead I'll show you our pictures.

Landin told me that Charles Darwin, in a letter to his father, offered this advice to his nephew: "Tell Eyton as far as my experience goes let him study Spanish, French, drawing, and Humboldt." Alexander von Humboldt, of course, was an explorer who, almost exactly a century after Lawson, traveled Central America and described it in scientific terms; Darwin deeply admired him.

Darwin deeply admired drawing, too, and you can see why. Drawing forces your eye to adjust to the reality of the situation -- a bug can't have an indeterminate number of legs when you're drawing it: it has six, and they come out ... just exactly ... here, and then there are these tiny hairs, and on and on. Even a photograph doesn't connect you to a subject the way drawing does.

I'm sorry Lawson didn't draw -- I'd like to see how that would have affected his observations. I'm glad I did, at least this little bit, for it's certainly improved mine.

As for Jennifer Landin, I simply suggest that you go to her blog and study and enjoy it. You didn't get the lesson that Angie and I did, but you'll learn a lot. You may do as you like with French, Spanish, and Humboldt. But take my advice and study Landin.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed