Indian man in match coat, drawn by John White during his 1585 visit to Carolina. The term "match-coat" appears to be a folk etymology from the Algonquian word "mantchcor" or "matchcor." Interesting world, yes? (Image from virtualjamestown.com.)

Indian man in match coat, drawn by John White during his 1585 visit to Carolina. The term "match-coat" appears to be a folk etymology from the Algonquian word "mantchcor" or "matchcor." Interesting world, yes? (Image from virtualjamestown.com.) Their Feather Match-Coats are very pretty, especially some of them, which are made extraordinary charming, containing several pretty Figures wrought in Feathers, making them seem like a fine Flower Silk-Shag; and when new and fresh, they become a Bed very well, instead of a Quilt. Some of another sort are made of Hare, Raccoon, Bever, or Squirrel-Skins, which are very warm. Others again are made of the green Part of the Skin of a Mallard's Head, which they few perfectly well together, their Thread being either the Sinews of a Deer divided very small, or Silk-Grass. When these are finish'd, they look very finely, though they must needs be very troublesome to make. Some of their great Men, as Rulers and such, that have Plenty of Deer Skins by them, will often buy the English-made Coats, which they wear on Festivals and other Days of Visiting. Yet none ever buy any Breeches, saying, that they are too much confin'd in them, which prevents their Speed in running, &c.

He describes the forests and greenery he encounters, in this part of the world noticing an end to the Spanish Moss: "From the Nation of Indians until such Time as you come to the Turkeiruros in North Carolina, you will see no long Moss upon the Trees," and he's exactly right -- we saw Spanish Moss at the beginning of the trek that took us from the High Hills of Santee to the town of Camden, and I haven't seen a strand of it since. He notices that the Indians have a special mark of respect: "At Noon, we stay'd and refresh'd ourselves at a Cabin, where we met with one of their War-Captains, a Man of great Esteem among them. At his Departure from the Cabin, the Man of the House scratch'd this War-Captain on the Shoulder, which is look'd upon as a very great Compliment among them. "

Something about that shoulder scratch appeals to me; Lawson mentions it more than once, and it seems like such a lovely predecessor of the vaguely uncomfortably two-guy sidehug or the performance level shoulders-touching-two-thump handshake that it reminds me: Lawson was a guy just like I am, and the people he met were just people. Just like the people I meet.

That is, Lawson himself when he got to this part of the world was just moving from Indian town to Indian town, and he and his friends only rarely had to sleep out of doors. Not that he always liked the Indian hospitality he received: The People of this Nation are likely tall Persons, and great Pilferers, stealing from us any Thing they could lay their Hands on, though very respectful in giving us what Victuals we wanted," he says of the Wateree-Chickanee Indians he meets not far from here. "We lay in their Cabins all Night, being dark smoaky Holes, as ever I saw any Indians dwell in."

Two friends joined me for the walk into Camden, though I entered Camden alone (described here). But our lodgings were anything but dark smoaky holes. The delightful Joanna Craig of Historic Camden offered us the basement of the historic Kershaw-Cornwallis house, which enabled us to stay bone dry on what was actually a rather rainy weekend. Some nearby Boy Scouts had a somewhat harder time of it.

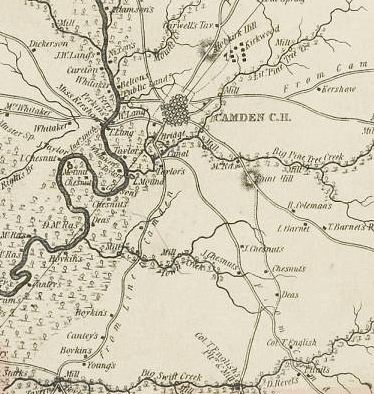

The map of Camden from the 1825 Mills Atlas. You can see how it's just off the Wateree, and that the old road -- surely the one Lawson would have followed up from the Santee. (Image from South Carolina Digital Library -- http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/cdm/search/collection/rma.)

The map of Camden from the 1825 Mills Atlas. You can see how it's just off the Wateree, and that the old road -- surely the one Lawson would have followed up from the Santee. (Image from South Carolina Digital Library -- http://digital.tcl.sc.edu/cdm/search/collection/rma.) So anyhow, into, and through, and past, Camden we went, and in Camden as in Charleston and in McClellanville and in Jamestown and in Horatio we found friends to help us out. I've already mentioned Joanna Craig, who helped and organized and gave us warm and dry sleeping quarters, but at Books on Broad we met owner Laurie Funderburk, who organized a meet-and-greet that was absurdly well attended, the Camdenites coming out and introducing themselves en masse and in all ways making the Lawson Trek feel welcome.

So we wandered. A day into Camden, a day in Camden, then another day north, partway to Lancaster. We visited Boykin on our way into town, where we met Susan Simpson, the broom lady, going about the business of making brooms in a little cabin that had housed slaves in 1740, and saw the mill pond, there since 1792 and the church built six years earlier.

| We saw cemeteries and plantation houses, cotton fields and tree farms, and the usual spate of abandoned houses, including one that took our breath away, not least because as we made our way across a cottonfield to explore it a machine came out to spray the field with nitrogen. It looked like an average machine until it automatically spread its pipes to begin spraying. Michael saw praying mantis; I saw vampire; and Katie, the ecologist, saw, she said, "threat behavior." What we loved most, though, was the town itself. "Horses and history," Joanna said were the themes of Camden, and it's clearly finding a way to keep itself alive with its historical district, arts and antiques dealers, and the nation's second oldest polo field. Camden became a resort town for late-nineteenth-century snowbirds, which gave the horse community its beginning, and it's remained ever since. Walking through town was delightful; this was the first town the Lawson Trek has come through whose primary history did not involve Lawson, explorers, or Indians. Seeing the tidy streets of old houses, many from the years immediately after the revolution, was thrilling and homey and peaceful. | More, we noticed among the porches that most Southern of traditions -- many with ceilings painted haint blue, supposedly to keep ghosts away because the ghosts perceive the blue paint as water and won't cross it. Oh, yeah -- Indians. Of course Camden has an Indian history. It was probably very near the center of the town of Cofitachequi, an Indian polity visited by de Soto, Pardo, and, as late as 1670, by Henry Woodward, the first British colonist of South Carolina. It was gone by the time Lawson came through, when the territory was the southern reach of the Catawba people. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed