The intersection of Long Lane and Aldersgate Streets doesn't quite radiate historic charm. Oh well.

The intersection of Long Lane and Aldersgate Streets doesn't quite radiate historic charm. Oh well. Hans Sloane, whose collection founded the British Museum, was a physician who had apprenticed as an apothecary. Petiver, who had dozens of corresponding collectors and whose contribution made up more than a third of Sloane's final collection, was an apothecary, "at the White Cross, near Long Lane in Aldersgate Street." The apothecary was where people went for help with their health, for information on their world.

You may have already sort of known this, but once you start following the flow of information -- and botanical specimens -- in the old days, it amazes you. I went to the Natural History Museum to see the results of the flow of information through Petiver and Sloane's apothecary habits, and I went to Long Lane and Aldersgate Street in London to see where Petiver's apothecary once stood. It's a pretty boring intersection now.

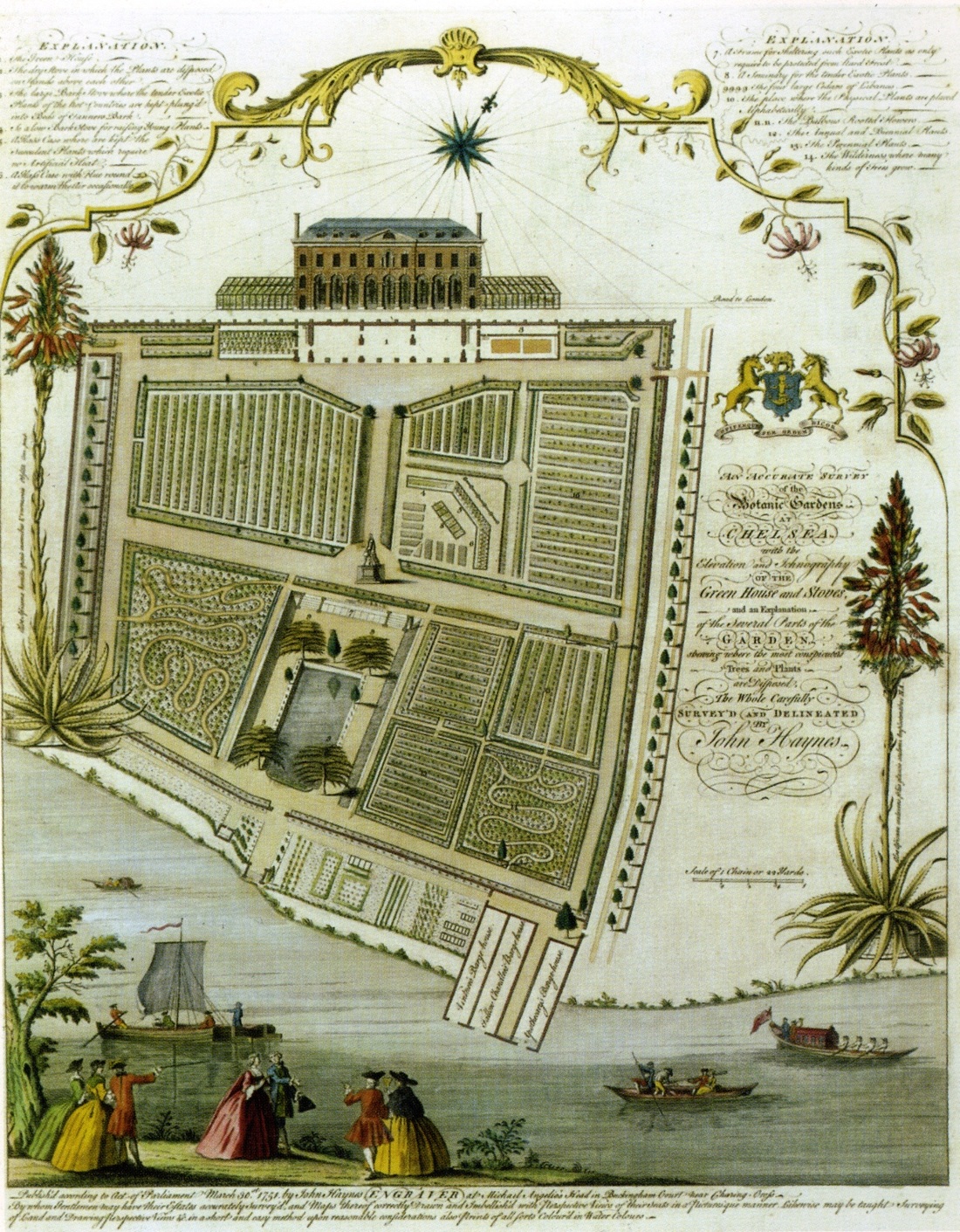

On the other hand, I also traveled to the Chelsea Physic Garden, right on the banks of the Thames. There I found myself in a place I would never have known of had I not traced up from Lawson to Petiver and Sloane. Founded in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, the Chelsea Physic Garden is, besides the Oxford Botanical Garden, founded in 1621, the oldest botanical garden in England. Its guide describes it as "at its peak, during the 1700s, the most important centre for plant exchange on the planet."

So, kinda cool place.

Sir Hans Sloane surveys the Chelsea Physic Garden, where he apprenticed and began the lifelong passion for collecting and scientific observation that culminated in the founding of the British Museum. As the passage from Shakespeare below demonstrates, apothecaries were known for their interest in all things scientific, not merely the medicinal plants that formed the greater part of medicine in the 1600s and 1700s. I do remember an apothecary,— And hereabouts he dwells,—which late I noted In tatter'd weeds, with overwhelming brows, Culling of simples; meager were his looks, Sharp misery had worn him to the bones; And in his needy shop a tortoise hung, An alligator stuff'd, and other skins Of ill-shaped fishes; and about his shelves A beggarly account of empty boxes, Green earthen pots, bladders and musty seeds, Remnants of packthread and old cakes of roses, Were thinly scatter'd, to make up a show. -- Romeo and Juliet, V, i, 37-48. | Spread out over four acres along the Thames, the garden not only grew where gardens and markets had flourished since the time of Henry VIII but offered easy access to the river, the safest and most convenient way for the Apothecaries to travel, receive specimens from all over the world, and to store "the gaily painted barge they used for royal pageants for their celebrated 'herborising' expeditions," according to the Garden's own history. It struggled in its early decades but in 1712 was purchased, along with the nearby Manor of Chelsea, by Sloane (I'll explain how he got the money later), which explains why you come to the garden down Lower Sloane Street, from the Sloane Square tube station. The garden contains sections dedicated to medicinal plants, useful plants, and the oldest rock garden in Europe. Signs and guides provide explanations of the uses of such plants as hyssop (helps the ears) and goldenrod (helps pass bladder stones), and descriptions of the first herbal guides, published in the 1500s. A statue of Sloane stands at the center, but you follow paths and lawns to history beds (showing off species collected by famous head gardeners) and systematic order beds. There are some of Europe's first greenhouses, too, as well -- of course -- as a place to have tea. As delightful as the garden was, though, it helped tie together the stories of Lawson, Petiver, and Sloane. That is, consider the lines at left from Shakespeare, painting an apothecary in his mysterious lair full of animal skins; add in special access to this sort of secret garden; then add in the statue, the correspondence, and the books full of pressed flowers and jars full of faunal specimens preserved in spirits I saw at the Natural History Museum. Put them together and could you even think of a cooler job? Apothecaries were scientists and arcanists, naturalists and archivists, physicians and medical researchers. They worked in libraries full of leather books and laboratories full of beakers and decoctions and freaky stuff preserved in spirits. And when as Europe explored the world anybody found anything sufficiently weird, the explorer sent it back to the apothecaries. |

| In what way does this not describe the coolest job in history? Sloane's own story makes the case. Well-enough known to enlightenment luminaries like philosopher John Locke and naturalist John Ray to be a member of the Royal Society in 1685, Sloane traveled to Jamaica as a court physician; while there he encountered a local combination of water and chocolate that he called "nauseaous." An apothecary doesn't leave poor enough alone. He discovered that by adding milk he made the beverage delightful and thereby created what we call hot chocolate, which took England by storm. (ADDITION, 7-13-15: I am told by an extremely reliable source that this story is regarded by those who know things as apocryphal. Sloane made his money by marrying a sugar widow and by being a doctor. Who knew?) |

Specimens in jars on display in the Darwin Centre of the Natural History Museum. Images used by permission of the Natural History Museum.

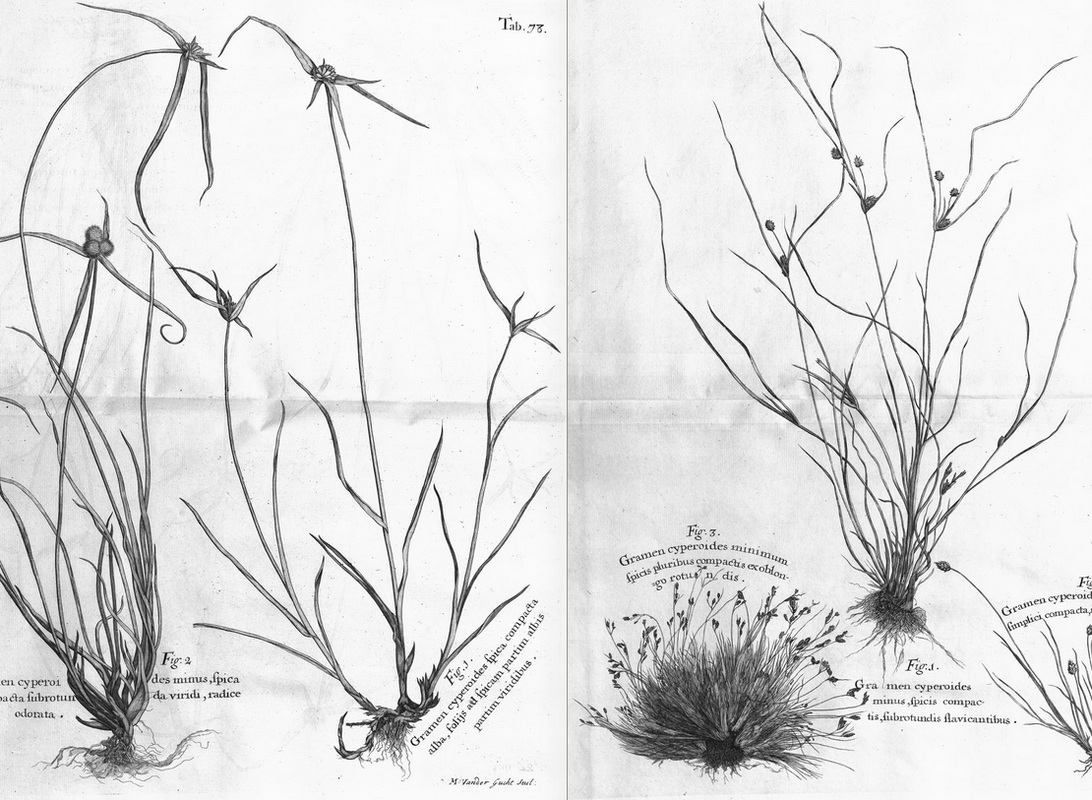

Specimens in jars on display in the Darwin Centre of the Natural History Museum. Images used by permission of the Natural History Museum. Sloane wrote up his travels in Jamaica, in a 1696 catalog and a richly illustrated full Natural History published in 1707 and 1725.

But again -- that whole notion of collecting, of bringing to you the wonders of the age, of learning and displaying the secrets of nature, was the big takeaway for me. Sloane's house was visited as something of an invitation-only museum in his lifetime, and some of those specimens remain on display in the Darwin Centre at the Natural History Museum, spookily floating in jars.

And I couldn't help noticing that we've retained that adoration of the apothecary as a place of mystery and wonder as I visited the rest of London. If you go to the Making of Harry Potter Studio Tour (and you should!), you'll get to walk down the original set for the famous Diagon Alley. And there, among the quidditch shops and wand shops, among all the fancy and wonder, you'll find two examples of only one kind of business: Apothecaries, with Mr. Mulpepper competing -- right next door! -- with Slug & Jiggers, both with windows full of jars, potions, and specimens that could have come right from the Darwin Centre. We went to the Museum of London as well (also recommended!), where the Victorian Walk allows you to wander a London street from the late nineteenth century.

Yep. Apothecary. Turns out that once stuff is cool, it just stays cool. Ancient specimens, animals in spirit, a garden full of the plants of the world -- and hot chocolate.

Lawson was onto something.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed