| One awesome thing about undertaking a project like retracing the route taken by someone like Lawson is that amazing people almost instantly begin flinging themselves at you out of the ether. Consider Dale Loberger. A geographic information system (GIS) specialist, Loberger works with Bradshaw Consulting in South Carolina, using GIS to improve people's lives and their understanding of their world -- through systems that connect information with maps (it's not just a fire hydrant; it's a fire hydrant last painted in 2007 and last maintained in 2012; it's not just an address, it's an address with a 17 percent likelihood of generating a 911 call within the next year). That U.S. map showing which NFL team each county prefers? That's a GIS map. |

The Great Wagon Road drawn on a perfectly vague map from 1755

The Great Wagon Road drawn on a perfectly vague map from 1755 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Loberger said, something like the Great Wagon Road "was less a name than a description." The Road referred to various ways leading, in general, from Philadelphia in the northeast down into Georgia, generally following the eastern edge of the Appalachians -- and, not coincidentally, the Trading Path, which existed before the Wagon Road, and the animal paths that probably existed before that. Roads were moving-around things in those days before significant paving -- they moved to accommodate new towns, to avoid swamps or ditches, to solve the needs of new kinds of wagons.

More, he says, the maps were meant to be nothing like we think of maps now, and returning to old maps trying to get specific pathways from them is a game of "teasing information from maps never designed to give that information." Speaking in an 18th century museum house in Raleigh, Loberger used a highly 21st-century ArcGIS Explorer* presentation while wearing his 19th-century surveying garb (don't worry, he assured me -- he has plenty of eighteenth-century gear more appropriate to Lawson's time). To understand those maps Loberger learned to survey. Most educated men of the 18th century would have learned surveying -- less as a job skill than as a way to truly learn math and computation. (Seriously, every educated man. Surveyor joke: What does a surveyor say when looking at Mt. Rushmore? "Well, there's three surveyors, but who's that other guy?" Teddy Roosevelt was the non-surveying president.) And surely Lawson knew surveying -- in 1708 he ended up as the Surveyor-General of the Carolina colony. Surveying in those days, Loberger has learned, often focused to a level of detail no greater than a single link in a surveyor's chain (7.92 inches) or even a single surveyor's pole (16.5 feet). Once you realize that the original surveyors figured that three person-lengths ("Smoots," to MIT students) was close enough, you're going to feel a little foolish trying to apply your phone's calculation of your position in degrees to 14 decimal points.

But not so fast. Loberger didn't give up. "These are not documents of truth," he says of old maps. But "they're documents full of secrets." He reasoned that the roads drawn on early maps were closer to legend images, like picnic tables for parks or big question marks for information centers, than actual representations of specific paths: all they did was say, "Charlotte and Salisbury are connected by road," not "the road from Charolotte to Salisbury looks like this." Just the same, the paths had to exist -- and if they did, they'd do what roads always did. They'd go the easiest way possible from point of interest to point of interest -- village, watering hole, mountain pass -- following the most sensible path: choosing solid places where you can easily ford a creek, following dry ridges where you can avoid insects and moisture plus not constantly climb and descend, traversing open land where you didn't have to wrestle through underbrush.

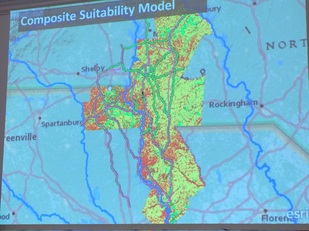

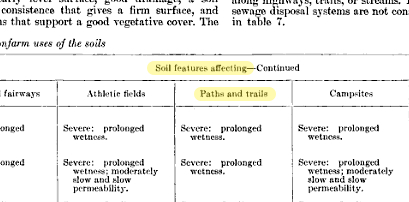

| So Loberger turned to modern maps. The Natural Resources Conservation Service, he saw, rates soils for various purposes -- including limitations on utility for paths and trails. He realized that hydric soils -- those formed under conditions of wetness -- would make for bad roads, given that the wet conditions may remain. Soils indicative of thick undergrowth during formation would give the same hint: why would people -- or animals -- wrestle |

Loberger's composite suitability model

Loberger's composite suitability model Hoping to come within a mile of somewhere a road's original travelers would have walked, he describes a road he looked for near Charlotte. He found a road that he thought was likely the exact spot and felt certain that, given the uncertainties of old surveying methods and the assumptions of his model, he was probably in the ballpark, within 15 or 16 miles of Charlotte. After he once explained what he had done, someone approached him with a question. "Would you like to see one of the markers?" And took Loberger to a granite stone, marked "XV To C." Loberger wasn't sure whether a Roman "I" followed the "V," but the guy assured him. "That's 15," he said. "I know where 16 is" -- it had been used in a fence.

| If I had to begin looking for Lawson's trail to bring me finally to Loberger? It's already worth it. Loberger will join us on the trail, probably around Charlotte, and he'll not only help us know exactly where Lawson would have gone but teach us to use the surveying tools that Lawson would have used. This one is called a Gunter scale, named after surveyor Edmund Gunter, who invented it as a sort of pre-slide rule, using logarithmic scales to simplify calculations.Of course Gunter had to become professor of astronomy at Gresham College, where Lawson took classes, because once you start looking for connections that's how it always happens. He was there long before Lawson was, but still. Loberger has tons more cool stuff and ideas, and he'll tell us all about them when he joins us on the trek, probably sometime in the winter or spring. *Oops. I originally called this a PowerPoint. My bad. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed