Do you remember that I bought an inflatable boat I stupidly hoped to use in our efforts to cross the creeks and streams in the Francis Marion National Forest on the second part of the trek?

Well, whether you remember it or not, I did that, and it became evident that trying to place the boat and then walk to it and then inflate it and so forth was stupid even by my standards, to say nothing of the fact that we would have crossed onto land owned by people other than the National Forest, and those people build fences and have guns.

Anyhow, that boat was still in my trunk. So when after the first day of the third trek hiking partner, Rob Waters, and I found ourselves resident in a cabin in the Santee State Park on Lake Marion, South Carolina, you can imagine what I thought.

I can tell you that after a half-hour of inflating and the construction of oars, the maiden voyage of the S.S. Lawson (maybe the P.R. Lawson, for Paddle Raft?) was a complete success. I paddled out through young cypresses not ten yards from our bacin door and floated into the middle of a little cove and lay on my back, spinning around and trying to catch the eye of Venus, the evening star, with every revolution. It was a lovely moment, though somewhat reduced in satisfaciton by the fact that I was spinning on a lake that by every law of God and man should not be there.

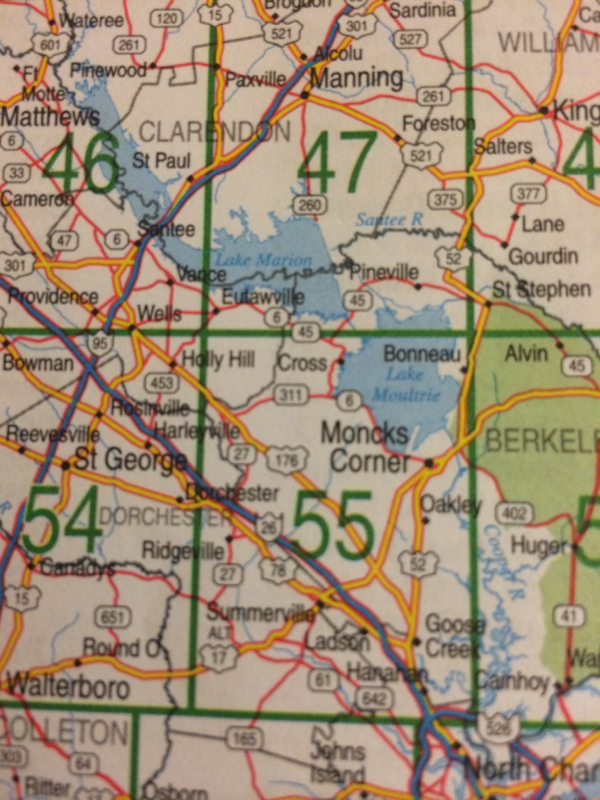

Lake Marion and Lake Moultrie are twin lakes dammed in 1942 by the Army Corps of Engineers for a series of purposes. They feed the Santee Cooper hydropower plant, owned by the State of South Carolina, which helped electrify rural eastern South Carolina, no doubt a good thing. And they provide wonderful recreation, beloved of fisherpersons and the Lawson Trek alike.

Regrettably, as far as the ecology, culture, and landscape of the region goes, they were disastrous.

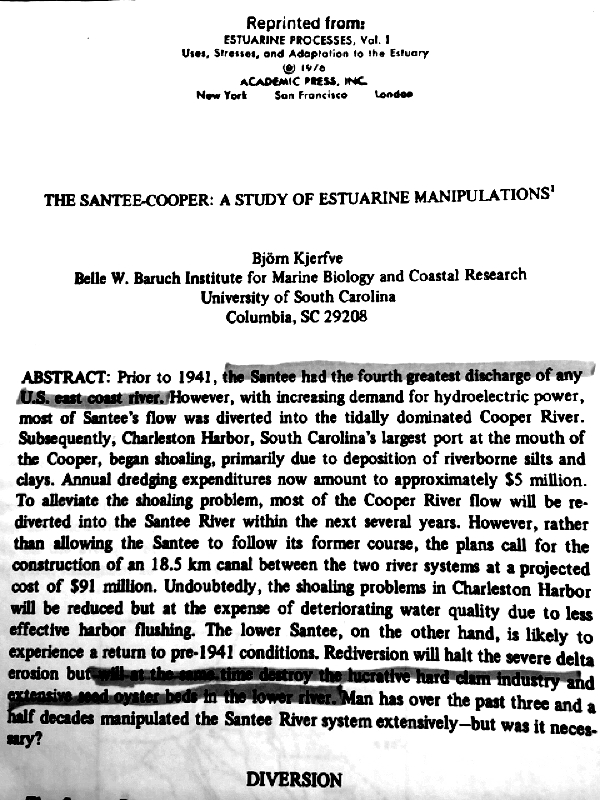

Lawson spoke of the Santee River being more than 36 feet above its usual level when he hiked along its banks. That's of course preposterous -- Lawson's numbers are commonly bizarre exaggeration. But that the Santee was regularly in flood and quite unmanageable there is no doubt. At the time, the Santee had "the fourth greates discharge of any U.S. East Coast river," according to "The Santee-Cooper: A Study of Estuarine Manipulations," which you can find on your shelves in your copy of Estuarine Processes, Vol. 1, 1976.

The Santee was a flooding mess. It overflowed its banks all the time, and the silt it carried barred the river and made it useless as a port. Yet upstream, where it was more navigable, residents a century later saw that it offered access to the farms and settlements of inner Carolina. Meanwhile, the deep Cooper River, which flows by Charleston, petered out not far from the Santee, across a single ridge. In fact, in 1800 the first summit canal (up and over) connected the rivers, allwing river traffic to go up the Cooper, over to the Santee, and deep into Carolina, though the canal languished after the railroads came.

But people couldn't quite give up on fixing what Mother Nature hadn't thought was broken. "The Corps's work is never done," said Bob Morgan, heritage program manager for the Francis Marion National Forest. In the 1930s, along with electrification, planners had the idea that if they combined the two rivers -- the Santee and the Cooper -- and poured them mostely into the Cooper River outlet, they could kind of get a two-for-one. All the extra water would sluice out pollution from the Cooper and keep silt from building up there, and meanwhile the Santee, much smaller, would putter along as a milder, more tractable version of its formes self, unlike the unruly beast that kept Lawson "upon one of these dry Sponts," while most of his compatriates went looking for help by canoe, where "had our Men in the Canoe miscarry'd, we must (in all Probability) have perish'd." (They didn't, by the way.)

Sure! Dam two rivers, combine the flow, and send it the wrong way. What could possibly go wrong?

Almost immediate after the rivers were dammed and combined, the enormous flow carried down the Cooper all the silt that used to fill up the Santee, "with extensive shoaling of Charleston Harbor beginning immediately following diversion," according to the article, which somethow surprised the people who had moved heaven and a hell of a lot of earth to make it do exactly that. And with its vastly diminished flow, the Santee ecosystem shifted from fresh (Lawson describes it as fress all the way to the sea) to salt. Barrier islands began eroding. Trees died. On the positive side, though, the new salt water ecosystem provided a perfect home for clam and oyster beds, and a significant industry grew up.

What's that Bob Morgan said? Oh, yeah. By the late 1970s the Corps decided to unfix what was never un ... whatever. It decided most of the water needed to go back down the Santee. Cool enough, but instead of just opening the hold on the Lake Marion dam bigger, it dug an entirely new canal, called -- I love this -- the Cooper River Rediversion Project -- and the Corps's page about it crows that it saves $14 million per year in dredging costs in Charleston Harbor, which being honest, is exactly like the money a protection racket saves you in avoiding arson costs. Oh, yeah -- the renewed freshwater flow destroyed the clam and oyster industry that had grown up, too, as the freshwater moved further downstream again towards the sea. Our friend and guide (and clam farmer) Eddie Stroman told us about that, and he lived it.

No disrespect to the Corps -- you win some, you lose some.

But according to author Richard Porcher, even the ecological catastrophe was hardly the worst of it.

"It was a cultural and ecological abomination," he says. You get that cultural came first, right? He's involved in a project right now, trying to document the history of the people, mostly African American, who lived on the land before it was drowned, especially beneath Lake Moultrie. Ecologically, he compares the area beneath Moultrie to the famous ACE Basin, a portion of South Carolina near Beaufort protected from development and considered a natural treasure. "This would have been the equivalent," he says. "You lost 150,000 acres of longleaf pineland, riverland, creek land.

"But the main thing is the history of the people was not recorded."

He recites place names like Raccoon Hills and Hog Swamp, the names all that's left of places that, because of the poverty and excluded nature of their inhabitants, never even made it onto the map. "Santee Cooper did not document one African American settlement, not one interview, not one photograph," Porcher says. Which, honestly, we've heard before. Our host on our previous segment, Jean Guerry, told us of her daddy driving her through the area so that she could see what was going to be lost. Homes and plantations and other buildings were disassembled and sold for parts.

So, anyhow, here we are: floating in inflatable boats and staying in a pleasant cabin on an absolutely lovely lake. Because of which the Santee River that Lawson followed -- rising and falling according to nature's call -- is gone for good. And so is most of the history of the poor people who lived here, though Porcher hopes to resolve that.

You win some you lose some.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed