Sorry.

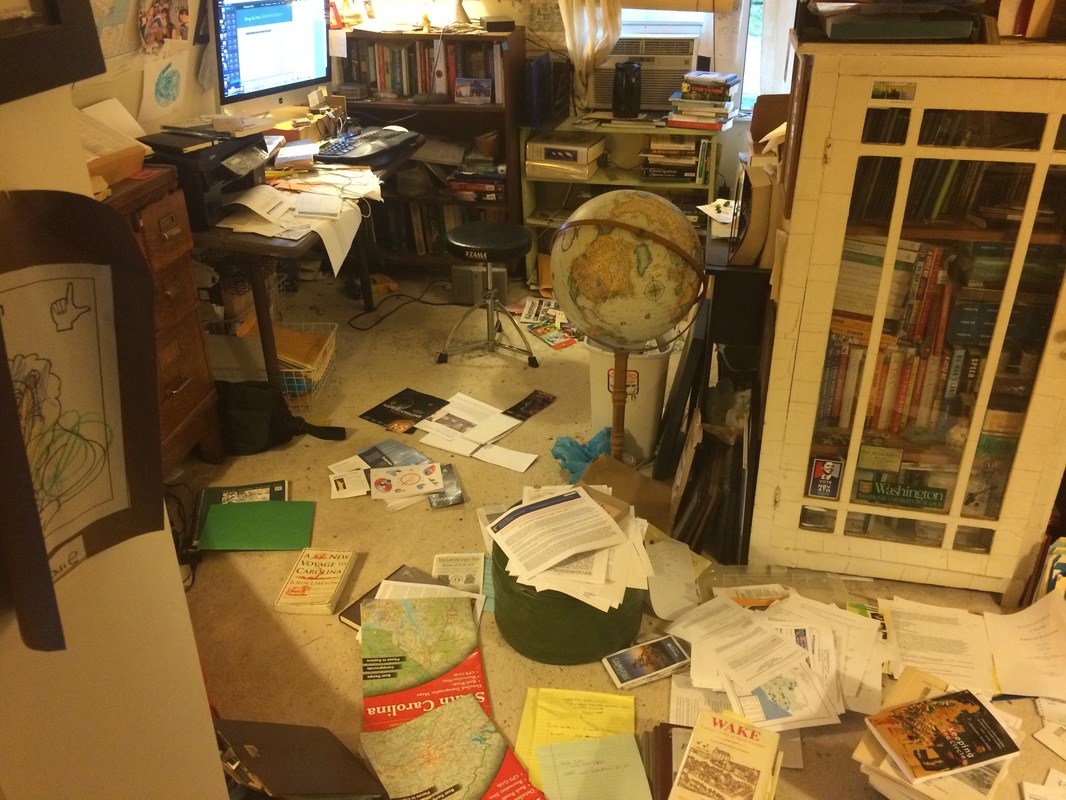

The laundry -- my main indoor daily chore -- has become a thing of madness, though I am working my way back in. Fortunately we had a dry summer so the outdoor chores I was failing to do in some ways went unnoticed. In my other chores I have mostly been derelict, with the expected result that I have returned to a houseful of people who at the very least have grown used to doing without me and more often cannot fail to think "dereliction of duty" when they notice I am around.

A year ago we had a cat. Now instead we have two birds. One of the three fish, if he has not died, is floating rather more substantially with the current than was once his habit, and he is significantly less wedded to the notion of the top being up just all the time.

Both license plates have stickers, but it took a firm reminder from someone with a very fancy car to get there.

All of which is to say, I didn't have to shoot an arrow through a dozen axes and kill off most of the neighborhood, but coming home is never easy.

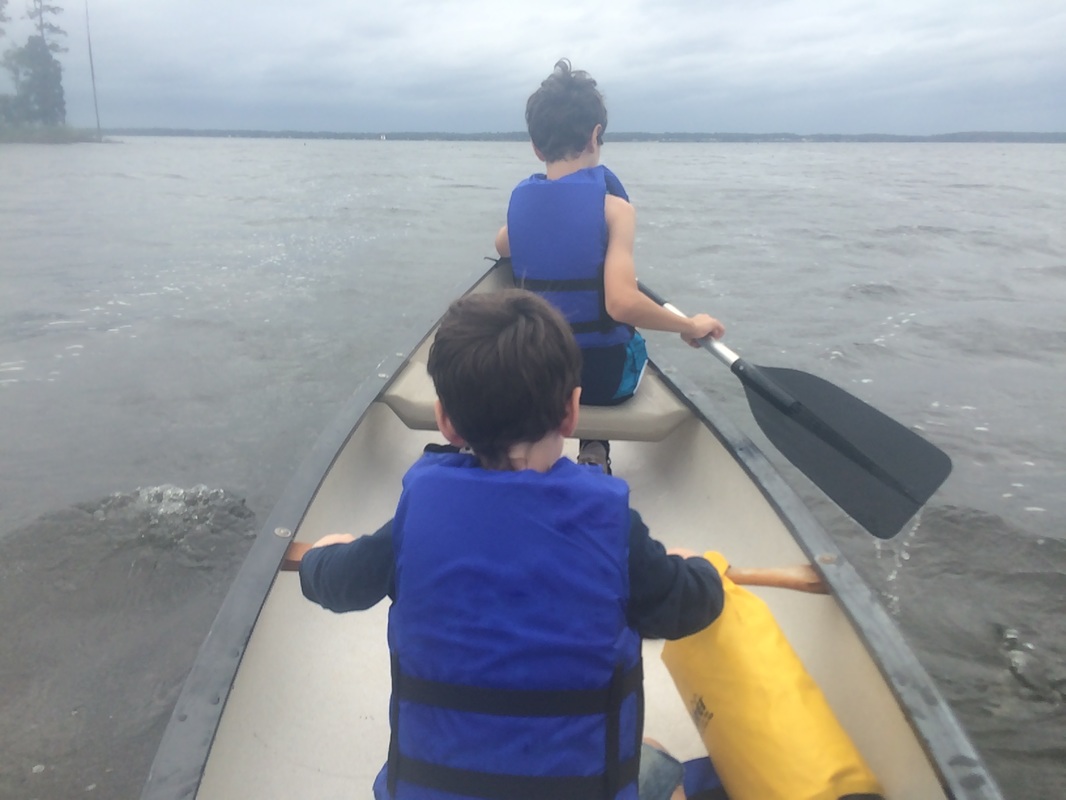

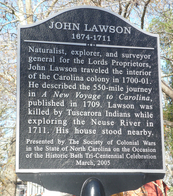

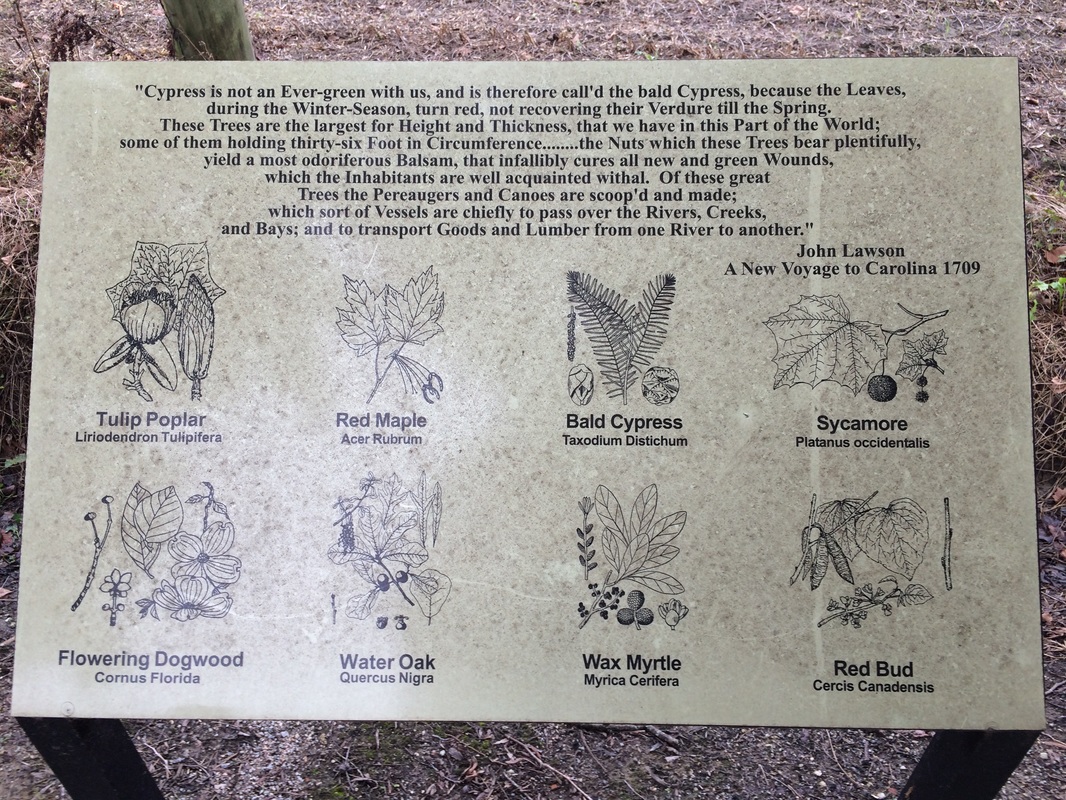

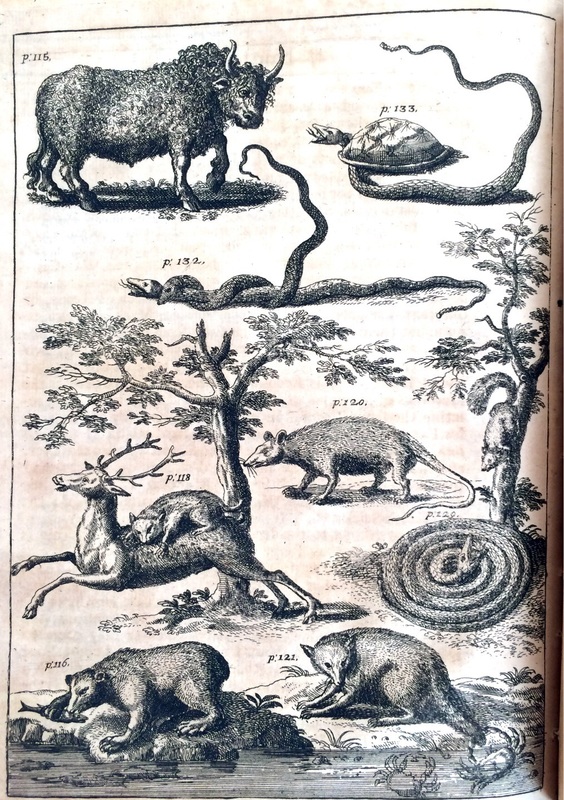

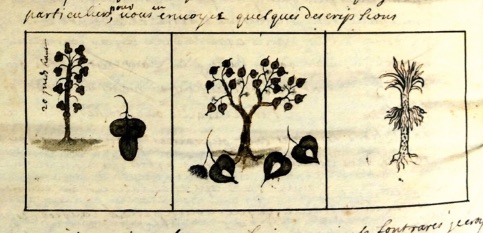

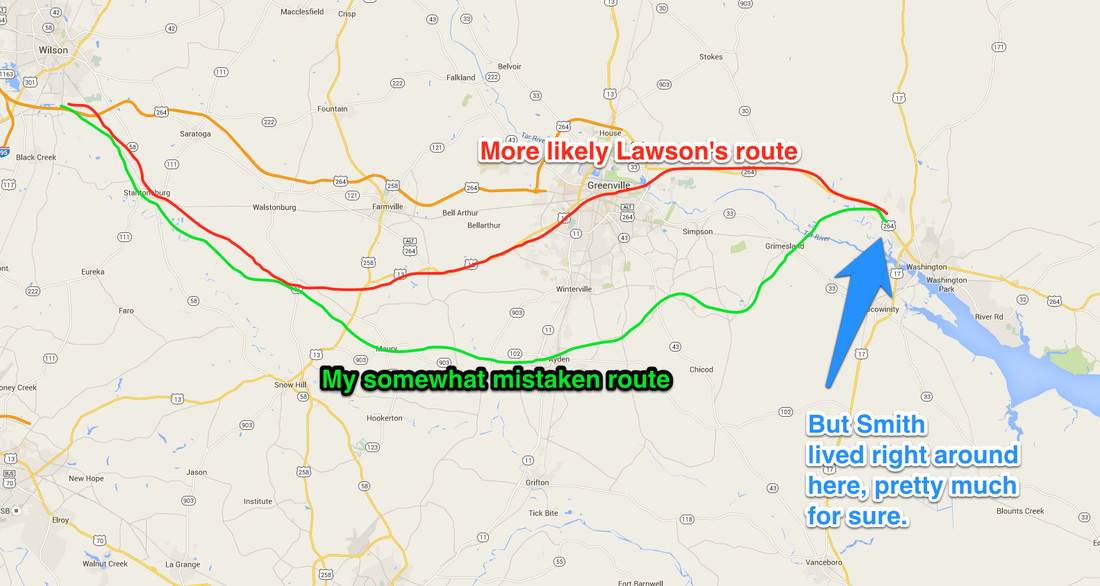

Lawson dropped his pack and there he was, instantly falling for the young Hannah Smith, daughter of settler Richard Smith. Lawson had the benefit of being utterly unconnected in North America and thus able to walk into the bush in December and walk back out in February, saying, "Okay, I guess I'll live here now," and then just living there.

I'm not saying I envy him. I'm just saying that was his world. And if my world is somewhat less adventurous, it has its rewards.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed