So when I could no longer ignore the fact that Lawson mentions barbecue, I went looking for the story of barbecue, that favored food of the South -- and, it turns out, the Indians.

As early as his visit with the Santee Indians, only a couple weeks into his trek, Lawson describes how they Santee "made us very welcome with fat barbacu'd Venison, which the Woman of the Cabin took and tore in Pieces with her Teeth, so put it into a Mortar, beating it to Rags, afterwards stew[ing] it with Water, and other Ingredients, which makes a very savoury Dish." You want my opinion? That sounds so exactly like the pulled-apart pig or beef we eat today that you could put it in a cookbook.

Dan the Pig Man could not agree more. A onetime journalist and longtime lover of barbecue, he now runs a food truck and catering company and met with me in front of his headquarters off a gravel road near York, SC, built in what you might call the Rural-Palatial style.

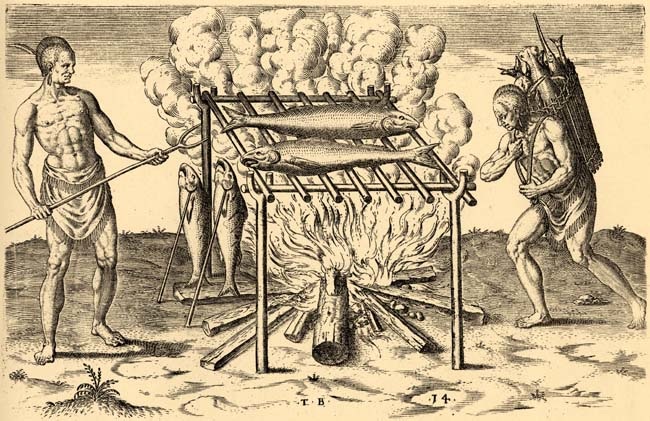

Barbacoa was the Caribbean word for the stilt platforms and grids of green sticks used for cooking and especially smoking the food, which rendered it safe for storage by dehydrating it and killing bacteria. Plus it made it taste good. "I talk about barbecue coming up with the pirates along the East Coast," Dan says, and it may be so. "The tradition wafted inland like hickory smoke."

And as much as Dan loves Carolina barbecue and its many approaches, he knows that in reality it's that simplest of things: meat + fire + smoke + time = good eating. "The great food cultures of the world start with poor people getting the poor cuts of mean," he says. "How do you tenderize it? What do poor people have a lot of? Time, wood, smoke.

"When I grew up in Charlotte in the 50s and 60s, barbecue was not an urban white thing at all," he says. It was something you went out to the poorer quarters for, and bought there. What's more, if you get right down to it, "It's meat and fire. It's animals and lightning. Barbecue started when the first wooly mammoth fell in the campfire."

Still, he sees Lawson as playing an important role with barbecue like he does with so much of Carolina and Southeastern culture. "The significance of Lawson is he didn't hang around the coast. He went into the backwoods." He witnessed all the ways Indian cultures barbecued their meat, and "I would argue that it was Lawson who first took that tradition back over the Atlantic." I didn't see a trace of barbecue when I visited Lawson's botanical specimens at the Museum of Natural History in London, but Lawson did return to England in 1709 and stay for a year. I expect he ate with some tastemakers, and if he didn't carry the message, surely his book did when it came out that year.

You can bet we'll be arguing about barbecue in the Carolinas for at least another 300 years. But as ever when it comes to the Carolinas, Lawson helped set the terms of the discussion.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed